Skin-sparing mastectomy

Introduction

Our post-mastectomy breast reconstruction experience has taught us that it is necessary to accurately define surgical sequelae to prevent problems in reconstruction and to design it according to the individual characteristics of each patient. Techniques involving autologous procedures such as dorsi flap, TRAM flap (TF), DIEP flap, and lipotransfer, among others, and heterologous procedures such as tissue expanders and prosthetic devices have proven to be excellent for the restoration of breast volume. These techniques were introduced in the 1980s (1,2), when delayed breast reconstruction was popular, and outcomes improved with the increased experience of involved surgeons and advances in the prosthetic materials used for these procedures.

Incorporating immediate reconstruction as an oncologically safe surgical procedure (3-5) not only improved patients’ physical and psychological perspectives but also forced surgeons to refine their techniques. Skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) was later introduced to optimize the cosmetic outcomes of smaller incisions and to preserve breast anatomy. As a result of these conceptual changes, the following new questions arose:

- Does immediate reconstruction complicate or modify the course of the disease?

- In cases where the surgeon can select the incision location and length, can this procedure improve the outcome of reconstruction?

- Does conserving more skin and mammary structure have a direct impact on the final aesthetic result?

- Do aesthetic and conservative incisions have implications for the control of local and/or distant disease?

For the second time since the advent of radical conservative surgery, its applicability in the surgical treatment of breast cancer has been questioned. In this article, we discuss the origin of mastectomy with preserved skin, its fundamental aspects, indications, technique, complications, oncological safety, and finally cosmetic outcomes.

Overview

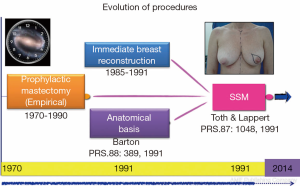

In June 1991, Toth and Lappert (6) first used the term “skin-sparing mastectomy” for immediate reconstruction, and around the same time, Kroll et al. (7) published the MD Anderson experience in 100 cases using the same technique. These reports led to the start of an interesting discussion on the improvement of cosmetic results and parallel doubts regarding local disease control.

But this story actually begins here, but before and serendipity. Barton et al. (8) has a job where I wanted to test the hypothesis insecurity of prophylactic mastectomies [retaining skin and nipple areola complex (NAC)] with the assumption that these glandular residue left over that year. A comparison with conventional cancer mastectomies (without skin sparing) performed by trained surgeons of the same institution revealed persistent gland flaps, sub-mammary furrow, and axillary extension, taking these samples to independent surgeons who conducted the primary resection. Contrary to expectations, the rates of glandular residue were similar between the two groups (21% with therapeutic mastectomy versus 22% with prophylactic surgery), which raised questions as to the value of prophylactic surgery and the effectiveness of conventional radical methods. This experience, in parallel with the first publication on immediate breast reconstruction mastectomies, marked the start of the SSM era, and a new horizon had been set for good cosmetic results and oncological safety (Figure 1).

With the discovery of mutations to BCRA1 (9) and BRCA2 (10) oncogenes in 1994 and 1995, respectively, and their association with high breast cancer risk, new preventative measures were advocated for high-risk patients. Stefanek et al. (11) redefined the term “risk reduction surgery” for prophylactic mastectomies, which was the start of another new chapter in breast cancer surgery. First, preventative and therapeutic indications were postulated in an attempt to not only retain the skin but also the NAC (12,13). This therapeutic approach is the subject of ongoing controversy, as indicated in previously published research protocols (Figure 2).

Definitions and classifications

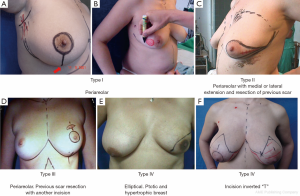

SSM is defined as a simple or radical surgery with modified minimal incisions that retain the widest possible coverage and sub-cutaneous breast groove but dry the NAC, flaws of previous biopsies and/or scarring caused by diagnostic percutaneous biopsies. Access to the armpit for a possible sentinel-node biopsy or axillary dissection is obtained through the same incision. An additional incision may be necessary to perform the reconstructive procedure (e.g., microsurgical axillary anastomosis). SSM is classified into the following five types (6,14,15), as shown in Figure 3:

- NAC peri-areolar resection or losangic resection of breast skin;

- Resection of the NAC with medial or lateral extension and previous biopsy scar resection;

- NAC peri-areolar resection and incision for resection of previous biopsy scar;

- Elliptical, wider resection of skin including the NAC aimed at reducing ptosis (indicated in ptotic and hypertrophic breasts);

- Resection of skin and CAP with inverted T pattern (indicated in ptotic and hypertrophic breasts).

