Oncoplastic breast surgery: indications, techniques and perspectives

Introduction

Breast-conservation surgery (BCS) is established as a safe option for most women with early breast cancer (1). In fact, the 5-year survival of BCS with radiation is not statistically different when compared with mastectomy alone in patients with Stage I or II breast cancer (2). Habitually, these procedures include quadrantectomy and lumpectomy. In quadrantectomy, a wide excision is usually performed, including skin and underlying muscle fascia. In lumpectomy, the objective is tumor excision without skin ressection and with negative surgical margins (2).

In spite of the acceptance that most BCS defects can be managed with primary closure, the aesthetic outcome may be unpredictable and frequently achieve an unsatisfactory outcome (2-10). In fact, approximately 10% to 30% of patients submitted to BCS are not satisfied with the aesthetic outcome. The main reasons are related to the tumour resection which can produce assymetry, retraction, and volume changes in the breast. In addition, radiation can also have a negative effect on the native breast. The main clinical aspects are related to skin pigmentation changes, telangiectasia, and skin fibrosis. In the glandular tissue, local radiation causes fibrosis and retraction (2,6).

Recently, increasing attention has been focused on oncoplastic procedures since the immediate aplication of plastic breast surgery techniques provide a wider local excision while still achieving the goals of a better breast shape and symmetry (6-18). In fact, the modern oncoplastic breast surgery combines principles of oncologic and plastic surgery techniques to obtain oncologically sound and aesthetically pleasing results. Thus, by means of customized techniques the surgeon ensures that oncologic principles are not jeopardized while meeting the needs of the patient from an aesthetic point of view (3).

In general, the oncoplastic techniques are related to volume displacement or replacement procedures and sometimes include contra-lateral breast surgery. Among the procedures available, local flaps, latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap and reduction mammaplasty/masthopexy techniques are the most commonly employed (11). Additionally, oncoplastic approach may begin at the time of BCS (immediate), weeks (delayed-immediate) or months to years afterwards (delayed). Regardless of the fact that there is no consensus concerning the best approach, the criteria are determined by the surgeon’s experience and the size of the defect in relation to the size of the remaining breast (9-11). The main advantages of the technique utilized should include reproducibility, low interference with the oncologic treatment and long-term results. Probably, all these goals are not achieved by any single procedure and each technique has advantages and limitations (11).

Indications

Timing

Surgical planning and timing of reconstruction should include breast volume, tumor location, the extent of glandular tissue resected, enabling each patient to receive an individual “custom-made” reconstruction. With immediate oncoplastic approach, the surgical process is smooth since oncological and reconstructive surgery can be associated in one operative setting. Additionally, because there is no scar and fibrosis tissue, breast reshaping is easier, and the aesthetic is improved (6,8,9,11,12,19). In fact, Papp et al. (12) observed that the aesthetic results showed a higher success rate in the immediate group when compared with delayed reconstruction patients. Similarly, Kronowitz et al. (9) observed that immediate repair is preferable to delayed because of a decreased incidence of complications. In our previous experience utilizing reduction mammaplasty techniques for BCS reconstruction, we observe that our post-radiation complication rate (delayed BCS reconstruction) was higher than that expected for mammaplasty without radiotherapy (20). After adjusting for other risk factors, the probability of complications tends to be higher for delayed reconstruction group. This finding is similar to published reports that suggest that delayed BCS reconstruction has a significantly higher complication rate compared with immediate procedures (8,9).

In terms of oncological benefits and adjuvant treatment, immediate oncoplastic reconstruction can be advantageous. Some clinical series have observed that patients with large volume breasts present more radiation related complications than patients with normal volume breasts (21-23). Additionally, some authors suggested that there is an increased fat content in large breasts, and the fatty tissue results in more fibrosis after radiotherapy than glandular tissue. Thus, Gray et al. (23), in a clinical series, observed that there was more retraction and asymmetry in the large-breasted versus the small-breasted group. Thus, breast reduction can increase the eligibility of large-breasted patients for BCS since it can reduce the difficulty of providing radiation therapy (15-17,21,24).

Another aspect is the possibility of accomplishing negative resection margin. In fact, the immediate reconstruction allows for wider local tumor excision, potentially reducing the incidence of margin involvement (15-17,24,25). Kaur et al. (25) compared patients submitted to oncoplastic procedures and to BCS. The oncoplastic approaches permitted larger resections, with a superior mean volume of the specimen and negative margins.

In spite of the benefits, the immediate reconstruction presents limitations. The surgical time can be lengthened, it can be time consuming, and require specialist training to learn and properly apply these procedures (2,3,15). Thus, delayed reconstruction can be advantageous in some specific group of patients. In fact, in some cases the final contour of the breast cannot be predicted at the time of the BCS (24). In addition, it is well accepted that radiation usually involves some degree of fibrosis and shrinkage. Some authors observed that although the aesthetic outcome can be satisfactory, the appearance of the radiated breast is occasionally less pleasing than the nonradiated one (5-8,24). Thus, in delayed reconstruction the plastic surgeon waits until the postoperative changes in the deformed breast stabilize. Another important point is related to the postoperative recovery. In theory some complications of the immediate reconstructions can unfavorably defer the adjuvant therapy. With delayed oncoplastic reconstruction, operative time is shorthened and the surgical process is less extensive than an immediate. However, our previous experience (11,14-17), and of others (8,18,24), has shown that immediate reconstruction does not compromise the start of radio and chemotherapy in the overall treatment of breast cancer.

