Nipple areola complex sparing mastectomy

Introduction

Breast conservative therapy (BCT) is the gold standard in the treatment of the majority of women with early breast cancer (BC) (1). BCT provides long-term survival rates equivalent to those of total mastectomy while preserving the breast (2).

However, approximately one-third of women still require a mastectomy, because of their own preference or because a breast-conserving therapy would not be compatible with the distribution of the disease and the tumor size (with respect to the breast size), either from the oncological or aesthetic point of view.

Nowadays oncological breast surgery has to be performed sparing no effort in maximizing also cosmetic results, and even mastectomies, when unavoidable, should conform to acceptable aesthetic results (3).

Respecting these concepts, today we have on tap the so-called “conservative mastectomies” which entail the removal of all the breast parenchyma together with the tumour, while saving the skin envelope of the mammary gland and therefore leaving the patient with a normal breast appearance after the reconstruction procedure (4).

The most conservative procedure is nipple-areola-complex sparing mastectomy (NSM), which involves the complete glandular dissection and preserves the whole skin mantle, including the nipple-areola-complex (NAC). It is of course an invasive procedure, but safeguarding the integrity of the NAC, which removal is recognized as a factor that exacerbates the patient’s feeling of mutilation (5), offers acceptable cosmetic results.

There have been some controversies regarding the oncologic safety of this procedure, and the NSM has also introduced a set of complications that were not a concern with total mastectomy, such as nipple and areolar necrosis (6).

Indications

The overarching principle guiding surgical management of women with BC remains oncological safety.

Careful selection of candidates to NSM is imperative and requires a combination of good clinical assessment with modern imaging techniques.

NSM may be indicated in order to treat extensive or multicentric DCIS and LCIS, multifocal/multicentric invasive ductal or lobular carcinomas (more than 2 cm distant from nipple, without skin involvement and/or pathologic discharge from the nipple) and BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Beyond the oncological indications, the conventional NSM procedure is suitable for small-medium breasts only (NAC-inframammary fold distance <8 cm), when breast conserving surgery is likely to result in unsatisfactory cosmetic results or when in keeping with patient’s preference (7).

Conversely, carcinoma infiltrating the skin and/or NAC (cancer within 2 cm from the base of the nipple), inflammatory carcinoma, pathologic discharge from the nipple (C4-C5) and nipple Paget’s disease are considered absolute contraindications to NSM.

Previous radiotherapy, active smoking, diabetes, obesity, recent peri/subareolar surgery, large and ptotic breasts (NAC-inframammary fold distance >8 cm, NAC below the infra-mammary crease and suprasternal notch to nipple distance of 26 cm or more) and extensive lympho-vascular invasion are considered relative contraindications. Patients with large breasts or with grade 3-ptosis are not encouraged to have this procedure because of the increased risk of nipple necrosis and asymmetries.

Surgical technique

The current nipple-sparing mastectomy technique is a feasible procedure with a low rate of postoperative complications.

The goal of the breast surgeon is to remove the breast glandular tissue while maintaining a viable skin envelope.

All patients undergo a preoperative clinical and instrumental evaluation consisting in anamnesis, physical examination, mammography, ultrasonography and, when available, magnetic resonance images (MRI) which appears essential to determine nipple and retroareolar morphology.

Skin incisions

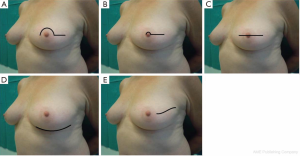

The choice of incision appears to affect cosmesis, technical ease in performing the operation and vascular viability of the nipple.

Sacchini et al. (8) described four different types of skin incisions for NSM. The periareolar incision with lateral extension can be performed on the inferior or superior areolar edge. This allows excellent exposure for the dissection of the retroareolar ducts and lateral breast tissue and bleeding can be easily controlled. The lateral extension can extend up to 7 cm, facilitating dissection of the lateral margin of the pectoral muscle for implant placement. This incision, however, may compromise blood supply at the periphery of the skin flaps and areola, and can cause ischemia of the areola. This kind of incision is no longer practically used. The transareolar incision with peri-nipple and lateral-medial extension may reduce the risk of ischemia to the lower portion of the areola. The possible sequelae of this incision is downward nipple projection caused by the peri-nipple scar formation. The trans-areolar and trans-nipple incision with medial and lateral extension involves bivalving the nipple. This incision does not compromise the vascularity of the nipple or areola and provides the best exposure to the retro-areolar ducts. The mammary crease incision can be performed inferiorly or laterally for a length of 8-10 cm (9). With this incision, the scar is the least evident, and the vascularization of the skin flap is preserved by the superior and medial vessels. However, access to the breast parenchyma in the parasternal and subclavicular regions is limited, and adequate removal of tissue in these regions may be compromised. The italic S incision extends from 1 cm out of the lateral edge of the areola to the external equatorial line and allows for easy access to all breast quadrants and also permits an access to axillary lymph nodes (Figure 1).

Rawlani et al. (10) investigated the effect of incision choice on nipple necrosis and outcomes of NSM; periareolar incision resulted in significantly more cases of nipple necrosis compared with the lateral or infra-mammary incisions (31.8% vs. 6.25%) and in 23.8% of cases nipple necrosis was complete.

Glandular dissection

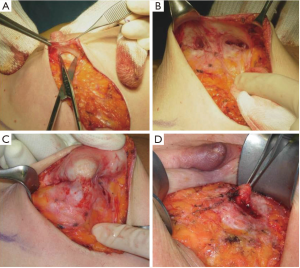

Following incision, skin flaps are raised in most instances using electrocautery. It is recommended to find the plane between the subcutaneous fat and the breast glandular tissue, to detach the superior part of the breast by dissecting the Cooper ligaments first and then remove the mammary gland along the pectoralis major fascia (9). The dissection should preserve, whenever it is possible, the subcutaneous fat layer and its blood vessels (11). Under the NAC, the breast glandular tissue closely adheres to the overlying dermis with little or no fat interposed.

The NAC is elevated just beneath the level of the deep dermis. Following breast removal, by nipple eversion the central ducts are transected at the base of the nipple. Dissection of the ducts should be performed with scissors rather than with electrocautery to avoid thermal damage to the subdermal vascular network of the NAC.

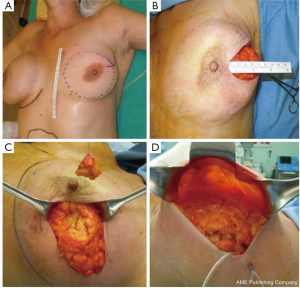

In our surgical practice NAC isolation is performed by hydrodissection of the areola: a 20 cc saline solution containing 2.5 mcg/mL of adrenaline is injected into the deep sub-areolar dermis to obtain complete detachment of the skin (Figure 2), then the areola is isolated by dissecting the swollen plane with scissors and the nipple may be cored without increasing the risk of ischemic complications (12) (Figure 3).

Hydrodissection causes swelling and widening of the virtual spaces among connective tissue fibers in the subdermal plane. As nipples survive on the blood supply from dermal vessels (13), NAC isolation along a plane that extends deep into the dermis is thought to cause minimal vascular injury to the nipple, thus maintaining its viability; adrenaline is commonly used in surgical practice to keep bleeding to a minimum, a procedure that eliminated the need to use the cautery which, in itself, could damage the dermal vessels of the nipple.

Retroareolar tissue specimen is sent for intra-operative frozen section biopsies or evaluated with permanent histology. If the tissue results positive for carcinoma the NAC is removed.

Breast reconstruction

The preservation of the whole skin envelope and the NAC implies the necessity of immediate breast reconstruction, either with a tissue expander/permanent implant in a submuscolar pocket, or with autologous flaps (DIEP, GAP, TRAM).

If a prosthetic reconstruction is chosen, a directo-to-implant procedure is normally performed for small sized breasts because it is likely that minimal expansion of the subpectoral pocket is required. A two-stage reconstruction is otherwise performed in medium-sized breasts because the pocket tissue has to be expanded by a temporary expander before inserting a large prosthesis (14).

Schneider et al. demonstrated that NSM and free-flap breast reconstruction can be safely and reliably performed also in selected patients with large ptotic breasts (15).

In order to cover and support the inferior aspect of the breast pocket and optimize aesthetic results, acellular dermal matrix (ADM) is increasingly being used in implant-based breast reconstruction; however, its use has not yet gained universal acceptance because of reported postoperative infection and seroma formation rates (16).

Controversial aspects

Nowadays, as quoted by Rusby et al. (17), the three main issues associated with NSM are oncological safety, nipple viability and aesthetic outcome.

Oncological safety

Routine removal of the nipple in mastectomies has been performed on the base of the risk of occult nipple involvement. Studies have shown that occult NAC involvement in BC patients with invasive carcinoma varies from 0% to 58% (18).

Parks (19), Jensen and Wellings (20) and Wellings (21) demonstrated that breast ductal and lobular cancer arises in terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs).

Stolier et al. (22) reviewed 32 nipple specimens obtained from mastectomy, detecting the presence of TDLUs in only 3 (9%) of the nipples examined and all TDLUs were located at the base of the papilla. No TDLUs were found in the tip of the nipple. Stolier’s results showed that the infrequent occurrence of TDLUs in the nipple papilla consequently renders the development of a primary cancer in this area unusual.

Vlajcic and colleagues (23) identified prognostic factors predictive of NAC involvement by cancer. According to their analysis, the NAC could be safely preserved with tumor size <2.5 cm and tumor-to-nipple distance >4 cm.

Larger tumours have higher rates of occult nipple malignancy: the overall incidence of nipple involvement in tumours smaller than 2 cm is 9.8%; 2 to 5 cm, 13.3%; and greater than 5 cm, 31.8% (24-26).

Simmons et al. (27) identified tumor location as a variable that reliably predicts nipple involvement. In their study, the overall frequency of nipple involvement was 10.6% (23 of 217 cases). When the tumor was located in central or retroareolar regions, the nipple was involved in 27.3%, when located in the other quadrants it was in 6.4%.

Kissin and Kark detected an higher nipple involvement in patients with central tumors located within 2 cm from the areolar margin and in women with four or more positive axillary nodes (28).

There is strong evidence to suggest that reduced tumor to nipple distance (<2 cm), lymph node metastasis, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), presence of an extensive intraductal component, HER2 amplification, multicentricity and retroareolar location increase the incidence of occult nipple malignancy (29).

Recently Caffrey et al. carried out the first study to evaluate whether pathological features on preoperative core biopsy could predict retroareolar involvement. Ninety-three cases of NSM with available biopsy slides were retrieved; the overall rate of retroareolar malignancy was 11.8% (11/93). They observed a correlation between preoperative identification of LVI on core biopsy and positive retroareolar margin and this should contribute significantly to surgical decision making in combination with current radiological and clinical criteria (30).

Patients undergoing mastectomy are usually those with the most extensive disease and attention to the oncological safety is paramount; namely, complete removal of the gland including the axillary tail must be warranted. Conservative mastectomies offer to the surgeons poorer exposure as compared to conventional mastectomy and consequently patients are at increased risk for close or positive margins with reported rates as high as 28.8-68.8% (31-33).

NSM is considered a safe option for women with BC and does not seem to increase recurrence or diminish survival. Loco-regional recurrence (LRR) rates in patients after NSM have proven to be equivalent to those seen with other procedures (34), and recurrence at the nipple is very rare (35).

In 2009, Gerber et al. (36) compared three groups of patients who underwent either modified radical mastectomy (MRM), skin sparing mastectomy (SSM), or NSM and provided almost 10 years of extended follow-up data. The overall local recurrence rates amounted to 10.4% (SSM), 11.7% (NSM) and 11.5% (MRM). There were no significant differences between subgroups and NSM was deemed an oncologically safe procedure.

Likewise, Kim and co-workers (37) noted no differences in local recurrence and overall survival comparing the same three groups of patients as Gerber, after a follow-up of 101 months.

Benediktsson and colleague (38) reported a series of 216 patients who underwent conservative mastectomy with a long follow-up (median 13 years). The 10-year frequency of LRR was 20.8% and they attributed this high rate to the lack of radiotherapy in many cases that later would have received it according to international guidelines. The LRR rate in irradiated patients was 8.5%.

At the European Institute of Oncology (39), from March 2002 to December 2007, 934 women underwent NSM: 772 patients with invasive carcinoma (group A) and 162 with intraepithelial neoplasm (group B). Median follow-up was of 50 months. In group A were reported 28 (3.6%) local recurrences in the breast at 5-year cumulative incidence and 6 (0.8%) were observed on the NAC. In group B 9 (4.9%) recurrences were noticed in the breast and 5 (2.9%) on the NAC. The 5-year overall survival was 95.5% for the invasive group and 96.4% for the total series of 934 patients. The LRR, distant recurrence and death rates reported in this study are consistent with the results of the literature after radical mastectomy or SSM.

Poruk et al. (40) performed a chart review on patients who underwent NSM compared to SSM for BC treatment and prophylaxis over a 6-year period evaluating the outcomes including recurrence and survival and they found no significant differences.

Low rate of local recurrence in most series, and 5-year survival rates of more than 95%, are reassuring for both patient and surgeons.

Nipple viability

Preservation of the blood supply to the nipple and areola is the most important concern during NSM. Nipple or areolar necrosis is a well described complication of this operation and presents an increased risk of implant loss (41).

The reported incidence of necrosis following NAC preservation ranges from 0 to 20 per cent in the literature, with higher rates in patients receiving radiation.

It is likely that nipple necrosis is influenced by patient factors and surgical technique. Komorowski et al. (42) showed that age over 45 years has a significant impact on the risk of necrosis and Garwood and co-workers (33) reported smoking to be a risk factor due to direct skin vasoconstrictor effects of nicotine.

Garwood et al. (33) also showed that incisions extending around more than 30 per cent of the areolar circumference are an independent risk factor for necrosis. They also investigated the impact of reconstruction type: immediate reconstruction with a fixed-volume implant may result in immediate tension on the skin flaps and thus affect the blood supply to the nipple causing nipple necrosis, so they increased the use of tissue expanders. The use of tissue expanders helps to reduce surgical complications preventing ischemia and necrosis of the preserved NAC through a progressive stretching of the skin.

In facts, viability of the NAC relies on preservation of the blood supply to the nipple, ducts, and the surrounding skin.

Rusby and colleagues (43) conducted a microanatomical study of nipple microvessels and their position relative to lactiferous ducts in 48 mastectomy specimens. The peripheral 2-mm layer of a non-irradiated nipple tissue was found to contain 50% of the blood vessels in cross-section, whereas 66% of the blood vessels were identified in 3-mm of the periphery. According to their study, leaving a peripheral rim of 2-mm of nipple skin and subcutaneous tissue resulted in complete excision of the duct bundle in 96% of cases, while a thicker peripheral rim of 3-mm would lead to complete excision in 87% of cases only, with a consequent higher risk of leaving residual duct tissue in place.

Stolier et al. (44) reported 82 consecutive cases of NSM in which a 2-mm rim of tissue was left in place at the tip of the nipple with no skin loss affecting the NAC.

When performing NSMs, Petit et al. (45) prefer to leave a 5-mm thick layer of tissue in place under the areola with the aim of preserving NAC microscopic circulation. However, such a procedure requires intra or post-operative radiotherapy to decrease the risk of local recurrences and this, in turn, exposes the nipple to ischaemic damages with an increased risk of NAC necrosis.

Nipple necrosis can be partial and does not always result in complete skin loss. Sacchini et al. (8) reported a nipple necrosis rate of 11%, but 59% of these cases involved less than one third of the nipple.

Van Deventer noted that the small vessels feeding the NAC are in turn fed by much larger vessels, the most prominent of which are the internal mammary artery (internal thoracic) and the lateral thoracic artery (46). Based on the work of van Deventer as well as Palmer and Taylor, it would appear that the 2nd intercostal perforator off the internal mammary artery is the main vessel supplying the NAC; it is the principal perforator in 85% of cases (47) and it should be spared whenever possible.

The 2nd intercostal perforator exits the pectoralis major muscle outside of the breast parenchyma and it is easily damaged as skin flaps are developed, therefore elevating skin flaps over the medial breast should be done carefully. This vessel can be also used for free flap vascularization. Other perforating vessels which emerge from the 3rd and 4th interspaces off the internal mammary artery are also important in NAC vascularization. Those that arise more medially into the substance of the breast are sacrificed to achieve complete breast removal.

It is likely that NAC necrosis cannot be entirely avoided. However, to limit these complications, the breast surgeon must pay attention to details and incisions must be planned to minimize vascular impairment to the skin and NAC. It could be helpful to carefully review breast imaging prior to surgery, not just to evaluate the extent of disease but also to help define the appropriate anatomic planes of dissection (48). In facts, patients expect not only adequate oncological outcomes but also good cosmetic results and, aside from the flap failure or loss of a synthetic implant, nothing affects the cosmetic outcome more than skin or nipple necrosis.

Cosmetic outcomes

It is generally accepted that NSM provides better cosmetic results than MRM and the importance of NAC preservation within the context of a woman’s body image has been addressed in several studies.

In a study by Gerber et al. (34), patients and surgeons evaluated aesthetic results of SSM versus NSM 12 months after surgery. Patients expressed similar satisfaction with SSM and NSM and most aesthetic outcomes were reported as good or excellent. However, the surgeons reported 74% of NSM as excellent result and 26% as good, while only 59% of SSM were rated excellent, 22% good, and 20% fair.

Didier et al. reported that patients expressed a very high level of satisfaction with nipple preservation and perceived NSM as helpful to better cope with the traumatic experience of BC and loss of a breast (49). Their study focused on patient satisfaction with body image, sexuality, cosmetic results, and psychological adjustment. Patients with NSM were more willing to see themselves or be seen naked, and had significantly lower ratings for feelings of mutilation. Patients who underwent NSM as compared to SSM reported significantly greater satisfaction with cosmetic results. NSM was judged good/excellent from 78.6% of patients, and 42.9% of them retained nipple sensation (50).

Adjuvant radiotherapy decreases the aesthetic results even after a long period of time; if the need for post-operative radiation therapy is known, a delayed reconstruction is preferable (36).

NSM has evolved as an oncologically safe technique to improve the overall quality of life for women providing excellent cosmetic outcomes. NSM grants a natural appearing nipple and enables the patient to have a truer sensation of having her own breast. In addition, the procedure spares the patient from operations associated with nipple reconstruction, decreasing the anxiety and costs.

Alternative surgical techniques

Many patients are not ideal candidates for NSM because of concerns about nipple-areolar viability. Significant large/ptotic breast (defined by location of the NAC below the infra-mammary crease and suprasternal notch to nipple distance of 26 cm or more), pre-existing breast scars and history of active cigarette smoking are considered risk factors to nipple necrosis following NSM (51).

In order to extend the benefits of nipple preservation to patients who are perceived to be at higher risk for nipple necrosis, a surgical delay procedure 7-21 days prior to mastectomy aimed at improving nipple viability was proposed by Jensen et al. (52).

The skin flap is elevated in the plane of a therapeutic mastectomy beneath the nipple-areolar complex and surrounding mastectomy skin, so that the surgical wound stimulates an improved blood supply to the areola; approximately 4-5 cm of surrounding skin is undermined (Figure 4).

The incision is vertical from the edge of the areola toward the infra-mammary crease or lateral to the NAC extending toward the axilla. Attention is paid to the concept of ‘‘degrees of perfusion’’ of the nipple areola complex (53). In patients who have had previous circumareolar or periareolar incisions, special attention is directed at maintaining the existing blood supply through the scar tissue by not using the previous incision around the NAC.

Alternatively, a ‘‘hemi-batwing’’ procedure can be performed in patients with breast ptosis; the skin within the hemi-batwing pattern remains undisturbed during the delay procedure and will be removed with the underlying breast gland at the time of mastectomy.

After this delay procedure, blood supply for the retained NAC is maintained for 360° of perfusion if a linear incision is chosen, or it is limited to 180° of perfusion through the inferior mastectomy flap if a hemi-batwing pattern is used.

Special attention is paid to the transection of the ducts connecting the breast gland to the nipple.

A 1-cm thick biopsy of this ductal tissue (directly beneath the nipple) is submitted for permanent section pathology. If it is positive for tumor the NAC is removed at the time of mastectomy. Similarly, sentinel node biopsy can be brought forward, and in case of positivity on permanent section, an axillary dissection can be made at the time of mastectomy, 7-21 days later according to the traditional technique.

Jensen et al. (52) performed the nipple-areolar delay procedure on 31 nipples and all of them survived.

Palmieri et al. (54) recruited 18 women with T1 cancer, 2.5 cm from the NAC and 1.5 cm from the skin and pectoralis fascia. The procedure was divided into two different phases: NAC vascular autonomization using local tumescent anesthesia with electrified laparoscopic scissor; and delayed nipple sparing modified subcutaneous mastectomy plus subpectoralis textured silicone breast implant 3 weeks later using general anesthesia. No NAC necrosis was observed.

The surgical delay is a safe, simple and effective technique used to enhance vascularization of the skin flaps and the NAC. The ischemic insult induced in the first stage surgery leads to hypertrophy of the vessels and/or the development of new blood vessels. This procedure performed 7-21 days before NSM allows safe preservation of the nipple-areolar-complex in patients who generally would not be considered candidates for NAC sparing mastectomy and it can provide a better planning of surgery (Figure 5).

Recently our group published a technical modification of NSM that is performed through an inverted-T mastopexy, designed with the purpose to allow nipple preservation in large and ptotic breasts (55). Sixteen procedures in 13 patients were performed, with no cases of complete necrosis requiring removal of NAC; however, this early experience has not yet received a formal outcome assessment.

The G.B. Morgagni hospital experience

The surgical technique we use for NSM (including immediate reconstruction) is similar to that described by Regolo et al. (9), Sacchini et al. (8) and Garwood et al. (33), and involves making an italic S incision that extends from the lateral edge of the areola to the external equatorial line, which also permits access to axillary lymph nodes. NAC isolation is performed by hydrodissection of the areola, as previously described (12).

Once mastectomy has been completed and the breast excised, a 3-5 mm thick layer of tissue is removed from the retroareolar area of the specimen and submitted for sub-areolar margin evaluation on frozen sections. If neoplastic tissue is detected, the NAC is removed and the procedure is converted to a SSM. All the retroareolar specimens undergo a definitive histological evaluation; if it confirms as negative for neoplasia we suggest follow up. If the definitive evaluation results positive we can consider the removal of NAC, radiotherapy or follow-up depending on histological examinations and patient preferences.

In a period between December 2006 and September 2014, in the Breast Surgery Unit of Morgagni hospital in Forlì, 252 NSM were planned: 53 (21%) procedures were converted to SSM because of intraoperative findings of cancer in retro areolar tissue and 199 (79%) NSM were performed. Histological examination of removed NACs showed the presence of 9 (17%) invasive cancer, 38 (72%) in situ carcinoma and 6 (11%) LIN III.

All the intraoperative biopsies of the retroareolar specimen were confirmed at the definitive histological evaluation.

