Medical professionals’ knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses among breast cancer patients in China—a cross-sectional study

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors in women. In 2018, 367,900 new cases of breast cancer were recorded in women in China (1), and breast cancer accounts for 19.2% of all cancers in women (2). Due to the steady progress in the comprehensive diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer, the survival rate has continued to increase (3). Research has shown that one-third of female cancer survivors in Shanghai are breast cancer patients (4).

Surgery is still the most effective and main treatment strategy for curable breast cancer (5). In Western countries, breast-conserving surgery has accounted for more than 50% of breast cancer surgeries in recent years; however, unlike Western countries, China continues to focus on the use of modified mastectomy to treat breast cancer (6). The breasts are not vital organs that sustain life activities (7), however, they are an important organ in female sexuality. The loss of a breast can cause women to have negative physical and mental images of themselves (8), which in turn can have psychological effects, including feelings of fear, depression, inferiority and helplessness (9,10). Breast loss can significantly change a patient’s body posture (e.g., trunk, shoulder and waist asymmetry) (11). Further, it can also have strong negative effects on women’s feelings and self-esteem, and can result in a loss of confidence in their sexual lives and poor self-image (12,13).

For breast cancer patients who are unable or unwilling to undergo breast reconstruction surgery, external breast prostheses represent an ideal choice (14). In addition to addressing physical defects and improving the appearance, the wearing of breast prostheses can also protect wounds, prevent scoliosis related to long-term body imbalances, and raise the patients’ self-confidence, thus improving their quality of life (15). In Western countries, approximately 80% of women will wear an external breast prosthesis for some period following their mastectomy (16-18). According to researches in China, Chinese women have very limited knowledge of breast prostheses and the information channels from which such knowledge could be acquired (19). Further, only 25.4% of patients acquire the breast prostheses-related knowledge from medical professionals. This may be because medical professionals have insufficient knowledge of breast prostheses themselves or because publicity on this topic is insufficient and very little information about breast prostheses is provided to patients (20).

To date, very few studies have been conducted on the use of external breast prostheses among breast cancer patients in China. Further, there is very little evidence about medical professionals’ knowledge of breast prostheses. By investigating medical professionals’ knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses, this study sought to understand the status and gain evidences to provide them with precise education and knowledge that will ensure the continuous improvement of patients’ quality of life.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE Statement reporting checklist—cross-sectional studies and MDAR reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/gs-20-657).

Methods

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Scientific and Ethical Committee of the Shanghai Cancer Center, Fudan University (No. HL201503). And it was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection. The individuals discussed in this manuscript have given written informed consent to publish their data.

Study population

From January to March 2019, electronic questionnaires were distributed to 635 medical staffs from 24 provinces and municipalities across China. To be eligible to participate in this study, participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: be a medical professional engaged in the diagnosis and treatment of breast diseases.

Study methods

This study used questionnaires to investigate the knowledge of medical professionals’ on the use of external prostheses among breast cancer patients.

Research tools

The following research tools were used in this study:

- A demographic questionnaire that included questions about gender, age, level of education, professional title, position, number of years working and geographical region;

- A questionnaire about medical professionals’ knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses among breast cancer patients. This self-designed questionnaire comprised a total of 20 items, that were mainly directed at determining the channels by which patients gain knowledge of breast prostheses, the reasons patients choose to wear breast prostheses, the type and prices of breast prostheses, and the time at which and frequency with which patients wear breast prostheses. The questions also sought to determine medical professionals’ level of knowledge of breast prostheses, if they provide information about breast prostheses to others and if so, the frequency at which they do so.

Statistical analysis

SPSS18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to collate and analyze the data collected in this study. Means, standard deviations and percentages were used to describe the demographic information of medical professionals. The rank sum test of multiple independent samples (i.e., Kruskal Wallis test) was used to compare the knowledge of medical professionals about the use of external breast prostheses among breast cancer patients. The medical professionals’ knowledge was examined in relation to their age, level of education, professional title, position, number of years working years and geographical region.

Results

Baseline characteristics of medical professionals

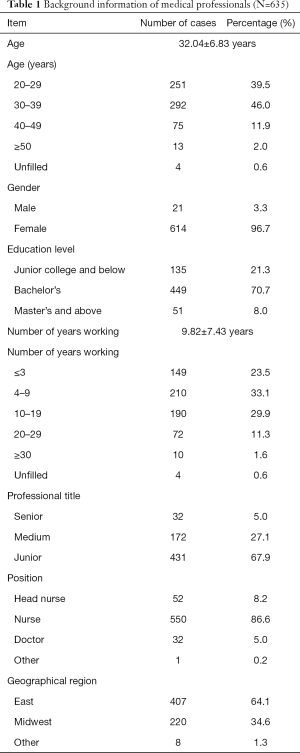

A total of 635 medical professionals participated in this study. Of the participants, 96.7% were female, 94.8% were nurses and 5% were doctors. The average age of the participants was 32.04 years old. The participants had worked 9.82 years on average. Of the participants, 70.7% held a bachelor’s degree and 8% held a master’s degree or above, 67.9% had junior titles, and 27.1% had intermediate titles. Of the participants, 64.1% were from East China and 34.6% were from Midwest China (Table 1).

Full table

Medical professionals’ knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses among breast cancer patients

Knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses among medical professionals of different ages

The younger the age, the more medical professionals would think patients were likely to choose direct-adhesive breast prostheses, and the more likely they were to think that wearing breast prostheses could improve their sexual lives. The older the age, the more likely medical professionals were to think that breast prostheses should be worn as soon as possible after surgery and at all times except when sleeping. Conversely, the older the age, the more medical professionals felt that they knew about breast prostheses, and the more frequently they provided breast prostheses-related information to patients, and the more they believed nurses needed to provide relevant information to patients (Table 2).

Full table

Knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses among medical professionals with different levels of education

Participants with higher levels of education had higher correct-answer rates in relation to the parts of the body that bear different types of breast prostheses and were more likely to believe that patients would accept more expensive breast prostheses. They were also more likely to think that it was better to wear breast prostheses as soon as possible after surgery and at all time except when sleeping, and that it was necessary for nurses to provide relevant information to patients (Table 3).

Full table

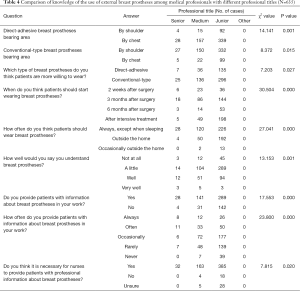

Knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses among medical professionals with different professional titles

Compared to participants with middle or senior titles, participants with junior titles were more likely to believe that patients were more willing to choose direct-adhesive breast prostheses. The higher the professional title, the sooner participants thought that breast prostheses could be worn after surgery. The higher the professional title, the greater the knowledge, medical professionals thought they had of breast prostheses. Participants with higher professional titles were also more likely to provide relevant information to patients and to do so with greater frequency, and they were also more likely to think that nurses should provide relevant information to patients (Table 4).

Full table

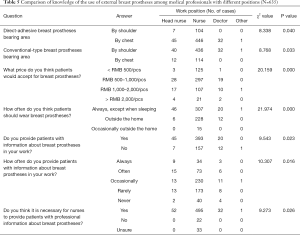

Knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses among medical professionals with different positions

Doctors and head nurses were more likely than nurses to believe that patients would accept more expensive breast prostheses. Compared to nurses and doctors, head nurses were more likely to think that breast prostheses should be worn at all times except when sleeping, and to provide information about breast prostheses to patients and to do so with higher frequency. Head nurses and doctors were more likely than nurses to think that nurses should provide information about breast prostheses to patients (Table 5).

Full table

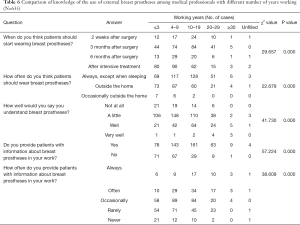

Knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses among medical professionals with different number of years working

The more years medical professionals had worked, the sooner they thought the breast prostheses could be worn after surgery. This finding was particularly prevalent among participants who had worked from 10 to 30 years. In relation to the medical professionals who had worked less than 30 years, the more years they had worked, the more likely they were to think that patients should wear breast prostheses at all times except when sleeping. The more years a medical professional had worked, the more they believed they knew about breast prostheses and the more likely they were to provide relevant information to patients, and to do so more frequently (Table 6).

Full table

Knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses among medical professionals from different geographical regions

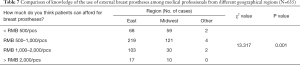

Compared with the medical professionals in Midwest China, those in East China were more likely to believe that patients would accept breast prostheses with higher prices (Table 7).

Full table

Discussion

Factors affecting medical professionals’ knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses

The use of external breast prostheses continues to develop. Breast prostheses are now available in different shapes, materials and designs (21), are becoming increasing easier to wear (22), and thus are better able to meet the needs of different patients. This study showed that medical professionals who are older in age, have higher levels of education, and have higher professional titles possess a greater knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses, and that doctors have a higher accuracy rate than nurses in providing professional information. As age and professional titles increase, medical professionals accumulate their knowledge in the professional field. In addition to acquiring basic professional information, medical professionals also have more professional experience. Individuals at this stage have a certain level of work and social experience, are more willing to keep improving in the professional field and are constantly absorbing professional knowledge. The higher the education level an individual has, the wider the scope of their knowledge and the more multiple access they have to relevant knowledge.

Studies on external breast prostheses in other countries have been more in-depth and detailed than those previously conducted in China (23-27). Thijs-Boer et al. (28) examined patients undergoing radical mastectomies in the Netherlands and found that modern women were concerned with the convenience of wearing breast prostheses, local skin stimulation, the protection of the wound surface and the degree to which the breast prostheses fit to their bodies. Thijs-Boer et al. (28) further found that women chose traditional breast prostheses or adhesive breast prostheses according to the above considerations. Kubon et al. (29) found that adhesive breast prostheses have significant advantages in terms of comfort, aesthetics and psychological perceptions.

However, as stated above, there is a lack of research on external breast prostheses in China. Most patients, and even some medical professionals are only aware of natural breast prostheses, that can be placed in the bra for use and know very little about direct-adhesive breast prostheses. The results of this study showed that younger medical professionals and those with lower professional titles were more likely to believe that patients would choose direct- adhesive breast prostheses. This may be because young people are more willing to learn new things and accept new forms of knowledge. The latest research shows that customized breast prostheses can be designed by using biological simulation technology (30).

Knowledge of different medical professionals as to the time at which and frequency with which external breast prostheses should be worn

Of the medical professionals that participated in this study, those who were older, those who had higher levels of education and those who had higher professional titles were more likely to think that external breast prostheses could be worn soon after surgery, and should be worn except when sleeping. The medical professionals who had worked in the field for a number of years (albeit less than 30 years) held similar views. Conversely, medical professionals who were younger, those who had lower levels of education, and those who had lower professional titles, were more conservative, and were of the view that patients should not wear breast prostheses until after intensive treatment and only needed to wear breast prostheses when undertaking outdoor activities.

Presently, no consensus has been reached as to when patients should first commence wearing external breast prostheses or the frequency with which they should do so. In developed Western countries, hospitals provide breast cancer patients with transitional breast prostheses after surgery, and specialist nurse advise patients on which breast prostheses are suitable based on each patient’s treatment and conditions. This is done to improve women’s self-esteem and self-confidence, and to enable women to continue engaging in their normal daily activities. Some domestic scholars are of the view that breast prostheses can be worn 4–6 weeks after surgery, however, breast prostheses should be selected and worn according to each individual’s wounds and conditions (31). Older medical professionals with higher levels of education and higher professional titles are more willing to acquire relevant professional information and also rely on their own professional experience in providing advice to patients.

Price is an important factor affecting patients’ decision to use external breast prostheses

The result of this study showed that individuals with higher levels of education and doctors, head nurses, and medical professionals from East China were more likely to believe that patients would accept external breast prostheses that are high in price. Chinese scholars have found that the following factors affect the use of external breast prostheses: (I) reconstruction surgery; (II) comfort level; (III) appearance and occasions; (IV) price; (V) psychological factors; and (VI) supporting information (32). In foreign countries, the costs associated with breast prostheses and the affiliated products are largely covered by medical insurance (33). However, in China, breast prostheses are not used as medical materials in hospitals and are not covered by medical insurance, which places an economic burden on some patients. As the eastern region of China is relatively economically developed, medical staffs are more ready to believe that patients could accept that new items have high prices than those in the middle and western regions.

Medical professionals, especially nurses, play an important role in educating patients on the use of external breast prostheses

Older medical professionals with higher levels of education level, and higher professional titles and head nurses were more likely to think that nurses should provide breast prostheses-related information to patients. The professional information currently being provided to patients about breast prostheses in China is insufficient. The lack of information is related to the decrease in the use of frequency of external breast prostheses (34,35). If sufficient information was available, patients’ level of satisfaction would be enhanced and the influence of false information could be eliminated (34).

Patients are unwilling to wear external breast prostheses for a variety of reasons, including that they do not fully understand the function of breast prostheses and are unable to access information on this subject (31). Patients often express that they want to get information from professional medical professionals, and nurses are viewed as one of the most important sources of information. Specialist breast nurses can actively provide patients with relevant information about their daily care, discuss the advantages and disadvantages, and provide personalized information to help patients address the psychosomatic and social effects associated with breast loss. Nurses should be sufficiently familiar with information and resources related to external breast prostheses, and be able to provide education and support to patients and to make referrals. Breast prostheses can never completely replace the lost breasts, however, appropriate breast prostheses can help patients to adapt to cancer diagnoses and the associated changes in their bodies and minds. It could also prevent long-term complications, such as shoulder droop, and ultimately improve the quality of life of patients. Professional nurses should evaluate patients’ breast prostheses every 2 years to address any changes in breast tissue or body shape caused by treatment or age (36-38).

Limitations of the study

This study has a number of limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional investigation; future studies should seek to conduct in-depth interviews with health professionals to learn more about their knowledge of external breast prostheses. Notably, the sample size of the study was not large given the population in China. Finally, experimental trials should be designed to examine external breast prostheses in the future.

Conclusions

As the replicas of real breasts, external breast prostheses can improve women’s self-esteem and self-confidence, and restore women’s social credibility and sense of belonging. Presently, there is a lack of information about the use of external breast prostheses among Chinese patients, and medical professionals’ knowledge of the use of external breast prostheses is also poor. Medical professionals, especially specialist breast nurses, can provide patients with comprehensive and educational information about the use of breast prostheses, assist patients in choosing appropriate external breast prostheses, understand patients’ wearing experiences, and help to reduce patients’ physical and mental distress.

Acknowledgments

We thank the support of hospital-level fund by Shanghai Cancer Center (HL201503) and we thank all medical professionals in this investigation.

Funding: Hospital-level fund by Shanghai Cancer Center (HL201503).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE Statement reporting checklist—cross-sectional studies and MDAR reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/gs-20-657

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/gs-20-657

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/gs-20-657). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was approved by the Scientific and Ethical Committee of the Shanghai Cancer Center, Fudan University (No. HL201503). And it was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection. The individuals discussed in this manuscript have given written informed consent to publish their data.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2018. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today.

- Feng RM, Zong YN, Cao SM, et al. Current cancer situation in China: good or bad news from the 2018 Global Cancer Statistics? Cancer Commun (Lond) 2019;39:22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zeng H, Chen W, Zheng R, et al. Changing cancer survival in China during 2003-15: a pooled analysis of 17 population-based cancer registries. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e555-e567. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng Y, Wu C, Zhang M. The epidemic and characteristics of female breast cancer in China. China Oncology 2013;23:561-9.

- Duan X. Review and enlightenment of 100 years history of breast cancer surgical treatment. Chinese Journal of Practical Surgery 2018;38:1227-31.

- Zuo W, Yang L. Several problems concerning the standardized implementation of breast-conserving surgery for breast cancer. Chinese Journal of Practical Surgery 2015;35:773-6.

- Yan X. A comparative analysis of the short-term effects of breast-conserving surgery and radical surgery on patients with early stage breast cancer. Electronic Journal of Clinical Medical Literature 2019;6:27-8.

- Zhang Y, Qu H, Hu H, et al. Effect of different surgical methods on quality of life of premenopausal breast cancer patients. Chinese Journal of General Surgery 2016;25:761-3.

- Berhili S, Ouabdelmoumen A, Sbai A, et al. Radical mastectomy increases psychological distress in young breast cancer patients: results of a cross-sectional study. Clin Breast Cancer 2019;19:e160-e165. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Izydorczyk B, Kwapniewska A, Lizinczyk S, et al. Psychological resilience as a protective factor for the body image in post-mastectomy women with breast cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1181. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ciesla S, Polom K. The effect of immediate breast reconstruction with Becker-25 Prosthesis on the preservation of proper body posture in patients after mastectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010;36:625-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ren H, Jia X, Wang Q. Correlation between postoperative self-image and coping style of patients with breast cancer. Chinese Journal of Modern Nursing 2014;11:1274-7.

- Qiu J, Li P. Investigation on the status of postoperative sexual life of breast cancer patients and its influencing factors. Chinese General Practice Nursing 2015;18:1783-5.

- Zhang H. Analysis of factors influencing the quality of life of postoperative breast cancer patients. Nursing Journal of Chinese People’s Liberation Army 2007;3:45-6.

- Huang L, Xiong B. Application of quality nursing service in wearing external breast prostheses for breast cancer patients after surgery. Journal of Yangtze University (Natural Science Edition) 2013;2:42-3.

- Roberts S, Livingston P, White V, et al. External breast prosthesis use: experiences and views of women with breast cancer, breast care nurses, and prosthesis fitters. Cancer Nurs 2003;26:179-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fitch MI, McAndrew A, Harris A, et al. Perspectives of women about external breast prostheses. Can Oncol Nurs J 2012;22:162-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borghesan DHP, Gravena AAF, Lopes TCR, et al. Variables that affect the satisfaction of Brazilian women with external breast prostheses after mastectomy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:9631-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Zhu D, Ruan H, et al. Psychological effect and nursing intervention of wearing artificial breast on patients with breast loss after breast cancer surgery. China Foreign Medical Treatment 2009;12:127-8.

- Sun L. Cognitive investigation on wearing breast external prostheses in patients with breast loss after breast cancer surgery. Journal of Qilu Nursing 2010;21:48-9.

- Liang H, Li J. Research on the evolution of bra shape and design trend abroad in the 20th century. Fashion Guide 2015;2:66-70.

- Luo H, Liu C. Research and analysis on the modeling design of artificial breast bra. Tianjin Textile Science & Technology 2018;5:8-11.

- Manikowska F, Ozga-Majchrzak O, Hojan K. The weight of an external breast prosthesis as a factor for body balance in women who have undergone mastectomy. Homo 2019;70:269-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Livingston PM, White VM, Roberts SB, et al. Women’s satisfaction with their breast prosthesis: What determines a quality prosthesis? Eval Rev 2005;29:65-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramu D, Ramesh RS, Manjunath S, et al. Pattern of external breast prosthesis use by post mastectomy breast cancer patients in India: descriptive study from Tertiary Care Centre. Indian J Surg Oncol 2015;6:374-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hojan K, Manikowska F. Can the Weight of an external breast prosthesis Influence trunk biomechanics during functional movement in postmastectomy women? Biomed Res Int 2017;2017:9867694. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGhee DE, Mikilewicz KL, Steele JR. Effect of external breast prosthesis mass on bra strap loading and discomfort in women with a unilateral mastectomy. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2020;73:86-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thijs-Boer FM, Thijs FJ, van de Wiel HB. Conventional or adhesive external breast prosthesis? A prospective study of the patients’ preference after mastectomy. Cancer Nurs 2001;24:227-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kubon TM, McClennen J, Fitch MI, et al. A mixed-methods cohort study to determine perceived patient benefit in providing custom breast prostheses. Current Oncology 2012;19:e43-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cruz P, Hernandez FJ, Zuniga ML, et al. A biomimetic approach for designing a full external breast prosthesis: post-mastectomy. Appl Sci 2018;8:357. [Crossref]

- Li Y, Zhang H, Zhao X. Investigation on the status of breast cancer patients wearing external prostheses after operation and analysis of influencing factors. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2016;15:56-8.

- Liang Y, Xu B. Factors influencing utilization and satisfaction with external breast prosthesis in patients with mastectomy: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Science 2015;2:218-24. [Crossref]

- Livingston PM, White V, Roberts S, et al. Access to breast prostheses via a government-funded service in Victoria, Australia. Experience of women and service providers. Eval Rev 2003;27:563-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gallagher P, Buckmaster A, O’Carroll S, et al. Experiences in the provision, fitting and supply of external breast prostheses: findings from a national survey. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2009;18:556-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gallagher P, Buckmaster A, O’Carroll S, et al. External breast prostheses in post-mastectomy care: women’s qualitative accounts. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19:61-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mahon SM, Casey M. Patient education for women being fitted for breast prostheses. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2003;7:194-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shenoy VK, Bangera BS, Pinto VM, et al. Rehabilitation of unilateral mastectomy using a hollow breast prosthesis: A clinical case report. J Cancer Res Ther 2019;15:1181-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hojan K. Does the weight of an external breast prosthesis play an important role for women who undergone mastectomy? Rep Pract Oncol Radiother 2020;25:574-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]