Partial breast defects classification

Several classification schemes have been developed to characterize breast deformity and proposed reconstructive techniques (2,7-9,26-30). It has been our impression that a number of classifications have been described involving primary closure, breast reshaping, local and distant flaps, yet some of these techniques address late repair. Some of them are related to delayed reconstruction based on tissue deficiency and the presence of radiotherapy effects. Additionally, most articles include them within a broader category of complex breast defects and up to now, there are few clinical series that describe a systematic approach or propose an algorithm for reconstruction on an immediate basis.

In delayed reconstructions (29,30), Clough et al. classified the breast defects and oncoplastic procedures according to the response to reconstruction (30). Thus, patients with a type-I breast deformity have a normal-appearing breast with no deformity. However, there is asymmetry in the volume or shape between breasts and were managed by a contralateral breast surgery. Type-II patients have deformed breasts, however, is treated by an ipsilateral breast surgery or flap reconstruction. Type-III patients have either major deformity with fibrosis and were treated with total mastectomy and reconstruction.

Berrino et al. emphasized the importance of analyzing the etiology of the breast defect (29). In type I, the breast defect results from fibrosis and scar contracture. In type II, there is a localized deficiency of tissue including skin, or breast tissue, or both). Type III has a more advanced breast retraction with normal overlying skin. This is most frequently secondary to radiation in patients with large and grade III-IV of ptosis. Lastly, type-IV defects results from severe distortion and assymetry. There is significant breast tissue retraction, and the skin has local radiation-induced changes.

Recently, Hamdi et al. proposed a classification based on the size and location of the expected tumor resection and the ratio of breast volume to resection volume (2). Tumors involving the lower pole are most treated because this region is removed during most reduction mammaplasty. Other regions of tumor resection, can also be repaired using a combination of mammaplasty and glandular flaps to fill the breast defect. According to Hamdi’s classification one of the relative contraindications for rearrangement breast surgery (glandular flaps and reduction mammaplasty) is a large tumor/breast ratio (2). Thus, smaller breasts require different methods of reconstruction and a large-volume tumor resection, the recruitment of local flaps is required. A small lateral defect can reconstructed with a skin rotation flap or lateral thoracic axial skin flap. If these flaps become unavailable due to axillary lymph-node dissection, the lateral breast defects can be reconstructed using a flap based on the thoracodorsal system. The latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap is the most commonly used, however it is possible to use a similar skin paddle raised on perforators either from the thoracodorsal (TDAP) or intercostals vessels. In fact, the authors reported the use of the lateral intercostal artery perforator (LICAP) in BCS reconstruction within a clinical algorithm based on the location of the defect and the availability of these perforators. Both flaps are good alternative for lateral and inferior breast defects, however, the TDAP has a longer pedicle, thus enabling the flap to reach most of the breast. Medial defects are more complex to repair. In small lower-pole defects an epigastric rotation flap can be utilized, however, donor-site closure may distort the inframammary fold (IMF) contour once this flap is based on tissue directly below this anatomic area.

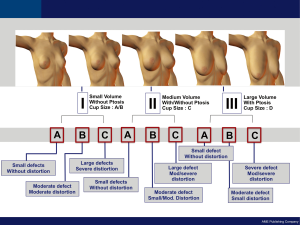

On the basis of our 15-year experience, it is possible to identify trends in types of breast defects and to develop an algorithm for immediate BCS reconstruction on the basis of the initial breast volume, the extent/location of glandular tissue ressection and the remaining available breast tissue (11). Each defect has its own special reconstructive necessities varying expectations for aesthetic outcome. To make possible development of a BCS reconstructive algorithm, immediate partial breast defects are classified into one of three types (Figure 1).

Type I

Defects include tissue resection in smaller breast without ptosis. Type IA defects involve minimal defects that do not cause volume alteration/distortion in the breast shape and the tissue ressected is less than 10-15 percent of the total breast volume. Initial tumor exposure is achieved through a periareolar approach in cases where the tumor is locately deeply. In patients where the tumor is located close to the skin, a separate incision is planned directly over the region to be ressected. Type IB defects involve moderate defects that do originate moderate volume alteration/distortion in the breast shape or symmetry and the tissue ressected is between 15 and 40 percent of the total volume. Usually, the skin above the tumor is ressected with the tumor. Type IC defects involve large defects that do cause significant volume alteration/distortion in the breast shape and symetry and the tissue ressected is more than 40 percent of the total breast volume.

Type II

This group includes tissue resection in medium sized breasts with/without ptosis. Type IIA involves small defects that do not cause enough volume alteration/distortion in the breast shape. Type IIB defects involve moderate defects that cause minor/moderate volume alteration in the breast shape. Type IIC defects involve large defects that cause moderate/large volume variations in the breast shape and symmetry.

Type III

This group includes tissue resection in large sized breasts with ptosis. Type IIIA involves small defects that do not cause enough aesthetic deformity. Type IIIB defects involve moderate defects that originate minor/moderate volume alterations in the breast shape or symmetry. Type IIIC defects involve large defects that cause significant volume alteration in the breast.

Oncoplastic techniques

Partial breast defects represent an anatomic variety that ranges from small defects that may repair with primary closure and to large defects that involve skin, NAC and a significant amount of glandular tissue. It has been our impression that a number of procedures have been described involving primary closure, breast reshaping, local and distant flaps, yet some of these techniques address late repair (11). In addition, some classifications have been described to evaluate the extent of resection, which has consequently created wide-range of surgical options with different indications (7-9,26-28). We believe that an algorithm gives the surgeon guidelines for management of immediate BCS defects. Partial mastectomy defects can be scored and classified according to the proposed classification. The application of this system to the spectrum of cases demonstrated that the algorithm works well and classifies patients in a useful system. Surgical planning should include the breast volume, tumor location, the extent of glandular tissue resected, and chiefly addressing individual reconstructive requirements, enabling each patient to receive an individual “custom-made” reconstruction. Evaluation of BCS reconstruction must subsequently consider these important points and, only then should the proper technique or a combination of procedures be chosen. In our experience, the majority of reconstruction techniques are performed with one of six surgical options: breast tissue advancement flaps (BAF), lateral thoracodorsal flap (LTDF), bilateral mastopexy (BM), bilateral reduction mammaplasty (BRM), latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap (LDMF) and abdominal flaps. Concerning the use of distant flaps (pedicled and free) in CBS reconstruction, there is no consensus about the indication and the more appropriate technique. In terms of benefits and morbidity, the abdominal wall area as donor site has some positive aspects. In fact, it has been our experience that the abdominal area provides the ideal volume for a partial and total breast reconstruction, even in large-breasts patients or in patients who undergo bilateral mastectomy. Thus, it is possible to utilize the mono-pedicled or bipedicled TRAM flap in CBS reconstruction. The establishment of microsurgery techniques led to the development of the free TRAM flap because of its increased vascularity and decreased rectus abdominis resection. Recently, the muscle-sparing free TRAM, DIEP, and SIEA flap techniques followed in an effort to reduce donor site morbidity by decreasing damage to the rectus abdominis muscle and fascia. However, a significant number of patients with positive postoperative tumor margins after immediate CBS reconstruction underwent a completion mastectomy with immediate abdominal flap breast reconstruction (31). This observation demonstrates the importance of not using the abdominal area (TRAM, DIEP or SIEA flaps) for immediate CBS reconstruction. In addition, our experience indicate that the great part of patients who develop a local recurrence and have a completion mastectomy will desire breast reconstruction with a abdominal flap. Again, and similar as pointed out by other authors (2,9), this stresses the importance of preservation of reconstructive options, especially the abdominal wall area.

Surgical planning should include breast characteristics, extent of breast tissue resected, and chiefly addressing individual reconstructive requirements. Additionally, the decision is usually determined by the surgeon’s preferences and the size of the defect in relation to the size of the remaining breast. In fact, it is important to identify trends in types of breast defects on the basis of the initial breast volume, the extent/location of glandular tissue ressection and the remaining available breast tissue.

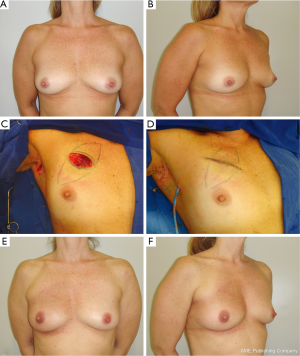

Types IA, IIA and IIIA

Defects are usually repaired with BAF in which the defect created is usually spherical or rectangular. The breast tissue is advanced along the chest wall or beneath the breast skin flap to fill the tumor defect. In order to achieve a better aesthetic outcome without significant skin retraction, superficial undermining between the breast tissue and the skin flap can be performed, preserving the skin blood supply. In the situation of simultaneous superficial and deeper undermining of the breast tissue, the blood supply of the BAF can be decreased, especially in obese patients with fatty breasts. Thus, care must be taken in this group of patients in order to avoid late fat necrosis. Usually, in these patients no contralateral breast procedure is performed (Figure 2).

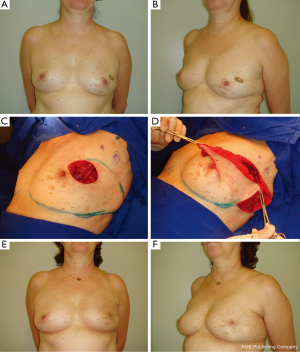

Type IB

In patients with lateral defects the LTDF is performed. Previously described elsewhere (14), this local flap is planned as a wedge-shaped triangle located entirely on the lateral aspect of the thorax and then rotated to the lateral breast defect. Introduced as a fasciocutaneous flap, the LTDF is a well-described technique for delayed breast reconstruction following radical surgery (32). In conservative breast surgery, Clough et al. (30) utilized the subaxillary area as a transposition flap with satisfactory results in lateral breast defects. According to the authors, if the defect is located in the superior pole of the breast, a superiorly based flap can be applied with the same principles. Similarly, Kroll et al. (33) transferred the subaxillary skin and subcutaneous fat as a composite and rotation flap to reconstruct a lateral breast defect. Although additional scars are created, they will be placed in the lateral region and therefore will not interfere with the wearing of clothing. In our experience, raising the LTDF provides a very wide access to the axilla which greatly facilitate lymph node dissection which was performed without excessive traction or injury to the structures in the axilla. When indicated the glandular tissue is dissected of the pectoral muscle in order to improve and reshaping of the breast. The defect margins are sutured to the margins of the flap and the donor site is closed primarily in layers (Figure 3). In patients with central and medial tumors, the LDMF can be utilized (11,13). The flap is designed into a horizontal position and the width of the paddle is measured according to the skin previously resected. The inferior and superior flap extension is subjectively estimated to match the volume of glandular tissue removed. Local flaps and specially the LTDF are useful techniques for upper outer or lower outer defects. Using tissue next to defect will provide matching color and texture to the breast. The technique provides wide access to the axilla when the flap incision is made in continuity with that of axillary incision.