Indications for surgery were risk reducing mastectomy (RRM) with prophylactic purpose in 23 cases (9.1%), in situ carcinoma in 83 (33%), invasive carcinoma in 127 (50.4%) and C5 pre-operative cytology in 19 (7.5%).

Among 178 patients (199 procedures) who underwent NSM and breast reconstruction, 21 had a bilateral procedure and 157 a monolateral one. Mean age of the patients was 49±8 (range, 27-74) years. The mean distance between the tumor and the nipple was 35 mm (SD: ±20; range: 5-80 mm). Multicentric tumour localization was detected in 71 cases.

We performed 168 intraoperative sentinel lymph node (SNL) biopsies and 25 of these were positive with subsequent axillary lymph node dissection (ALND).

The post operative histological reports showed 110 (55.2%) invasive cancer (DCI and LCI), 51 (25.6%) in situ carcinoma (DCIS and LCIS), 14 (7%) DIN-LIN, 7 (3.6%) other histotype and 17 (8.6%) absence of neoplasia. Median follow-up was 43 months (range, 2-94 months).

In our cases we had two immediate post-operative major complications, one case of infection of the prosthesis requiring its removal and one case of severe bleeding requiring re operation to evacuate the hematoma. No complete necrosis of the NAC was identified. We observed 25 partial transient ischemia of the NAC with epidermolysis, NAC dystopia in six patients, flattening of the nipple in nine, small size of the areola in four and retraction or lateral deviation of the NAC in two cases. Nipple sensitivity and erectile capacity of the nipple appeared insufficient in most of our patients. Baker grade IV capsular contracture was noticed in one patient and grade II or III in six. The capsular contracture was subsequent to radiotherapy in three cases and in those patients we performed lipofillings.

Local recurrence developed in one patient in the subcutaneous tissue corresponding to the former tumor site (upper inner quadrant), 14 months after the initial procedure. None of our patients had recurrences in the NAC after NSM. Distant metastasis occurred in six patients (3%); two in the bones, one in the lung, one in the axilla, one in the liver and one in the ovary.

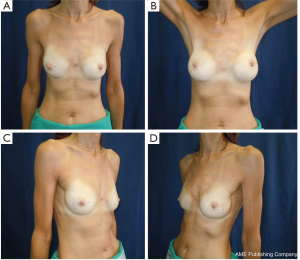

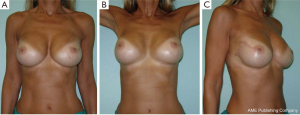

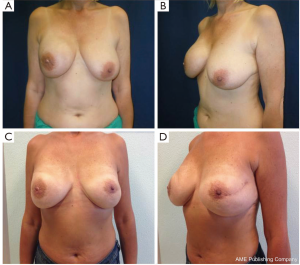

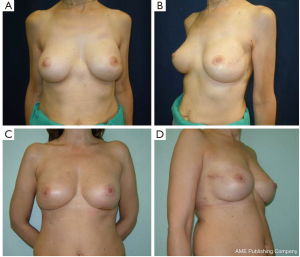

All our patients underwent immediate reconstruction with prosthesis or tissue expander, only a woman did not accept the prosthesis and we reconstructed her breast performing three lipofillings. Immediate reconstruction with subpectoral permanent implant was performed in 43 procedures (21.6%) and 156 (78.4%) were a two-stage reconstruction with a subpectoral tissue expander (Figure 6). The breast reconstruction has been completed with the second stage in 119 patients and 53 (68.9%) implant augmentation, 18 (23.4%) mastopexy, 5 (6.4%) mastopexy with prosthesis and 1 (1.3%) reductive mastoplasty were performed to obtain symmetry of the contralateral breast.

Overall aesthetic and functional results of the post-NSM reconstructed breasts were judged by the patients and surgeons as poor (1%), good (67%) and very good (32%) results (Figure 7). The morphology of the contralateral breasts was considered good (65%) and very good (35%). Level of satisfaction with cosmetic results was high at the end of the reconstruction process and similar between prophylactic and therapeutic procedures (Figure 8).

Conclusions

Nowadays NSM can be considered the best surgical option for BC treatment when the mastectomy becomes inevitable. NSM is also assessed as an elective indication in risk reduction mastectomy. This surgery allows for an excellent cosmetic results ensuring, at the same time, a correct and complete oncological radicality.

The preservation of the entire skin envelope makes this surgical procedure less traumatic from the psychological point of view of the patient and the reconstruction becomes better and more physiological. The commitment of the scientific community should aim to experiment and explore new surgical techniques that can extend the application of this procedure to an increasing number of patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Julie-Anne Smith for revising the manuscript.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Kaufmann M, Morrow M, von Minckwitz G, et al. Locoregional treatment of primary breast cancer: consensus recommendations from an International Expert Panel. Cancer 2010;116:1184-91. [PubMed]

- Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005;366:2087-106. [PubMed]

- Nava MB, Catanuto G, Pennati A, et al. Conservative mastectomies. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2009;33:681-6. [PubMed]

- Veronesi U, Stafyla V, Petit JY, et al. Conservative mastectomy: extending the idea of breast conservation. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e311-7. [PubMed]

- Rowland JH, Desmond KA, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Role of breast reconstructive surgery in physical and emotional outcomes among breast cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1422-9. Erratum in: J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:68. [PubMed]

- Chung AP, Sacchini V. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: where are we now? Surg Oncol 2008;17:261-6. [PubMed]

- Cataliotti L, Galimberti V, Mano MP. La “Nipple Sparing Mastectomy” (NSM). Attualità in senologia 2010;59:11-20.

- Sacchini V, Pinotti JA, Barros AC, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer and risk reduction: oncologic or technical problem? J Am Coll Surg 2006;203:704-14. [PubMed]

- Regolo L, Ballardini B, Gallarotti E, et al. Nipple sparing mastectomy: an innovative skin incision for an alternative approach. Breast 2008;17:8-11. [PubMed]

- Rawlani V, Fiuk J, Johnson SA, et al. The effect of incision choice on outcomes of nipple-sparing mastectomy reconstruction. Can J Plast Surg 2011;19:129-33. [PubMed]

- Harness JK, Vetter TS, Salibian AH. Areola and nipple-areola-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer treatment and risk reduction: report of an initial experience in a community hospital setting. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:917-22. [PubMed]

- Folli S, Curcio A, Buggi F, et al. Improved sub-areolar breast tissue removal in nipple-sparing mastectomy using hydrodissection. Breast 2012;21:190-3. [PubMed]

- Barnea Y, Cohen M, Weiss J, et al. Clinical confirmation that the nipple areola complex relies solely on the dermal plexus. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;101:2009-10. [PubMed]

- Tancredi A, Ciuffreda L, Petito L, et al. Nipple-areola-complex sparing mastectomy: five years of experience in a single centre. Updates Surg 2013;65:289-94. [PubMed]

- Schneider LF, Chen CM, Stolier AJ, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy and immediate free-flap reconstruction in the large ptotic breast. Ann Plast Surg 2012;69:425-8. [PubMed]

- Gunnarsson GL, Børsen-Koch M, Wamberg P, et al. How to perform a NAC sparing mastectomy using an ADM and an implant. Gland Surg 2014;3:252-7. [PubMed]

- Rusby JE, Smith BL, Gui GP. Nipple-sparing mastectomy. Br J Surg 2010;97:305-16. [PubMed]

- Cense HA, Rutgers EJ, Lopes Cardozo M, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy in breast cancer: a viable option? Eur J Surg Oncol 2001;27:521-6. [PubMed]

- Parks AG. The micro-anatomy of the breast. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1959;25:235-51. [PubMed]

- Wellings SR, Jensen HM. On the origin and progression of ductal carcinoma in the human breast. J Natl Cancer Inst 1973;50:1111-8. [PubMed]

- Wellings SR. A hypothesis of the origin of human breast cancer from the terminal ductal lobular unit. Pathol Res Pract 1980;166:515-35. [PubMed]

- Stolier AJ, Wang J. Terminal duct lobular units are scarce in the nipple: implications for prophylactic nipple-sparing mastectomy: terminal duct lobular units in the nipple. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:438-42. [PubMed]

- Vlajcic Z, Zic R, Stanec S, et al. Nipple-areola complex preservation: predictive factors of neoplastic nipple-areola complex invasion. Ann Plast Surg 2005;55:240-4. [PubMed]

- Smith J, Payne WS, Carney JA. Involvement of the nipple and areola in carcinoma of the breast. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1976;143:546-8. [PubMed]

- Wang J, Xiao X, Wang J, et al. Predictors of nipple-areolar complex involvement by breast carcinoma: histopathologic analysis of 787 consecutive therapeutic mastectomy specimens. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:1174-80. [PubMed]

- Wertheim U, Ozzello L. Neoplastic involvement of nipple and skin flap in carcinoma of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol 1980;4:543-9. [PubMed]

- Simmons RM, Brennan M, Christos P, et al. Analysis of nipple/areolar involvement with mastectomy: can the areola be preserved? Ann Surg Oncol 2002;9:165-8. [PubMed]

- Kissin MW, Kark AE. Nipple preservation during mastectomy. Br J Surg 1987;74:58-61. [PubMed]

- Mallon P, Feron JG, Couturaud B, et al. The role of nipple-sparing mastectomy in breast cancer: a comprehensive review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;131:969-84. [PubMed]

