Oncoplastic techniques in breast surgery for special therapeutic problems

Special therapeutic problems in benign breast conditions

Benign proliferative breast lesions are most frequently observed in women 30 to 40 years of age, sometime causing significant breast asymmetry because of the large size. The differential diagnoses for these lesions include pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), benign phyllodes tumors, juvenile fibroadenoma, and giant fibroadenoma with increased stromal cellularity. The principles of surgical treatment are different for each diagnostic category. The crucial steps in management consist of preoperative tissue diagnosis and surgical techniques for breast reconstruction after removal of the tumor.

Core needle biopsy (CNB) is preferable to fine needle aspiration for preoperative tissue diagnosis, because fibroadenomas and phyllodes tumors have similar cytologic features. Clinical findings that could increase the suspicion of phyllodes tumors include older patient age, larger tumor size, and history of rapid growth (1). The major pathological feature that distinguishes a phyllodes tumor from a giant fibroadenoma is the cellularity of the stromal component in the former (2). However, the histologic features of benign phyllodes tumors can be difficult to distinguish from those of fibroadenomas on CNB.

It is common for a CNB of either a phyllodes tumor or fibroadenoma to be interpreted as a “fibroepithelial lesion”, hence a phyllodes tumor cannot be ruled out in such a situation. The clinical challenge for the surgeon is to decide whether to remove the entire lesion for management, as is done for a typical fibroadenoma, or to excise the lesion with wide margins, as is therapeutically indicated for phyllodes tumors. If large benign phyllodes tumors are excised with narrow or no margin, reexcision should be performed. Several publications advocated margins of at least 1 cm as adequate (3,4).

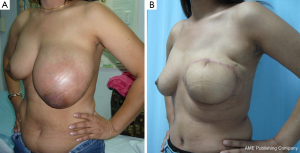

Appropriate techniques for breast reconstruction are crucial after removal of a large benign tumor. Lesions with microscopic appearance of a conventional fibroadenoma, however large, should still be classified as fibroadenomas and may be managed adequately by enucleation. Cosmetic sequelae after enucleation of large tumors are common. If an estimated 20% to 50% of breast volume has been resection, a type II breast deformity can occur (5). Reshaping the breast by using a “round block” technique such as the periareolar Benelli mastopexy is required to correct the defect after removing a large volume of the tumor (Figure 1A-C) (6). If total mastectomy is considered for a large benign phyllodes tumor, then a free flap or a pedicled flap such as a pedicled transverse rectus abdominis (TRAM) flap can be used to reconstruct the breast (Figure 2A,B).

Special therapeutic problems in malignant conditions

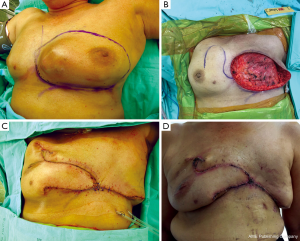

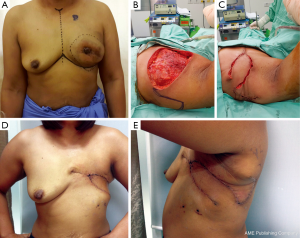

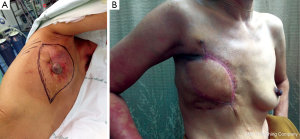

In patients with a CNB result interpreted as “malignant phyllodes tumor”, the crucial information is whether the tumor to breast size ratio is favourable (e.g., a low ratio) or not. A pseudocapsule of dense, compressed, normal tissue, often containing microscopic malignant cells, surrounds malignant phyllodes tumors. As a result, more tissue typically needs to be removed to achieve adequate margins (7). Simple mastectomy without axillary dissection has been recommended for malignant phyllodes tumors with high tumor to breast size ratio. Margins can be typically wider than 1 cm, but a width greater than 2 cm is associated with the lowest risk of recurrence (8). After removing the tumor with negative margins, a large skin and soft tissue defect can be covered with a pedicled TRAM flap reconstruction (Figure 3A-D). In a patient who presented with local recurrence (LR) after performing left breast conservative treatment (BCT) for a malignant phyllodes tumor, and who also had large breasts with severe ptosis, we performed a restaging work-up to rule out distant metastases. The majority of such patients with LR after BCT are treated with mastectomy, although the use of repeat breast conservation surgery for LR has been reported (9). In the case of our patient, after a restaging work up ruled out distant metastasis, we performed a left mastectomy, and a reduction mammoplasty of the opposite breast to reduce breast weight, with a good cosmetic result (Figure 4A,B) (10). A reduction mammoplasty in the present setting can help relieve back pain and achieve good body balance, with only one remaining but smaller breast.

Special therapeutic problems in the palliative setting

Breast cancer patients who have concurrent distant metastases (stage IV disease) are primarily treated by palliative systemic therapy. Surgical removal of the breast tumor does not provide survival benefit. On occasion the primary tumor is removed in these patients for palliative reasons, such as for disabling pain, infection, ulceration or bleeding. Nonetheless, these patients should be initiated on systemic therapy as the first-line treatment. Patients who respond to systemic therapy, or have persistent but non-progressive metastatic diseases, with good performance status, may be considered for palliative or salvage surgery for quality of life (QoL) reasons. The QoL benefits have been highlighted in a recent study (11). A salvage resection is defined as the resection of all visible lesions, extending to the surrounding skin with a safety margin of at least 2 cm (12). Closure or reconstruction of the soft tissue defect of the chest wall can be performed using skin grafts or different types of vascularized pedicled musculo-cutaneous flaps.

The choice of closure or reconstruction methods depend on the location and size of the defect, availability of the local and pedicled flaps, previous surgery or radiotherapy at the donor and recipient site, and the general condition of the patient. Direct simple closure is possible for small lesions. Skin grafts can be used for superficial chest wall defects involving only the soft tissue. Previous or post-operative radiation therapy may compromise the healing of skin grafts.

Local flaps

Breast flap

The breast parenchyma can be used as a flap to cover defects located predominantly in the midline (Figure 5A-D). This flap is suitable for elderly patients with associated comorbidities, because of the short operative time required. The blood supply of breast flap is good, but the cosmetic outcome is rather poor (13).

Random skin flap from the lateral chest wall

This flap can cover small and moderate sized defect on the anterior and lateral aspects of the chest wall, and can be used in combination with the other flaps (Figure 6A-E). It is also suitable for the elderly, or for patients with poor functional status, due to the short operative time. The weakness of this method is a lack of sufficient volume to cover large defect.

Pedicled flaps

The regional pedicled musculocutaneous flaps available for reconstruction include the latissimus dorsi (LD) flap or TRAM flap. We prefer the use of the LD flap when available, and it is usually large enough to cover most defects (Figure 7A,B). The LD flap can be rotated widely, is easy to harvest, and can be tailored to cover the anterior, lateral, and posterior regions of the chest wall. In addition, this technique can be performed within a relatively short period of time, and patients experience fewer postoperative complications afterwards.

Complications of oncoplastic surgery after radiation

Previous studies suggested that the surgeon should be more cautious in performing oncoplastic surgery in patients with irradiated breasts. The study by Losken et al. suggested that radiation therapy might decrease compliance of the covering soft tissue (14). Our results demonstrate that oncoplastic surgery is a simple and reliable technique to correct nipple areola complex (NAC) malposition after previous breast procedures, even in those patients who previously underwent locoregional radiotherapy that could negatively affect wound healing and graft intake (15).

In previously irradiated patient, our experience showed a mastectomy skin flap necrosis occurred after performing nipple sparing mastectomy (NSM) with LD flap plus implant reconstruction (Figure 8A-D). This finding may due to the individual surgeon’s technique. The surgeon must carefully make the dissection of the gland more precisely and the preservation of the subdermal vessel network to the cutaneous flaps. To reduce severity of necrotic complications, the reconstruction should be performed with autologous flap (LD flap, TRAM flap) with the use of an additional implant. When mastectomy skin flap or NAC necrosis occurred, we sometimes performed only skin flap debridement with or without NAC and we did not remove implant because the flap could protect and cover it.

Conclusions

Breast reconstruction techniques are of crucial importance after removal of large benign proliferative lesions with an adequate margin. For large phyllodes tumors, oncoplastic surgery can prevent and correct breast deformities after adequate removal with wide margins, resulting in a good cosmetic outcome. Larger soft tissue and skin defects can be closed using oncoplastic methods. Salvage mastectomy and reconstruction for stage IV breast cancer is a feasible procedure, providing adequate local disease control and excellent palliation of very disabling symptoms in selected patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge their clinical fellows team as follows: Dr. Natthapong Saengow, Dr. Rujira Panawattanakul, Dr. Saowanee Kitudomrat, Dr. Paweena Luadthai, Dr. Pongsakorn Srichan and Dr. Piyawan Kensakoo to encourage these operations.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Gabriele R, Borghese M, Corigliano N, et al. Phyllodes tumor of the breast. Personal contribution of 21 cases. G Chir 2000;21:453-6. [PubMed]

- Ashikari R, Farrow JH, O'Hara J. Fibroadenomas in the breast of juveniles. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1971;132:259-62. [PubMed]

- de Roos WK, Kaye P, Dent DM. Factors leading to local recurrence or death after surgical resection of phyllodes tumours of the breast. Br J Surg 1999;86:396-9. [PubMed]

- Reinfuss M, Mituś J, Duda K, et al. The treatment and prognosis of patients with phyllodes tumor of the breast: an analysis of 170 cases. Cancer 1996;77:910-6. [PubMed]

- Clough KB, Cuminet J, Fitoussi A, et al. Cosmetic sequelae after conservative treatment for breast cancer: classification and results of surgical correction. Ann Plast Surg 1998;41:471-81. [PubMed]

- Benelli L. A new periareolar mammaplasty: the "round block" technique. Aesthetic Plast Surg 1990;14:93-100. [PubMed]

- August DA, Kearney T. Cystosarcoma phyllodes: mastectomy, lumpectomy, or lumpectomy plus irradiation. Surg Oncol 2000;9:49-52. [PubMed]

- Belkacémi Y, Bousquet G, Marsiglia H, et al. Phyllodes tumor of the breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;70:492-500. [PubMed]

- Galper S, Blood E, Gelman R, et al. Prognosis after local recurrence after conservative surgery and radiation for early-stage breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;61:348-57. [PubMed]

- Dennis CH. Reduction Mammaplasty and Mastopexy: General Considerations. In: Spear SL, editor. Surgery of the breast: principles and art. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005:972-5.

- Levy Faber D, Fadel E, Kolb F, et al. Outcome of full-thickness chest wall resection for isolated breast cancer recurrence. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;44:637-42. [PubMed]

- Veronesi G, Scanagatta P, Goldhirsch A, et al. Results of chest wall resection for recurrent or locally advanced breast malignancies. Breast 2007;16:297-302. [PubMed]

- Tukiainen E. Chest wall reconstruction after oncological resections. Scand J Surg 2013;102:9-13. [PubMed]

- Losken A, Pinell XA, Sikoro K, et al. Autologous fat grafting in secondary breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 2011;66:518-22. [PubMed]

- Rietjens M, De Lorenzi F, Andrea M, et al. Free nipple graft technique to correct nipple and areola malposition after breast procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2013;1:e69. [PubMed]