Indications

SSM can be performed in patients requiring mastectomy for: ductal carcinoma in situ; stage I-II infiltrating breast carcinomas [the Union for International Cancer Control and American Joint Committee on Cancer (UICC-AJCC)], and in much selected cases, stage III (16); and local recurrences (LRs) after conservative treatment, when the skin has a slight heating sequel (17). Contraindications for SSM include: inflammatory carcinomas, locally advanced carcinomas, and smoking (relative contraindication).

Surgical technique

For good outcomes with a low complication rate, it is necessary to consider the fundamental aspects of this technique. First, the incision must be designed depending on the presence or absence of scars after excisional biopsy or puncture, as well as breast volume and ptosis (Figure 3).

In type I SSM, a 5-mm incision is made from the edge of the NAC with its surroundings marked, and a second transverse axillary incision can be made for axillary dissection or a possible microsurgical anastomosis. Some situations may require the peri-areolar incision to be extended into the armpit or to the 6 o’clock position to facilitate performance of the reconstruction technique. In type II, contemplates inclusion in NAC incision and scar prior continuity being designed in particular according to the present scar. In type III SSM, the incisions for NAC resection and previous scar are designed separately, to allow a “bridge” between both cutaneous non-small margins and avoid possible loss of vitality. Types IV and V are for ptotic breasts, when correction of the asymmetry of the opposite breast is considered, and can be used with elliptical skin resection or incision techniques such as the inverted “T” resection performed bilaterally for the NAC.

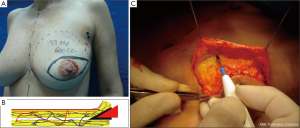

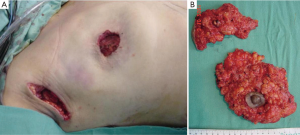

The dissected mastectomy flaps require a more detailed explanation as they are the key factors in this surgery from the oncological as well as postoperative vitality perspectives. The dissection must be meticulous, and the flaps must be of uniform thickness to avoid trauma with spacers. Very thin flaps do not increase oncological safety and are associated with a higher incidence of skin necrosis (Figure 4) (18).

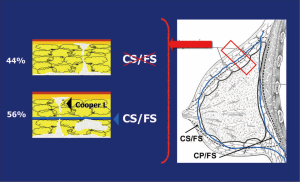

Previous anatomical studies have shown that only 56% of patients have superficial layer of the superficial fascia, which facilitates dissection, but the remaining 44% is difficult to perform this surgical technique. Moreover, in both cases, there may be a mammary gland near the dermis, making it virtually impossible to complete removal of the breast tissue without compromising the vitality of the flaps (19) (Figure 5).

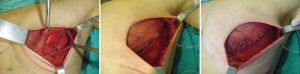

Breast resection is performed using conventional techniques such as axillary dissection or sentinel-node biopsy, which preserve the structure and the sub-groove (groove in the sub-mammary gland) where occurrence of disease is rare (Figures 6 and 7) (20).

The resected tissue should be examined by a pathologist in the operating room, orient, make a mammography, especially in the breast tissue surrounding the tumor and confirm that it is free of disease. Otherwise the surgeon should expand the cutaneous resection. This examination is especially important for in situ carcinomas, and it decreases the risk of LR (Figure 8) (21).

The four primary reconstruction techniques used are: TF, pedicled or a microsurgical flap such as the DIEP flap; temporary or definitive anatomical expanders, with prosthesis indicated exceptionally; extended latissimus dorsi flap; latissimus dorsi flap over prosthesis or expander.

Complications

Necrosis of the mastectomy flaps is an important complication and requires extensive care. Avoiding necrosis is crucial for the final cosmetic result, especially if the reconstruction is performed with an expander and/or prosthesis, where this complication may cause extrusion and failure of the procedure. Necrosis is prevented with meticulous preparation of the mastectomy flaps, which is necessary to optimize the outcomes of the surgical technique. The flaps must be of a uniform thickness to prevent devitalization.