In our previous experience, the LDMF is used to replace skin and glandular tissue resected during oncologic surgery (13). It is frequently indicated for severe defects where there is not enough breast tissue to perform the reconstruction. In addition, the most common use for BCS reconstruction has been in patients who underwent extensive breast tissue resection because of large tumors or compromised breast margins (13,34). These included patients with small or medium-volume breasts without ptosis that precludes the use of mammaplasty techniques. Comparing the LTDF with LDMF, local flaps are easy to perform, less time consuming, no special positioning, and no loss of muscle function (11). Additionally, LTDF when used as alternative to LDMF will spare the muscle as a potential reserve for future use in case of local recurrence.

Type IC

Defects are converted to a skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) and reconstructed with an apropriate technique. In patients with enough abdominal tissue, an abdominal flap (pedicled/free TRAM or DIEP) can be an option according to the surgeon’s preference. In patients without an adequate abdomen, a LDMF associated with an implant can be performed.

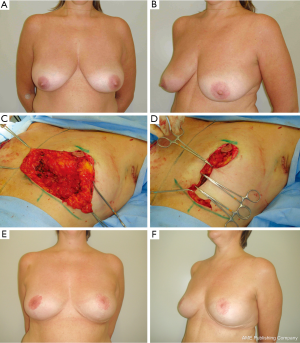

Type IIB

Defects are frequently reconstructed with BM techniques when there is sufficient breast tissue to perform the reconstruction. It has been our experience that BM for BCS reconstruction have aesthetic, functional and oncological advantages (15-17,19). The preoperative appearance can be improved, having smaller and more proportional breasts. Patients can obtain potentially less back and shoulder pain and the bilateral procedure allows us to examine the contralateral breast tissue for occult breast lesions (15,35). In terms of local control and adjuvant therapy, the added removal of a substantial volume of breast tissue could add a significant amount of safety in terms of surgical margins (24,25). In addition, the technique reduces the difficulty of providing radiation therapy to the remained breast tissues with acceptably low complication rates (21-23).

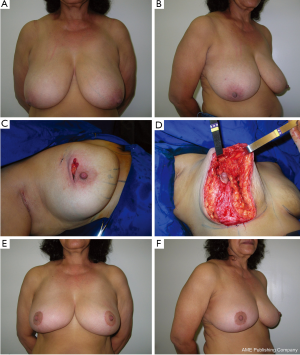

In previous reports (15,18), there is no consensus regarding the best BM technique for immediate BCS reconstruction. Possibly an ideal procedure does not exist and each case should be planned individually. The main advantages of the BM technique utilized should include reproducibility, safety and long-term results. As any surgical technique, all these goals are probably not met by any single procedure and it is supported by the large number of RM techniques available (15,36,37). Each presents particular advantages for their indications, tumor location limitations, vascular pedicle, additional skin and glandular resections due to compromised margins, and resultant scar. Because of rich breast tissue vascularization, the majority of techniques have based their planning on preserving the pedicle of the NAC after tumor removal. For tumors located in the lower region, the tumor resection can be incorporated into the sector of breast tissue removed as part of a superior pedicle mammaplasty (15,16). For upper region tumors, the lower breast tissue may be moved into the defect as a glandular flap and an inferior pedicle mammaplasty can be utilized (17). For inner and outer region tumors, the reduction pattern can be rotated and a superior-lateral or a superior-medial pedicle mammaplasty can be done (15) (Figure 4). The opposite breast surgery is usually performed to match the appropriate symmetry, particularly in breasts with severe ptosis. With a well-trained surgical team, the procedure can be conducted on both sides at the same time, consequently reducing the operative time. When performing symmetrization, the surgeon can use this opportunity to ressect any suspicious breast lesion that may have been revealed by a preoperative exams (15,35).

Type IIC

Defects are analyzed individually according to the size of the breast defect in relation to the remaining breast tissue available. For this purpose, the patient is positioned upright to assess the amount of the remaining glandular tissue. Thus, the type IIC can be subclassified into favorable and unfavorable defects. If there is enough tissue to perform an adequate breast mound shaping the defect is classified as favorable. For the lateral defects, the extended LTDF is most commonly employed where the inferior and superior limits are designed more obliquely with curved borders to incorporate a large amount of subcutaneous tissue from the lateral and posterior region of the thorax. In patients with central and medial defects, the extended LDMF can be utilized (13). Conversly, if not enough breast tissue remains, the breast defect is classified as unfavorable and a SSM and total reconstruction is indicated.

Type IIIB

Defects are frequently reconstructed with BRM techniques when the patient presents large volume breasts and there is a sufficient amount of breast tissue (Figure 2). The most favorable tumor location is in the lower breast pole where a conventional superior pedicle or superior-medial technique can be utilized (15,16). In patients with central tumors, an inferior pedicle is used to carry parenchyma and skin into the central defect (17) (Figure 5).

Type IIIC

Breast defects are analyzed individually. When the defect is favorable the deficiency is most frequently reconstructed with BRM. A marked reshaping of the breast with available tissue and a similar contralateral breast reduction is then performed. In patients in which the relation is not favorable a skin-sparing mastectomy and total breast reconstruction with an appropriate technique can be indicated.

Clinical results of oncoplastic breast surgery

Immediate BCS reconstruction is challenging for oncological and plastic surgeons, demanding understanding of the breast anatomy, ability in reconstructive techniques and a sense of volume, shaping techiques and symmetry. It has been our impression that this approach has evident advantages, and there is no doubt that this concept will become more widely available and possibly become standard practice in the future (3). At the present time, optimal treatment should be correct, adequate and preventive by performing immediate reconstruction, before radiotherapy (9,19,26). However, to date there is limited evidence in the plastic and breast surgery literature on the safety and aesthetic clinical results of the oncoplastic techniques (8-10,19,20,26,31,38). In fact, the great part of these clinical series are retrospective studies, generally based on a limited number of patients and sometimes only a single surgeon’s experience. In addition, there are a small number of data on its impact on local recurrences, distant metastasis and overall survival (9,25). Kronowitz et al. (9) in a review of 69 patients observed local recurrence in 2% of immediate oncoplastic reconstructions and in 16 percent of delayed (P=0.06). The difference observed between the two groups can be explained by the advanced tumor stage for the patients who had a delayed reconstruction. Similarly, Clough et al. (38) with a median follow-up of 46 months reported 101 patients who were underwent BCS and oncoplastic reconstruction. Local recurrence developed in 11 cases (5-year local recurrence rate was 9.4%). Thirteen patients developed metastases and eight died of their disease (5-year metastasis-free survival of 82.8% and an overall survival rate of 95.7%). Recently, Rietgens et al. (20) reported the long-term oncological results of the oncoplastic reconstruction in a series of 148 patients. With a median follow-up of 74 months, 3% developed an ipsilateral breast cancer recurrence 13% developed distant metastasis. According to the authors the rate of local recurrence after 5 years was low in their series when compared with the 14.3% of cumulative incidence in the NSABP trial, the 9.4% after 5 years in the Institut Curie study and the 0.5% after 5 years in the Milan I trial. Consequently, the oncoplastic approach associated with BCS can be considered as safe as mastectomy in tumours less than 2 cm and possibly safer than the BCS.

Concerning the aesthetic results there is limited evidence of the oncoplastic procedures. In addition, the methods of aesthetic evaluation vary significantly (9,10). Some authors reported that the amount of glandular and skin tissue ressection is directly associated to the aesthetic outcome (39-41). Olivotto et al. (39) and Mills et al. (40) have documented that excision of a volume greater than 70 cm3 in medium-size breasts often leads to unsatisfactory aesthetic results. Gendy et al. (28), retrospectively compared the aesthetic outcomes of 106 patients. Although the panel scored the cosmetic outcome quite high, the cosmetic failure rate was 18% on breast retraction assessments. The authors demonstrated an advantage for the BCS reconstruction with regard to the incidence of complications (8% versus 14%), additional surgery (12% versus 79%), and restricted activities (54% versus 73%). Clough et al. (38) in a panel of three assessed cosmetic results at 2 and 5 years. At 2 years 88% and at 5 years 82% of patients had a fair to excellent outcome. A significantly worse aesthetic outcome was observed in the 13 patients that received pre-operative radiotherapy compared to the remainder which were given radiotherapy postoperatively (poor outcome 42.9 vs. 12.7%, P<0.02). Recognizing that there is a small risk for local recurrence and based on clinical series previously published, we believe that immediate aplication of oncoplastic procedures could be a reasonable and safe option for early-breast-cancer patients who desire BCS.

Limitations of oncoplastic breast surgery

Complications rates, adjuvant treatment and surveillance

One of the limitations concerning the BCS reconstruction at the time of oncological surgery is that the additional procedure would result in complications and delay adjuvant therapy. In a recent published meta-analysis, the average complication rate in the oncoplastic reduction mammaplasty group was 16%, and in the oncoplastic flap reconstruction group was 14% (42). However, there was no delay in the initiation of adjuvant therapy. According to the authors, it does not seem that complications in the oncoplastic groups, although potentially higher, have any negative impact on patient care from an oncologic point of view. In fact, adequate technique and patient selection is crucial in order to minimize morbidity when this oncoplastic techniques are selected (42,43).

Concerning late complications, the most common event is related to fat necrosis. In our previous experience comparing immediate and delayed BCS reconstruction with reduction mammplasty techniques, this complication was significantly higher in the delayed group (19). It has been our impression that radiation therapy played a significant role and contributed to development of fat necrosis. One might surmise that in delayed reconstructions, a slower reestablishment of a local blood supply to rearranged breast tissues from the underlying irradiated chest wall can be observed. In addition, previous breast tissue scarring and local effects of radiotherapy can also disrupt the local blood supply and the ability to create a safe parenchymal pedicle (9,19). Thus, in these patients a careful surveillance is prudent since the risk of local recurrence is always possible. According to Losken et al. (26), postoperative surveillance is not impaired by simultaneous BM. In some cases, calcifications and fat necrosis can simulate tumor recurrence; however, these aspects can be distinguished on mammogram or core biopsy (15-17,26).

Opposite breast (OB) surgery

Another important issue is related to the OB surgery. In our previous experiences, all patients submitted to reduction mammaplasty reconstruction had bilateral procedures (15-17), and almost 40% of patients submitted to volume replacement underwent a contra-lateral breast surgery in order to achieve a satisfactory outcome (13,14). In fact, Kronowitz et al. (44) observed a significant relationship existing between the reconstructive technique and the need for an OB reduction. This aspect can be viewed as a negative point, however it also has the advantages of allowing for sampling of glandular tissue (15-17,19,21,35,44). In our previous study (19), we report our experience with surgical management and outcome in BCS reconstruction with BM techniques with regard to whether immediate or delayed reconstruction is better in terms of complication rates. In this series, in three patients (2.8 percent) an unexpected cancer in the OB was observed in immediate reconstruction. Although the diagnosis of occult cancer is not a reason to perform an OB reduction, this procedure can be advantageous for high-risk patients and especially for patients with previous breast cancer (19).

Postoperative radiation and boost therapy planning

All immediate techniques that involve rearrangement of glandular tissue may jeopardize the boost radiation dose delivery since the target area for the radiation is defined as the site of the tumor (15,45). For this reason, a coordinated planning with the multidisciplinary team, especially with the radiotherapy group is crucial since some oncoplastic techniques alter the normal architecture of the breast (15,16). To locate the original tumor area we recommend orienting the tumor site by skin markings and also placing surgical clips at the tumor margins. It has been our impression and similar as observed by a other authors (45-47) that identification of the original tumor bed based only on physical exam, without precise imaging information, can result in missing the primary tumor bed in a substantial percentage of patients. In our previous experience (15-17), surgical clips have not interfered with mammography, and, actually, have helped recognize areas at risk for recurrence. Additionally, clips have not been mentioned as interfering with physical examination or cosmesis or to have added to any morbidity related to the reconstructive procedure (45).

Another important issue is related to delayed reconstruction following radiotherapy. Frequently, the appearance of the radiated breast is less pleasing than the nonradiated one and total dose, the boost therapy and the number of radiation fields may be involved (19,21,23,24). Losken et al. (24), emphasized that when radiation is expected, the possibility of fibrosis/atrophy should be taken into account in an attempt to preserve symmetry. The authors suggested a less aggressive reductions on the ipsilateral breast to accommodate for any additional size distortion. Additionally, some authors advocated that oncoplastic reconstruction with radiation is best achieved using autologous, nonirradiated flaps (6,9,11,19).

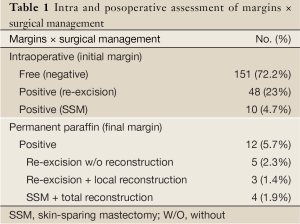

Final surgical margins assessment and immediate reconstruction

Techniques that involve rearrangement of glandular tissue make reexcision difficult in cases where close or positive margins are observed (31). This fact could make it difficult to locate the residual tumor and to perform margin reexcision. In our previous studies (14-17), intraoperative margin evaluation was assessed by pathological monitoring, which is based on radiological, macroscopic, and histological examination of frozen sections. In our previous experience, positive margins discovered on permanent pathology in a previously negative margin patient were observed in 5.5 percent (31) (Table 1). Previous studies have been investigating the risk factors to identify patients with a high probability of having positive margins following CBS (26,31,48-53). In fact, younger age (26,31,52,53), histopathologic characteristics (in situ carcinoma) (26,52-54), and larger tumor size (31,53) have all been associated with positive margins. Our results were comparable to those of the previous studies with young patients and larger tumor size as more likely to have positive margins (31). Our data suggest that patients with those characteristics require more meticulous intraoperative margins evaluation to avoid the need for re-operation. Concerning the reoperative rates, Olson et al. (49) observed that 11.3% of patients submitted to CBS require second operations to achieve negative margins. Weinberg et al. (55) observed that 6.2% had later re-excisions and Cendán et al. (56), reported that 19.6% of subjects required additional operations to clear surgical margins. In spite of these aspects, the positive margins can be effectively managed with either re-excision with/without reconstruction or with skin-sparing mastectomy and total reconstruction, depending on the extention of tissue ressection, preference, and pathology. The decision to re-operate depends on the extent of tumor involvement, whether the dissection had already been extended to the chest wall or skin, or whether the patient had opted to proceed with a total reconstruction. It has been our impression that re-operation was not a disadvantage in these patients and the negative aspect of a more extensive surgery is negligible. However, it is important that the patient should be appropriately informed about the risk of further positive margins and the requirement of an additional surgery (31). Thus, intraoperative assessment of surgical margins require multidisciplinary cooperation among oncological and plastic surgeons and pathologists. Diverse techniques have been described, depending on the tumor type, size, the CBS technique, and whether or not the tumor is palpable (31,49,54). Unfortunately, all techniques can present some limitations and as with any other test, there is an inherent false-negative rate (31). According to Losken et al. (26), all patients should be informed preoperatively on the potential need for a delayed-immediate approach. Additionally, these high-risk patients can be better managed by staged procedures and confirmation of negative margins prior to CBS reconstruction (26,31).