- Caffrey E, McDermott AM, Walsh J, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: can preoperative biopsy findings predict retroareolar margin involvement? Histopathology 2013;63:143-6. [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Montag E, Arruda E, et al. Immediate reconstruction following breast-conserving surgery: management of the positive surgical margins and influence on secondary reconstruction. Breast 2009;18:47-54. [PubMed]

- Carlson GW, Page A, Johnson E, et al. Local recurrence of ductal carcinoma in situ after skin-sparing mastectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:1074-8; discussion 1078-80. [PubMed]

- Garwood ER, Moore D, Ewing C, et al. Total skin-sparing mastectomy: complications and local recurrence rates in 2 cohorts of patients. Ann Surg 2009;249:26-32. [PubMed]

- Gerber B, Krause A, Reimer T, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy with conservation of the nipple-areola complex and autologous reconstruction is an oncologically safe procedure. Ann Surg 2003;238:120-7. [PubMed]

- Garcia-Etienne CA, Cody Iii HS. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: initial experience at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and a comprehensive review of literature. Breast J 2009;15:440-9. [PubMed]

- Gerber B, Krause A, Dieterich M, et al. The oncological safety of skin sparing mastectomy with conservation of the nipple-areola complex and autologous reconstruction: an extended follow-up study. Ann Surg 2009;249:461-8. [PubMed]

- Kim HJ, Park EH, Lim WS, et al. Nipple areola skin-sparing mastectomy with immediate transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap reconstruction is an oncologically safe procedure: a single center study. Ann Surg 2010;251:493-8. [PubMed]

- Benediktsson KP, Perbeck L. Survival in breast cancer after nipple-sparing subcutaneous mastectomy and immediate reconstruction with implants: a prospective trial with 13 years median follow-up in 216 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2008;34:143-8. [PubMed]

- Petit JY, Veronesi U, Orecchia R, et al. Risk factors associated with recurrence after nipple-sparing mastectomy for invasive and intraepithelial neoplasia. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2053-8. [PubMed]

- Poruk KE, Ying J, Chidester JR, et al. Breast cancer recurrence after nipple-sparing mastectomy: one institution's experience. Am J Surg 2015;209:212-7. [PubMed]

- Holzgreve W, Beller FK. Surgical complications and follow-up evaluation of 163 patients with subcutaneous mastectomy. Aesthetic Plast Surg 1987;11:45-8. [PubMed]

- Komorowski AL, Zanini V, Regolo L, et al. Necrotic complications after nipple- and areola-sparing mastectomy. World J Surg 2006;30:1410-3. [PubMed]

- Rusby JE, Brachtel EF, Taghian A, et al. George Peters Award. Microscopic anatomy within the nipple: implications for nipple-sparing mastectomy. Am J Surg 2007;194:433-7. [PubMed]

- Stolier AJ, Sullivan SK, Dellacroce FJ. Technical considerations in nipple-sparing mastectomy: 82 consecutive cases without necrosis. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:1341-7. [PubMed]

- Lohsiriwat V, Petit J. Nipple Sparing Mastectomy: from prophylactic to therapeutic standard. Gland Surg 2012;1:75-9. [PubMed]

- van Deventer PV. The blood supply to the nipple-areola complex of the human mammary gland. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2004;28:393-8. [PubMed]

- Palmer JH, Taylor GI. The vascular territories of the anterior chest wall. Br J Plast Surg 1986;39:287-99. [PubMed]

- Stolier AJ, Levine EA. Reducing the risk of nipple necrosis: technical observations in 340 nipple-sparing mastectomies. Breast J 2013;19:173-9. [PubMed]

- Didier F, Radice D, Gandini S, et al. Does nipple preservation in mastectomy improve satisfaction with cosmetic results, psychological adjustment, body image and sexuality? Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;118:623-33. [PubMed]

- Nahabedian MY, Tsangaris TN. Breast reconstruction following subcutaneous mastectomy for cancer: a critical appraisal of the nipple-areola complex. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:1083-90. [PubMed]

- Spear SL, Hannan CM, Willey SC, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;123:1665-73. [PubMed]

- Jensen JA, Lin JH, Kapoor N, et al. Surgical delay of the nipple-areolar complex: a powerful technique to maximize nipple viability following nipple-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:3171-6. [PubMed]

- Jensen JA, Orringer JS, Giuliano AE. Nipple-sparing mastectomy in 99 patients with a mean follow-up of 5 years. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:1665-70. [PubMed]

- Palmieri B, Baitchev G, Grappolini S, et al. Delayed nipple-sparing modified subcutaneous mastectomy: rationale and technique. Breast J 2005;11:173-8. [PubMed]

- Folli S, Mingozzi M, Curcio A, et al. Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy: An Alternative Technique for Large Ptotic Breasts. J Am Coll Surg 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]