In patients in whom SSM and placement of expanders are indicated, especially in those with an increased risk of necrosis due to special circumstances such as tobacco use (22), it is important to cover the implant with a complete muscular pocket or use acellular dermis to minimize the consequences of a skin complication (Figure 9) (23). If necrosis occurs, whether or not muscular coverage was provided, further surgical exploration is indicated to prevent the loss of the implant.

According to a protocol described in recent publications (24,25) we are making pockets with pectoralis major on the inner upper region of the breast, sutured to a mesh silk (SERI™ Surgical Scafffold, Allergan, California, USA) in the outer lower region achieving full coverage of the expander and evaluate whether this technique provides the same results in terms of complications and aesthetics, which completely muscular pocket (Figure 10).

The patient’s smoking status must also be assessed with regard to the reduction of necrosis. Nicotine is a direct vasoconstrictor that affects the skin; it has an indirect effect on the production of capillary flow by inhibiting release of catecholamines. Non-smoking status is therefore preferred (relative contraindication).

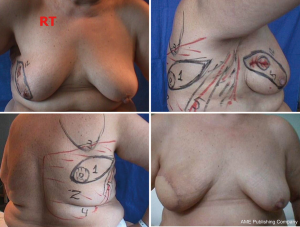

Radiotherapy influences various aspects of surgical planning and outcome. When performed before surgery, it can negatively influence the final aesthetic result and increase the rate of complications (necrosis of skin flaps). When used as an adjuvant treatment or for a LR, it can worsen the aesthetic result according to the type of reconstructive technique employed (26). Therefore, in general, in patients who have undergone previous irradiation and SSM, reconstruction techniques such as DIEP flap and TF are preferred to improve outcomes and favorably influence the preserved skin by preventing necrosis, as these minor procedures help maintain the cosmetic results (Figure 11).

In previous publications, flap necrosis has been reported in 5.6-8% (27) of conventional mastectomies. In SSM, it has been reported in 3-15% of cases depending on the series (28). In our experience, the incidence of flap necrosis was relatively low, at 5.6% (26), possibly related to the care taken in patient selection and optimization of the surgical technique.

Oncological safety

The big question that this technique was in its infancy was his relationship to the risk of higher rates of LR. As is known histological examination of the RL, rarely shows identifiable breast tissue. Traditional literature, in the past associate LR with inadequate surgical technique, determining that recurrences, might result from residual tumor remnants of the intervention.

However, despite the technical variations, LR rates have remained similar over the years (29,30). Therefore, it is clear that there are other predictive factors of LR.

The significance of the LR these findings is not well understood. Current concepts of tumor biology and post-mastectomy LR have pointed to these LRs as “risk markers” of distant metastases (31). Over 90% of LR is detected within 5 years of initial treatment, and 30-60% is associated with simultaneous systemic disease. The prognosis may be more favorable in cases of isolated LR.

Retrospective studies published since the description of the surgical technique by Toth and Lappert in 1991 (6) have analyzed the rate of local relapse.

Kroll et al. (7) reported the first statistical results of the MD Anderson Cancer Center Institute as an LR rate of 1.2%, with a mean of 23.1 months. Following this, several groups published their retrospective experience with mastectomies without skin sparing comparing them with SSM and found no significant differences in the rate of LR, as reported by Cunnick and Mokbel (32).

In our experience, a comparison of the two procedures did not reveal a statistically significant difference in LR rates. With a mean of 68 months, LRs were observed in 5.4% in the SSM group versus 5.1% in the group of not SSM (33).

When we analyze the LR rate of patients who underwent SSM and compare it with the rates reported in randomized prospective studies of mastectomies without reconstruction (31), relapses were found to occur in 2-10% of patients with a follow-up of 6-10 years; these figures are comparable to those of reconstructive procedures that retain skin.

Although, to date, no prospective, randomized study with a control group has been conducted, after more than 20 years of the use of SSM, its LR rates have remained similar, as shown in a meta-analysis conducted by Lanitis et al. (34).

