Bilateral axillo-breast approach robotic thyroidectomy: review of a single surgeon’s consecutive 317 cases

Introduction

Since the introduction of high-resolution ultrasound in the 2000s, thyroid nodules have increasingly been detected in many countries (1,2), as has the incidence of differentiated thyroid cancer. This may be attributed to the availability of superior diagnostic technology and other indispensable factors. As a result, the demand for thyroid surgery has increased. Traditional surgical treatment of thyroid cancer involves thyroidectomy through a neck incision in 4–6 length. Thyroid carcinoma has a highest incidence rate in young patients aged 20–30 years but also an excellent prognosis. Therefore, patients focus not only on the treatment of cancer but also on the long postoperative neck scar when they assess the surgical results. These scars are exposed easily and can be a serious aesthetic problem (3,4).

In 1996, Gagner et al. reported the first endoscopic subtotal parathyroidectomy. Hüscher et al. performed the first endoscopic thyroidectomy in 1997. The development of a method for endoscopic thyroidectomy has made it possible to eliminate neck scars (5,6). There are two types of endoscopic technology (7); the first is Miccoli’s endoscopic thyroidectomy method. It involves a small incision in the neck and includes approaches made through an endoscopic lateral incision, lateral mini-incision, or post-auricular incision. This method reduces the scar length, making it less obviously visible. The second method is total endoscopic thyroidectomy (TET). It has been developed for scarless neck surgery and has various approaches, including the trans-axillary (TA) approach, the axillo-breast approach, the anterior chest/breast approach, the bilateral breast approach, and the transoral endoscopic approach. The endoscopic procedure has a satisfactory cosmetic outcome; however, performing the operation is difficult, and the learning curve is steeper than that of traditional surgical treatment because of the two-dimensional (2D) camera view and the use of straight, rigid instruments without articulations (8).

Recently, the introduction of the da Vinci Surgical System made it possible to overcome these technical difficulties. The robotic system has a three-dimensional (3D) camera view, hand-tremor filtration, fine motion scaling, and multi-articulated hand-like motions (4,8). In our institution, robotic thyroidectomy (RT) using the bilateral axillo-breast approach (BABA) has been performed since August 2008. The aim of this study was to describe the surgical experience and outcomes of 317 robotic thyroidectomies using BABA.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/gs-21-50).

Methods

Study design and setting

A database of 317 consecutive patients who underwent RT using BABA was reviewed. All cases were performed by a single endoscopic surgeon (HYK) at the Department of Surgery, Korea University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, between July 2008 and July 2016. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Hospital (approval number: ED14085) and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). All patients gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. All patients who underwent RT are included in the study. If the tumor size was larger than 4 cm and there was obvious extrathyroidal extension, we did not recommend RT. Therefore, these patients were excluded from the study. There were 259 cases of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), either through the diagnosis of PTC or suspected PTC upon preoperative fine-needle aspiration (FNA), 20 cases of atypical hyperplasia by FNA, 19 cases of follicular neoplasm, 7 cases of benign neoplasm, and 12 cases of indeterminate nodules. The indications for the operation of benign tumor or indeterminate nodules were as follows: compression symptoms, cosmetic problems, or highly tensile nerves because of the huge tumor. Before the first set of Korean guidelines regarding the management of thyroid nodules was published in 2012, we performed subtotal thyroidectomy for benign thyroid disease and PTC. Since 2012, neck lymph node dissection has been performed in all patients who underwent either thyroid lobectomy or total thyroidectomy for PTC. The operations were performed using a da Vinci robotic system, according to the standard protocols of the Korea University Anam Hospital.

Protocols

The surgical extent was determined based on pathological characteristics, tumor size, and lymph node status, relying on both preoperative imaging and cytology and intraoperative frozen section analysis. We performed subtotal thyroidectomy for benign thyroid tumors in bilateral lobes or PTC of the isthmic portion. Subtotal thyroidectomy was also performed in patients with unilateral benign thyroid tumors. If the thyroid tumor was in unilateral lobe and smaller than 1 cm, lobectomy was considered after written informed consent was obtained. If the tumor size was <4 cm and lymph node enlargement was observed preoperatively or intraoperatively, we performed total thyroidectomy with bilateral central lymph node dissection. If the tumor size was <4 cm without extrathyroidal extension or lymph node enlargement, lobectomy with ipsilateral central lymph node dissection was performed. Total thyroidectomy with ipsilateral central lymph node dissection was performed in cases with extra-thyroidal extension or lymph node enlargement. If the size of the benign nodule was larger than 4 cm, the tissue of the gland was divided into two parts in the endo bag before it was retrieved. A wound drain (100 mL; 3.2 mm in diameter; Barovac, Sewoon Medical, Seoul, Korea) was placed in all cases and removed when the drained volume became less than 20 mL/day. We measured the levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH) during the immediate postoperative period (approximately 3 hours after the thyroidectomy was complete) and the levels of serum calcium and ionized calcium daily. All patients underwent indirect laryngoscopy with a stroboscope before and after the operation. The patients were discharged 2 or 3 days after surgery. The minimum follow-up period was 6 months, to check for persistent complications.

Outcomes

The data for each patient included the following: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), type of thyroid surgery, size of dominant nodule (cm), operative time (min), and duration of hospital stay. Perioperative complications such as hematoma, seroma, infection, vocal cord palsy observed by stroboscopy, and hypoparathyroidism (serum ionized calcium <4.4 mg/dL or PTH <8 pg/mL) were assessed.

Patients were further investigated for adenoma goiter (AG) and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT) 1–2 months after surgery. If the thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level was higher than 9.0, the patient was treated with levothyroxine. All cases of thyroid carcinoma were treated with levothyroxine after surgery. In low-risk cases, TSH level was maintained at 0.2–0.5, whereas in high-risk cases it was maintained at lower than 0.1. Radioactive iodine (I131) treatment was administered in patients with intermediate- to high-risk thyroid carcinoma and total or near total resection was performed. Patients were followed up at the clinic or over the telephone every 3–6 months.

Operative procedures

The BABA was the chosen method of robotic surgery. Most patients used the da Vinci Si system. As the da Vinci Xi system was released in April 2014, a different version was also used. Intraoperative nerve monitoring (IONM) for recurrent laryngeal was performed. In our clinical practice, we used the NIM-Response 3.0 monitoring system (Medtronic Xomed Jacksonville, FL) for IONM. Under general anesthesia with a nerve integrity monitor (NIM) tube, the patient was placed in the supine position with a pillow under the shoulders and the neck slightly extended. Both arms of the patient were kept in an adducted position with slight posterior extension to expose the axilla. After cleaning and draping, the skin flap was marked at the anatomic landmarks of the thyroid notch, cricoid cartilage, sternal notch, midline of the neck, the superior border of the clavicle and the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscles (SCM). A line was drawn 2 cm below the superior border of the clavicle. After marking the four incisions in the bilateral circumareolar and bilateral axillary areas, four trajectory lines were drawn, extending from the incision sites toward the cricoid cartilage. The space enclosed by the marked lines was the flap area. Hydrodissection of the skin flap was performed by injecting diluted epinephrine (1:200,000) into the flap area. Bilateral 12 mm circumareolar incisions and bilateral 8 mm axillary incisions were made. Blunt dissection under the four trajectory lines was performed first using the tunneler, then followed by blunt dissection under the flap area. Trocars of 8–12 mm were inserted after the flaps were raised. The superficial approach was performed for the working space, and there were no unpredicted complications, such as injuries to the brachial plexus or the axillary vein. The work space was maintained using CO2 insufflation at 6–9 mmHg, and the robotic system was docked. The camera was inserted through the right breast port with a Harmonic ACE scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) through the left breast port. Additional Maryland dissecting forceps (Aesculpa, Inc., Center Velley, PA, USA) and ProGrasp forceps (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) were inserted into the bilateral axillary ports. The midline was dissected using a monopolar electrocautery hook and a harmonic scalpel. The isthmus was divided by a harmonic scalpel to facilitate lateral and posterior dissection of the gland. We dissected the space between the upper pole of the thyroid gland and the cricothyroid muscle, thereby allowing optimal visualization of the superior thyroid artery. Then, the superior thyroid blood vessel was ligated and divided using the harmonic scalpel. Subsequently, cephalad dissection around the thyroid was initiated, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) near the inferior thyroidal artery or the tracheoesophageal groove was dissected and identified using IONM. The parathyroid gland was identified when the posterior gland was dissected. The lobe was delivered using a Lap Bag, checked carefully for the presence of parathyroid, and then sent for obtaining a frozen section. The cervical node dissection (CND) was performed if a malignant nodule was identified, and the contralateral lobe was removed, if necessary. When lateral neck lymph node dissection was needed, the skin flap was created up to the posterior border of the SCM muscle. The space between the strap and SCM muscles was divided into carotid arteries. Then, the node was removed from levels IIA, III, and IV After achieving hemostasis and washing, a suction drain was inserted through the axillary port. The midline was closed using continuous vicryl sutures. The skin incision was closed by suturing with a buried knot with vicryl, and then skin tape was attached. We performed compression dressing with a surgical pad on the breast and superior anterior chest wall.

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables, and independent two-sample t-tests were used to compare the values of continuous variables. The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or number (%) as appropriate. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS software (version 21.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

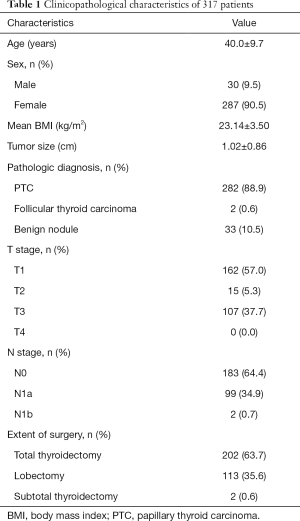

As can be seen from Table 1, there were more female patients than male patients in the RT group (287 cases, 90.5%). The mean age was 40.0±9.7 (range, 16–63) years. There were 103 (32.5%) patients aged ≥45 years. The maximum diameter of a benign nodule was 5.8 cm, and the maximum diameter of a malignant tumor was 3.5 cm. Total thyroidectomy was performed in 202 (63.7%) patients and lobectomy in 113 (35.6%) patients. Total thyroidectomy with CND was mainly performed in 194 cases (61.2%), followed by lobectomy with CND in 81 cases (25.6%), and lobectomy in 29 cases (9.1%). In three cases, simultaneous lateral neck lymph node dissection was performed. One patient underwent reoperation because of recurrent PTC in the other lobe. There was a case of total thyroidectomy after radiofrequency ablation. According to the pathologic results, PTC was the most common indication for thyroidectomy (n=282, 88.8%), followed by benign nodules (n=33, 10.5%) and follicular thyroid carcinoma (n=2, 0.6%). Papillary thyroid microcarcinomas (PTMCs) were present in 230 (72.5%) patients. Seven cases (2.2%) had a follicular variant of papillary carcinoma, 2 cases had minimally invasive follicular thyroid carcinoma, and 2 had HT. AG was present in 31 cases. There were 107 cases of T3 tumors because of minimal extrathyroidal extension, but no patient had T4 tumors.

Full table

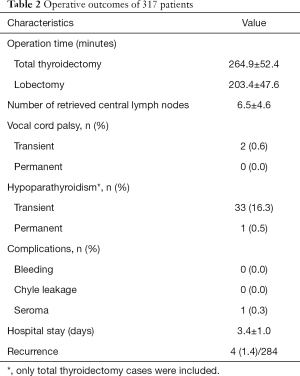

Table 2 shows the mean operation time for total thyroidectomy and lobectomy, which was 264.9±52.4 and 203.4±47.6 min, respectively. In the total thyroidectomy group, the operative time in male patients (295±51 min) was longer than that in female patients (263±52 min) (P=0.01). However, sex had no effect on operative time in the lobectomy group. To evaluate the relationship between BMI and the difficulty of surgery, we analyzed the operative time for total thyroidectomy and lobectomy as well as postoperative complications. As Table 3 shows, BMI had no effect on the operative time, rate of vocal cord palsy, and postoperative hypoparathyroidism.

Full table

Full table

Regarding postoperative complications, 2 patients had transient vocal cord palsy (0.6%, 2/317). There were no cases of permanent vocal card palsy. Thirty-four (16.8%) patients had hypoparathyroidism, 33 (16.3%) of which were transient. One patient was diagnosed with permanent hypothyroidism 6 months after the operation (0.5%). One patient had a postoperative seroma. All patients were followed up at the clinic or over the telephone.

Four patients (1.4%) had local recurrence after a median follow-up of 61±23 months. Local recurrences occurred in four patients within 2 years after surgery. The patients’ demographics were one male and three females with mean age 35.7 (range, 22–44) and mean BMI 22.572. The recurrence sites were paratracheal lymph node in two cases, single lymph node on level III in one case and contralateral thyroid PTC with lateral lymph node metastasis in one another case. For treatment, radioablation were performed after open CND in two patients with paratracheal lymph node metastasis, robotic modified radical neck dissection (MRND) was performed in one patient with single lymph node metastasis, and robotic completion lobectomy + MRND was performed in the last case.

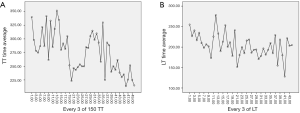

The learning curve for the BABA RT was evaluated from July 2008 to July 2016. In the total thyroidectomy group, 150 cases were analyzed because of the restriction of the IBM SPSS software. As shown in Figure 1, a decrease in operation time in total thyroidectomy was observed after 49–51 cases (P=0.015), which is considered the learning curve (Figure 1A). The 51st patient who underwent thyroidectomy was the 70th to undergo the BABA RT procedures. At the middle of the graph, the operation time increased again after cases 79–81 because several cases of hypoparathyroidism had occurred. After cases 100–102, the operation time markedly decreased again. In addition, there were only 8 cases of lobectomy before the 30th case at the early stage of BABA RT, and there were 14 cases before the 70th patient. As the number of lobectomies increased, the operation time slightly decreased (P=0.02) (Figure 1B).

Discussion

The application of robotic systems offers many potential advantages over traditional open thyroidectomy and endoscopic thyroidectomy, including improved surgical ergonomics and surgical dexterity. The most important merits were the excellent surgical view in 3D, 10- to 15-fold magnification, and multi-articulated hand-like motions. The 30° endoscopy camera helps make the robotic surgery field look similar to that in open surgery. The high-resolution enlarging 3D vision makes the local anatomy clearer. The robotic instruments can be driven in multi-angular motion by the second joint in the instrument tip, which is more like the motions of the human wrist, unlike endoscopic instruments that cannot do this (8-10). In addition, the advantages of RT include the ability of patients to rapidly return to work as well as reduced discomfort in the neck. Since the introduction of RT, many studies have reported on its technical safety, feasibility, and favorable outcomes in the treatment of PTC (11). We compared robotic surgery results with open conventional thyroidectomy results. The mean numbers of metastatic lymph nodes in the central compartment neck dissection and postoperative complications were comparable with those of open thyroidectomy. This result is supported by the studies of Kim et al. and Seup et al. (4,12). Postoperative serum TG levels were equivalent between robotic and open conventional thyroidectomy, and lower in RT than in endoscopic thyroidectomy (13).

There are various surgical approaches for RT, such as BABA, double incision gasless TA approach, retro-auricular (RA) approach, TA approach, infraclavicular approach, and so on. We chose BABA (4,11-14) for the following reasons: first, it allows for good cosmetic outcomes. BABA allows remote access to the thyroid space without the need for a cervical incision. The small circumareolar and axillary scars were nearly invisible (15,16). Second, BABA provides a symmetric surgical view of important anatomical structures, such as the thyroid vessels, parathyroid glands, RLNs, and carotid artery, making it easier to perform bilateral total thyroidectomy and radical neck dissection (12,17). Finally, we have much more experience with endoscopic thyroidectomy using BABA.

The indications and contraindications for RT were not consistent. Most surgeons think the ideal patients are thin female patients with a small unilateral nodule (<3 cm), without history of HT, and a desire to avoid a neck incision (18). Total thyroidectomy required more time in men than in women, but the operative time for lobectomy did not differ significantly between the sexes. Lobectomy requires a short duration, but docking of the robotic system alters the duration of the procedure thus affecting the analysis of the results. Sex is a factor that affects surgical difficulty; thus, female patients are the preferred subjects for RT. Patients who underwent total thyroidectomy, lobectomy, and lobectomy plus CND were divided into two groups, BMI <25 and BMI ≥25. We found that BMI had no influence on operative time and postoperative complications. Fat should not be a factor that influences the decision for robotic surgery. Regarding the size of the nodule, Jeong et al. suggested that follicular neoplasms or benign thyroid nodules should be less than 5 cm in diameter and differentiated thyroid carcinoma should be less than 3 cm at its largest diameter (19). In our study, the largest diameter of a benign nodule was 5.8 cm and a malignant nodule was 3.5 cm. We believe that benign nodules can be considered up to 6 cm and malignant nodules up to 4 cm. In another study, it was confirmed that thyroiditis was not a factor that caused difficulty in RT (17). However, we found that operative exudation was more common in patients with thyroiditis, which disturbed the operative procedure. Nevertheless, thyroiditis is not a contraindication for RT.