Full Table

Delayed BCS reconstruction and outcome

Another important issue is related to the complication rates and the timing of reconstruction. In our previous series, delayed reconstruction complication rates have been shown to be higher than immediate reconstruction (31 versus 22 percent respectively) (19). However, this aspect was not significant (P=0.275). Thus, our results indicate that timing of reconstruction is not a significant predictor of complications following BCS reconstruction with BM. This finding is contradictory to published reports that suggest that delayed BCS reconstruction has a significantly higher complication rate compared with immediate procedures (9,38). In fact, Kronowitz et al. (9) observed that delayed reconstruction was associated with a complication rate almost twice that of immediate. In our study, the relatively small number of patients and especially the small number of obese patients in the delayed group (21.7 versus 10.5 percent) may have influenced this comparison. Thus, a large number of patients and a prospective and controlled sample are necessary for definitive conclusions.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1227-32. [PubMed]

- Hamdi M, Wolfli J, Van Landuyt K. Partial mastectomy reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg 2007;34:51-62. [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Aldrighi CM, Ferreira MC. Paradigms in oncoplastic breast surgery: a careful assessment of the oncological need and aesthetic objective. Breast J 2007;13:326-7. [PubMed]

- Audretsch WP, Rezai M, Kolotas C, et al. Tumor-specific immediate reconstruction in breast cancer patients. Persp Plast Surg 1998;11:71-100.

- Huemer GM, Schrenk P, Moser F, et al. Oncoplastic techniques allow breast-conserving treatment in centrally located breast cancers. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;120:390-8. [PubMed]

- Slavin SA, Halperin T. Reconstruction of the breast conservation deformity. Semin Plast Surg 2004;18:89-96. [PubMed]

- Clough KB, Kroll SS, Audretsch W. An approach to the repair of partial mastectomy defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;104:409-20. [PubMed]

- Clough KB, Thomas SS, Fitoussi AD, et al. Reconstruction after conservative treatment for breast cancer: cosmetic sequelae classification revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;114:1743-53. [PubMed]

- Kronowitz SJ, Feledy JA, Hunt KK, et al. Determining the optimal approach to breast reconstruction after partial mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:1-11. [PubMed]

- Asgeirsson KS, Rasheed T, McCulley SJ, et al. Oncological and cosmetic outcomes of oncoplastic breast conserving surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 2005;31:817-23. [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Montag E, Arruda E, et al. Assessment of immediate conservative breast surgery reconstruction: a classification system of defects revisited and an algorithm for selecting the appropriate technique. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;121:716-27. [PubMed]

- Papp C, Wechselberger G, Schoeller T. Autologous breast reconstruction after breast-conserving cancer surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102:1932-6. [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Montag E, Fels KW, et al. Outcome analysis of breast-conservation surgery and immediate latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction in patients with T1 to T2 breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;116:741-52. [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Montag E, Arruda EG, et al. The role of the lateral thoracodorsal fasciocutaneous flap in immediate conservative breast surgery reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:1699-710. [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Montag E, Arruda EG, et al. Critical analysis of reduction mammaplasty techniques in combination with conservative breast surgery for early breast cancer treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:1091-103; discussion 1104-7. [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Montag E, Arruda EG, et al. Superior-medial dermoglandular pedicle reduction mammaplasty for immediate conservative breast surgery reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 2006;57:502-8. [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Montag E, Arruda E, et al. Reliability of inferior dermoglandular pedicle reduction mammaplasty in reconstruction of partial mastectomy defects: surgical planning and outcome. Breast 2007;16:577-89. [PubMed]

- Spear SL, Pelletiere CV, Wolfe AJ, et al. Experience with reduction mammaplasty combined with breast conservation therapy in breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003;111:1102-9. [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Aldrighi CM, Montag E, et al. Outcome analysis of immediate and delayed conservative breast surgery reconstruction with mastopexy and reduction mammaplasty techniques. Ann Plast Surg 2011;67:220-5. [PubMed]

- Rietjens M, Urban CA, Rey PC, et al. Long-term oncological results of breast conservative treatment with oncoplastic surgery. Breast 2007;16:387-95. [PubMed]

- Chang E, Johnson N, Webber B, et al. Bilateral reduction mammoplasty in combination with lumpectomy for treatment of breast cancer in patients. Am J Surg 2004;187:647-50; discussion 650-1. [PubMed]

- Brierley JD, Paterson IC, Lallemand RC, et al. The influence of breast size on late radiation reaction following excision and radiotherapy for early breast cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1991;3:6-9. [PubMed]

- Gray JR, McCormick B, Cox L, et al. Primary breast irradiation in large-breasted or heavy women: analysis of cosmetic outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991;21:347-54. [PubMed]

- Losken A, Elwood ET, Styblo TM, et al. The role of reduction mammaplasty in reconstructing partial mastectomy defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;109:968-75; discussion 976-7. [PubMed]

- Kaur N, Petit JY, Rietjens M, et al. Comparative study of surgical margins in oncoplastic surgery and quadrantectomy in breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12:539-45. [PubMed]

- Losken A, Styblo TM, Carlson GW, et al. Management algorithm and outcome evaluation of partial mastectomy defects using reduction or mastopexy techniques. Ann Plast Surg 2007;59:235-42. [PubMed]

- Fitzal F, Mittlboeck M, Trischler H. Breast-conserving therapy for centrally located breast cancer. Ann Surg 2008;247:470-6. [PubMed]

- Kronowitz SJ, Feledy JA, Hunt KK, et al. Determining the optimal approach to breast reconstruction after partial mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:1-11; discussion 12-4. [PubMed]

- Berrino P, Campora E, Santi P. Postquadrantectomy breast deformities; classification and techniques of surgical correction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1987;79:567-72. [PubMed]

- Clough KB, Kroll SS, Audretsch W. An approach to the repair of partial mastectomy defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;104:409-20. [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Montag E, Arruda E, et al. Immediate reconstruction following breast-conserving surgery: Management of the positive surgical margins and influence on secondary reconstruction. Breast 2009;18:47-54. [PubMed]

- Holmström H, Lossing C. The lateral thoracodorsal flap in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1986;77:933-43. [PubMed]

- Kroll SS, Singletary SE. Repair of partial mastectomy defects. Clin Plast Surg 1998;25:303-10. [PubMed]

- Gendy RK, Able JA, Rainsbury RM. Impact of skin-sparing mastectomy with immediate reconstruction and breastsparing reconstruction with miniflaps on the outcomes of oncoplastic breast surgery. Br J Surg 2003;90:433-9. [PubMed]

- Ricci MD, Munhoz AM, Pinotti M, et al. The influence of reduction mammaplasty techniques in synchronous breast cancer diagnosis and metachronous breast cancer prevention. Ann Plast Surg 2006;57:125-32; discussion 133. [PubMed]

- Ribeiro L. A new technique for reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1975;55:330-4. [PubMed]

- Courtiss EH, Goldwyn RM. Reduction mammaplasty by the inferior pedicle technique. Plast Reconstr Surg 1977;59:500-7. [PubMed]

- Clough KB, Lewis JS, Couturaud B, et al. Oncoplastic techniques allow extensive resection for breast-conserving therapy of breast carcinomas. Ann Surg 2003;237:26-34. [PubMed]

- Olivotto IA, Rose MA, Osteen RT, et al. Late cosmetic outcome after conservative surgery and radiotherapy: analysis of causes of cosmetic failure. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1989;17:747-53. [PubMed]

- Mills JM, Schultz DJ, Solin LJ. Preservation of cosmesis with low complication risk after conservative surgery and radiotherapy for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997;39:637-41. [PubMed]

- Cochrane RA, Valasiadou P, Wilson AR, et al. Cosmesis and satisfaction after breast-conserving surgery correlates with the percentage of breast volume excised. Br J Surg 2003;90:1505-9. [PubMed]

- Losken A, Dugal CS, Styblo TM, et al. A meta-analysis comparing breast conservation therapy alone to the oncoplastic technique. Ann Plast Surg 2013. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Fitoussi AD, Berry MG, Famà F, et al. Oncoplastic breast surgery for cancer: analysis of 540 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;125:454-62. [PubMed]

- Kronowitz SJ, Hunt KK, Kuerer HM, et al. Practical guidelines for repair of partial mastectomy defects using the breast reduction technique in patients undergoing breast conservation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;120:1755-68. [PubMed]

- Solin LJ, Danoff BF, Schwartz GF, et al. A practical technique for the localization of the tumor volume in definitive irradiation of the breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1985;11:1215-20. [PubMed]

- Solin LJ, Chu JC, Larsen R, et al. Determination of depth for electron breast boosts. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1987;13:1915-9. [PubMed]

- Regine WF, Ayyangar KM, Komarnicky LT, et al. Computer-CT planning of the electron boost in definitive breast irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991;20:121-5. [PubMed]

- Laucirica R. Intraoperative assessment of the breast: guidelines and potential pitfalls. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2005;129:1565-74. [PubMed]

- Olson TP, Harter J, Muñoz A, et al. Frozen section analysis for intraoperative margin assessment during breast-conserving surgery results in low rates of re-excision and local recurrence. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:2953-60. [PubMed]

- Balch GC, Mithani SK, Simpson JF, et al. Accuracy of intraoperative examination of surgical margin status in women undergoing partial mastectomy for breast malignancy. Am Surg 2005;71:22-7; discussion 27-8. [PubMed]

- Singletary SE. Surgical margins in patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast conservation therapy. Am J Surg 2002;184:383-93. [PubMed]

- Obedian E, Haffty BG. Negative margin status improves local control in conservatively managed breast cancer patients. Cancer J Sci Am 2000;6:28-33. [PubMed]

- Tartter PI, Kaplan J, Bleiweiss I, et al. Lumpectomy margins, re-excision, and local recurrence of breast cancer. Am J Surg 2000;179:81-5. [PubMed]

- Cabioglu N, Hunt KK, Sahin AA, et al. Role for intraoperative margin assessment in patients undergoing breast-conserving surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:1458-71. [PubMed]

- Weinberg E, Cox C, Dupont E, et al. Local recurrence in lumpectomy patients after imprint cytology margin evaluation. Am J Surg 2004;188:349-54. [PubMed]

- Cendán JC, Coco D, Copeland EM 3rd. Accuracy of intraoperative frozen-section analysis of breast cancer lumpectomy margins. J Am Coll Surg 2005;201:194-8. [PubMed]