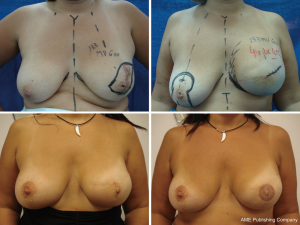

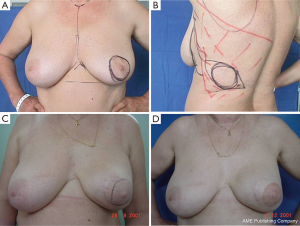

Cosmetic outcome

It is difficult to scientifically address questions on the aesthetic advantages of SSM. We, like other authors (26), are convinced that this technique helps improve reconstruction outcomes by preserving the sub-mammary and skin coverage. This effect has been previously demonstrated by Kroll and colleagues (35,36), who compared immediately BR and delayed BR and highlighted the influence of SSM on outcomes. Correction of symmetry is also influenced by the conservation of skin, as demonstrated in a previous report (37) that compared the TF with expander reconstructions, with and without SSM. It was found that 94% of TF-SSM vs. 50% of TF-NO-SSM cases did not require correction of the opposite breast, and correction was not needed in 12% of the expander-SSM group vs. 4% of the expander-NO-SSM group. We believe that demonstrating the results of the procedure on the basis of the reconstruction and symmetry it achieves is the best evidence for the aesthetic advantages of this procedure (Figures 12-15).

Conclusions

As outlined in the Guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN-2014) (38), SSM is a safe procedure that provides good cosmetic results with good local cancer control. However, the following four prerequisites must be met: experienced surgical team, multidisciplinary evaluation, proper patient selection, and obtaining appropriate margins.

In skin-sparing mastectomy, the choice of location and type of incision, preservation of cutaneous pocket and submammary fold, allows the surgeon to replace the glandular defect with different procedures with the advantage of getting a better aesthetic result, enabling fewer procedures in both the reconstructed breast as in the opposite breast, for symmetry conservation.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bostwick J 3rd, Vasconez LO, Jurkiewicz MJ. Breast reconstruction after a radical mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 1978;61:682-93. [PubMed]

- Radovan C. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy using the temporary expander. Plast Reconstr Surg 1982;69:195-208. [PubMed]

- Johnson CH, van Heerden JA, Donohue JH, et al. Oncologic aspects of immediate breast reconstruction following mastectomy for malignancy. Arch Surg 1989;124:819-23. [PubMed]

- Moran SL, Serletti JM, Fox I. Immediate Free TRAM Reconstruction in Lumpectomy and Radiation Failure Patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;106:1527-31. [PubMed]

- Vinton AL, Traverso LW, Zehring RD. Immediate breast reconstruction following mastectomy is as safe as mastectomy alone. Arch Surg 1990;125:1303-7; discussion 1307-8. [PubMed]

- Toth BA, Lappert P. Modified skin incisions for mastectomy: the need for plastic surgical input in preoperative planning. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991;87:1048-53. [PubMed]

- Kroll SS, Ames F, Singletary SE, et al. The oncologic risks of skin preservation at mastectomy when combined with immediate reconstruction of the breast. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1991;172:17-20. [PubMed]

- Barton FE Jr, English JM, Kingsley WB, et al. Glandular excision in total glandular mastectomy and modified radical mastectomy: a comparison. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991;88:389-92; discussion 393-4. [PubMed]

- Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science 1994;266:66-71. [PubMed]

- Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature 1995;378:789-92. [PubMed]

- Stefanek M, Hartmann L, Nelson W. Risk-reduction mastectomy: clinical issues and research needs. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:1297-306. [PubMed]

- Laronga C, Kemp B, Johnston D, et al. The incidence of occult nipple-areola complex involvement in breast cancer patients receiving a skin-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 1999;6:609-13. [PubMed]

- Petit JY, Veronesi U, Orecchia R, et al. The nipple-sparing mastectomy: early results of a feasibility study of a new application of perioperative radiotherapy (ELIOT) in the treatment of breast cancer when mastectomy is indicated. Tumori 2003;89:288-91. [PubMed]

- Hammond DC, Capraro PA, Ozolins EB, et al. Use of a skin-sparing reduction pattern to create a combination skin-muscle flap pocket in immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;110:206-11. [PubMed]

- Carlson GW, Bostwick J 3rd, Styblo TM, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy. Oncologic and reconstructive considerations. Ann Surg 1997;225:570-5; discussion 575-8. [PubMed]