We have provided the following indications and contraindications based on our experience: anyone with benign nodules (≤6 cm), such as adenoma, goiter, and indeterminate neoplasia or follicular neoplasm, can choose RT if they want to avoid the neck incision. If DTC is diagnosed, T1 and T2 tumors can be removed through the robotic system. In addition, many cases of T3 tumors without obvious extrathyroidal extension were treated at our hospital. However, the patients were excluded that have high BMI, thyroiditis symptom, or large tumors >4 cm at the initial stage. The initial procedures may be difficult because of the risk of hypoparathyroidism. The absolute contraindication at our institution was poorly differentiated or undifferentiated cancer. Relative contraindications are thyroid carcinoma that is large in size or with severe cervical lymph node metastasis that may indicate extrathyroidal extension, including invasion of the RLN and esophagus/trachea. Lateral cervical lymph node metastasis is not an absolute contraindication. In the present study, lateral cervical lymph node dissection was performed in three patients, which was very small. However, according to the study by Seup et al., there was no difference in the number of retrieved lymph nodes, metastatic lymph nodes, and stimulated thyroglobulin levels between robotic MRND by BABA and conservative open thyroidectomy (12). MRND does not routinely include level I, IIB, and VA lymph nodes. Robotic MRND using BABA is safe and shows oncologic and postoperative outcomes comparable to those of the open procedure. If there is no severe cervical lymph node metastasis, robotic lateral neck node dissection can be performed using BABA. In addition, there was one patient who underwent reoperation and one patient who underwent RFA. The case of reoperation had undergone lobectomy in the first surgery and we performed lobectomy of the other side. If there are no obvious adhesions, reoperation or post-RFA are not contraindications for RT.

In both open thyroidectomy and RT, the prevention of complications is essential. In our study, the rate of transient vocal cord palsy was 0.6% (2/317), and there was no permanent vocal cord palsy. The procedure we followed to avoid RLN injury was as follows. And continue the text in the past tense. We are familiar with the anatomy of the RLN and skilled at dissection using IONM. The first part is located under the lower pole of the thyroid gland through the para-tracheal tissue. The second is from the inferior border of the Zuckerkandl Tubercle (ZT) or about 1 cm inferior to the RLN entry point of the larynx to the lower pole of the thyroid gland, where the relation between the RLN, the Berry ligament, and the ZT is very close and complex. The third part is from the inferior ZT to the entry point of the larynx. Cervical RNLs may divide into several branches prior to diving into the larynx. According to Randolph, 50–60% of patients have some small branches of the RLN to the trachea, esophagus, or inferior constrictor muscle, but only 30% have true RLN extra-laryngeal branches (anterior and posterior branches) that enter the larynx (20,21). When extra-laryngeal branches are present, they usually exist at the level of the ligament of Berry. We identified the RLN in the second part. When dissecting the lower pole of the thyroid gland, we made sure to be close to the capsule. After the lower pole was free, we looked for the RLN using IONM. We could find the RLN only by using Maryland dissecting forceps under the IONM. Using the IONM, we located the RLN with a stimulation level of 2.0 mA. Then, according to the location, the RLN was dissected and identified with a stimulation level of 1.0 mA. Because of the very tight tissue structure and the existence of extra-laryngeal branches, more attention should be paid to the dissection of the third part of the RLN. In addition, since the right hand is dominant in most people, there are some differences between the right and left sides. On the left side, we dissected the outside of the RLN first, but on the right side we dissected the ligament of Berry first. When finding the branch of the RLN, we identified if there was a motor branch by IONM with a stimulation level of 1.0 mA. Sometimes, even when the motor branch was very difficult to distinguish from the sensory branch or a small artery, the IONM was used with a stimulation level of 0.6 or 0.8 mA in order to avoid the interference of stimulation electric current. During the dissection of the RLN, caution was taken, and the surgical field was kept clean.

The rate of transient hypoparathyroidism was 17% in patients who underwent total thyroidectomy with CND, and the rate of permanent hypoparathyroidism was 0.5%. Because the robotic system can magnify the surgical field by 10- to 15-fold, the parathyroid gland was relatively easy to identify. However, the harmonic scalpel can cause thermal injury to the parathyroid gland. Sufficient distance should be maintained from the parathyroids, approximately 3–5 mm. In addition, the specimens should be carefully examined. If the parathyroid gland is removed, immediate parathyroid auto-transplantation (IPA) should be performed.

Conclusions

With the advancement in technology, RT using BABA is feasible and safe except in cases with poorly differentiated or undifferentiated carcinoma, benign tumors larger than 6 cm, and T3 or T4 stage carcinoma. In RT, the prevention of injury to the RLN and parathyroid is the most important cautionary step. Of course, there are also some disadvantages, such as high cost and long operative time. However, the merit of the better cosmetic result and excellent telescopic visualization and the robotic arm’s wrist-like capability are superior. With the reduction in the cost of robotic material consumption, more patients will choose RT.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ji Young Won and Woong Hyun Lee for the illustration.

Funding: This work was supported by a Korea University grant (K2014031).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/gs-21-50

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/gs-21-50

Peer Review File: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/gs-21-50

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/gs-21-50). GD serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Gland Surgery from Dec 2016 to Nov 2022. RPT serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Gland Surgery from May 2015 to Aug 2022. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Hospital (approval number: ED14085) and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). All patients gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ministry of Health & Welfare. Korea Central Cancer Registry. 2015. Available online: https://ncc.re.kr/main.ncc?uri=manage02_1

- How J, Tabah R. Explaining the increasing incidence of differentiated thyroid cancer. CMAJ 2007;177:1383-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schneider DF, Chen H. New developments in the diagnosis and treatment of thyroid cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2013;63:374-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim WW, Jung JH, Park HY. A single surgeon's experience and surgical outcomes of 300 robotic thyroid surgeries using a bilateral axillo-breast approach. J Surg Oncol 2015;111:135-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gagner M. Endoscopic subtotal parathyroidectomy in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Br J Surg 1996;83:875. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hüscher CS, Chiodini S, Napolitano C, et al. Endoscopic right thyroid lobectomy. Surg Endosc 1997;11:877. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong KP, Lang BHH. Endoscopic thyroidectomy: a literature review and update. Curr Surg Rep 2013;1:7-15. [Crossref]

- Kwak HY, Kim HY, Lee HY, et al. Robotic thyroidectomy using bilateral axillo-breast approach: Comparison of surgical results with open conventional thyroidectomy. J Surg Oncol 2015;111:141-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tae K, Ji YB, Jeong JH, et al. Comparative study of robotic versus endoscopic thyroidectomy by a gasless unilateral axillo-breast or axillary approach. Head Neck 2013;35:477-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tae K, Ji YB, Jeong JH, et al. Comparative study of robotic versus endoscopic thyroidectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012;147:55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee YM, Yi O, Sung TY, et al. Surgical outcomes of robotic thyroid surgery using a double incision gasless transaxillary approach: analysis of 400 cases treated by the same surgeon. Head Neck 2014;36:1413-9. [PubMed]

- Seup Kim B, Kang KH, et al. Robotic modified radical neck dissection by bilateral axillary breast approach for papillary thyroid carcinoma with lateral neck metastasis. Head Neck 2015;37:37-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jackson NR, Yao L, Tufano RP, et al. Safety of robotic thyroidectomy approaches: meta-analysis and systematic review. Head Neck 2014;36:137-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Byeon HK. Comprehensive application of robotic retroauricular thyroidectomy: The evolution of robotic thyroidectomy. Laryngoscope 2016;126:1952-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choe JH, Kim SW, Chung KW, et al. Endoscopic thyroidectomy using a new bilateral axillo-breast approach. World J Surg 2007;31:601-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu SYW, Wong SKH, Chiu PWY, et al. Endoscopic thyroid lobectomy using bilateral axillo-breast approach: surgical techniques and outcomes. Surg Pract 2015;19:128-32. [Crossref]

- Kwak HY, Kim HY, Lee HY, et al. Predictive factors for difficult robotic thyroidectomy using the bilateral axillo-breast approach. Head Neck 2016;38:E954-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuppersmith RB, Holsinger FC. Robotic thyroid surgery: an initial experience with North American patients. Laryngoscope 2011;121:521-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeong JJ, Kang SW, Yun JS, et al. Comparative study of endoscopic thyroidectomy versus conventional open thyroidectomy in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC) patients. J Surg Oncol 2009;100:477-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiang FY, Lu IC, Chen HC, et al. Anatomical variations of recurrent laryngeal nerve during thyroid surgery: how to identify and handle the variations with intraoperative neuromonitoring. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2010;26:575-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Randolph GW. Surgical anatomy of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. In: Randolph GW. editor. Surgery of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2003:300-42.