- Foster RD, Esserman LJ, Anthony JP, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction: a prospective cohort study for the treatment of advanced stages of breast carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2002;9:462-6. [PubMed]

- Chang EI, Ly DP, Wey PD. Comparison of aesthetic breast reconstruction after skin-sparing or conventional mastectomy in patients receiving preoperative radiation therapy. Ann Plast Surg 2007;59:78-81. [PubMed]

- Krohn IT, Cooper DR, Bassett JG. Radical mastectomy: thick vs thin skin flaps. Arch Surg 1982;117:760-3. [PubMed]

- Beer GM, Varga Z, Budi S, et al. Incidence of the superficial fascia and its relevance in skin-sparing mastectomy. Cancer 2002;94:1619-25. [PubMed]

- Behranwala KA, Gui GP. Breast cancer in the inframammary fold: is preserving the inframammary fold during mastectomy justified? Breast 2002;11:340-2. [PubMed]

- Cao D, Tsangaris TN, Kouprina N, et al. The superficial margin of the skin-sparing mastectomy for breast carcinoma: factors predicting involvement and efficacy of additional margin sampling. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:1330-40. [PubMed]

- Pluvy I, Panouillères M, Garrido I, et al. Smoking and plastic surgery, part II. Clinical implications: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Chir Plast Esthet 2015;60:e15-49. [PubMed]

- Becker S, Saint-Cyr M, Wong C, et al. AlloDerm versus DermaMatrix in immediate expander-based breast reconstruction: a preliminary comparison of complication profiles and material compliance. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;123:1-6; discussion 107-8. [PubMed]

- Fine NA, Lehfeldt M, Gross JE, et al. SERI surgical scaffold, prospective clinical trial of a silk-derived biological scaffold in two-stage breast reconstruction: 1-year data. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;135:339-51. [PubMed]

- De Vita R, Buccheri EM, Pozzi M, et al. Direct to implant breast reconstruction by using SERI, preliminary report. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2014;33:78. [PubMed]

- Sbitany H, Wang F, Peled AW, et al. Immediate implant-based breast reconstruction following total skin-sparing mastectomy: defining the risk of preoperative and postoperative radiation therapy for surgical outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;134:396-404. [PubMed]

- Lipshy KA, Neifeld JP, Boyle RM, et al. Complications of mastectomy and their relationship to biopsy technique. Ann Surg Oncol 1996;3:290-4. [PubMed]

- Carlson GW. Risk of recurrence after treatment of early breast cancer with skin-sparing mastectomy: two editorial perspectives. Ann Surg Oncol 1998;5:101-2. [PubMed]

- Agrawal A, Grewal M, Sibbering DM, et al. Surgical and oncological outcome after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Clin Breast Cancer 2013;13:478-81. [PubMed]

- Missana MC, Laurent I, Germain M, et al. Long-term oncological results after 400 skin-sparing mastectomies. J Visc Surg 2013;150:313-20. [PubMed]

- Fisher B, Redmond C, Fisher ER, et al. Ten-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing radical mastectomy and total mastectomy with or without radiation. N Engl J Med 1985;312:674-81. [PubMed]

- Cunnick GH, Mokbel K. Oncological considerations of skin-sparing mastectomy. Int Semin Surg Oncol 2006;3:14. [PubMed]

- González E. ¿Es la conservación de piel en la mastectomía con reconstrucción mamaria inmediata un procedimiento seguro? Consideraciones oncológicas, técnicas y resultados estéticos en una serie de 71 casos Rev Arg Mastol 2002;21:56-80.

- Lanitis S, Tekkis PP, Sgourakis G, et al. Comparison of skin-sparing mastectomy versus non-skin-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Surg 2010;251:632-9. [PubMed]

- Kroll SS. The value of skin-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 1998;5:660-2. [PubMed]

- Kroll SS, Coffey JA Jr, Winn RJ, et al. A comparison of factors affecting aesthetic outcomes of TRAM flap breast reconstructions. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;96:860-4. [PubMed]

- González EG, Cresta Morgado C. Noblía C y col. Reconstrucción mamaria post mastectomía. Rol actual enel tratamiento del cáncer de mama. Prens Méd Argent 2000;87:578-94.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast Cancer. V.2.2014. Available online: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf