Patient related outcome measures for breast augmentation mammoplasty: a systematic review

Introduction

Breast augmentation is the most common aesthetic operation worldwide (1). With the increasing incidence of women undergoing this procedure, breast implant registries have been established in several countries, including Australia, Sweden and Holland. These registries function to provide real world data regarding patient demographics, implant information and outcomes relating to breast device performance and epidemiological data regarding implant-associated pathologies (2).

Traditionally, outcome measures for bilateral augmentation mammoplasty (BAM) were surgeon-based success related to short and long-term outcomes (1,3-6). However recent trends are focused on patient-reported outcome measures (PROM), which may differ significantly from a surgeon’s perspective (7). These measures focus on activities of daily living, sexual wellbeing, physical wellbeing; variables not previously measured by surgeons (8).

With routine use of PROM for BAM being in its infancy, we investigate what PROM relevant to BAM exist, and which are the most robust.

Methods

A Medline search for publications between 1966 and 2018, using the search strategy (“patient reported outcome measure” OR “surveys or questionnaires”) AND “breast” AND (“augment” OR “implant”) was performed. A manual search with Google Scholar using the search term “Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Bilateral Augmentation Mammaplasty” was also performed. Once the search yielded its results, a further search of bibliographic references within the articles was also performed.

Duplicate publications were removed and the search was limited to English language articles only. A single author (DW) read each article to assess eligibility and relevance for PROM, population and outcomes of interest. The predetermined inclusion criteria for this systematic review were English language only articles addressing female aesthetic breast augmentation patients, older than 18 years of age, that had utilized a PROM with a validated tool.

Results

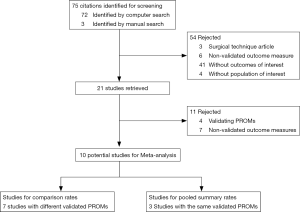

The Medline computer search produced 72 results, with a Google Scholar search yielding two results and a bibliographic search of all articles revealing a further single result.

Fifty-four articles were excluded because they used a non-validated PROM, were a description of a surgical technique or analyzed an outcome or population that was not part of the inclusion criteria. Of these 54 publications, three articles were rejected as they described surgical techniques for BAM only. Six articles used unvalidated PROMs. Forty-one articles looked at BAM but did not describe outcomes of interest, such as comparing PROM with different types of implants (9), or defined cup size (10), or explore patient’s goals (7) or described re-operation rates on different approaches to BAM (11). Four papers had a population that was not of interest such as transgender (12), augmentation-mastopexy (13,14) and comparison of BAM to other day procedures (15).

Study attrition diagram can be seen below (Figure 1).

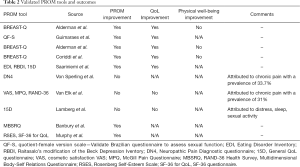

Ten studies were included as they used validated PROM. Three articles used the same PROM (Breast-Q) and seven used different PROM (Table 1).

Full table

Pooled group

Alderman et al. (1), Alderman et al. (16) and Coriddi et al. (8) constitute the pooled group. They all used the same PROM tool, BREAST-Q. Patient populations had the same mean BMI of 22, and ages were 34–36. Mean follow-up was varied from 6 weeks to 4 years. Number of patients also varied significantly from 155 to 14,514 (1,8,16).

All results from validated PROM studies had the same conclusion: there was a significant (P<0.001) improvement in sexual and psychosocial well-being and satisfaction with breasts post BAM. There was a significant (P<0.05) decrease in physical wellbeing post BAM (Table 2).

Full table

Comparison group

The remaining studies constituted the comparison group. Each study used a different PROM [Quotient-Female version scale (QF-S) (17), Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI) (18), Raitasalo’s modification of the Beck Depression Inventory (RBDI) (18), 15D general QoL questionnaire (18), Neuropathic Pain Diagnostic (DN4) questionnaire (19), Cosmetic satisfaction VAS (20), McGill Pain Questionnaire (20), RAND-36 Health Survey (20), Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (21), Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, SF-36 for QoL (22)]. Mean ages were 26–35 years with BMI averages from 21–22. The comparison group had a follow-up time of 6–112 months, with 46–494 patients for follow-up.

Guimarães (17) QS-F found significant increased (P<0.05) in foreplay, excitement and orgasm post BAM. Saariniemi (18) demonstrated (P<0.05) decreased depression and increased self-esteem post BAM. von Sperling (19) revealed 33.7% had chronic pain post BAM and this adversely affected their satisfaction with their result. van Elk (20) also found chronic pain in 31% significantly decreased QoL in BAM patients (P<0.001). Lamberg (23) found age-matched non BAM patient controls had similar QoL measures, except for distress, sexual activity and sleep. Banbury (21) utilized MBSR to show statistically significant (P<0.05) improvement pre and post BAM appearance and body-area satisfaction.

Three studies [von Sperling et al. (19), van Elk et al. (20), Lamberg et al. (23)] demonstrated no improvement in PROM post BAM. Two of the studies attributed this to chronic pain post-operatively, whereas Lamberg et al. found decreased PROM due to disturbance of sleep and sexual activity and increased distress (Table 2).

Discussion

Traditional outcome measures for BAM have been historically surgeon based and PROMs have been largely unvalidated and reported varied outcomes. However, a number of PROMs have been developed, and have been able to provide insight into outcomes of BAM.

Patient QoL following BAM as measured by the BREAST-Q has a statistically significant improvement in terms of satisfaction with breasts, psychosocial and sexual wellbeing. This finding has been supported by studies employing other measurement tools, including Saariniemi (18), Banbury (21) and Murphy (22). Overall, the majority (70%) of the included studies demonstrated a benefit in PROM.

However, the domain of physical wellbeing was found to decrease post-operatively, thought to be secondary to pain. This may be due to early post-operative pain, as Alderman et al. (24) demonstrated physical well-being to decrease at the 6-week post-operative mark and then improve somewhat at 6 months. This phenomenon is also supported by von Sperling et al. (19), van Elk et al. (20) and Lamberg et al. (23), which used different PROM, each concluding decreased PROM due to chronic pain, distress, sleep or sexual activity. van Elk (20) and von Sperling (19) found an incidence of 31% and 33%, respectively. This high incidence of chronic pain may detract partially from the benefits on psychosocial and sexual wellbeing, QoL and satisfaction with breasts in the initial 6 months post-BAM.

Physical well-being as analyzed by BREAST-Q has only been follow-up for 6 months post-operatively (22). This is a limitation to its interpretation. Studies focusing on post-operative pain are also limited by their retrospective nature, but have a longer follow-up of 27 and 31 months (19,20).

Of the validated PROM tools, BREAST-Q is the most used and best validated, investigating four major domains of QoL, including satisfaction with breasts, psychosocial well-being, sexual well-being and physical well-being. It further investigates patient satisfaction with the information provided by their surgeon, as well as members of the surgical and administrative teams. The other PROM tools are used for one dimensional outcomes, which are useful for specifically assessing sexual well-being, pain, cosmetic satisfaction, or depression and self-esteem.

To continue providing objective measures of BAM outcomes, surgeon-based outcome measures and PROM should be incorporated into practice. This will ensure that both surgeon and patient expectations can be objectively assessed. PROM further offers a means to gauge improvement in patient and surgeon-based outcomes both in the short- and long-term. Combined with the implant registry, there is an additional layer to match these outcomes with patient demographics, particular procedures and specific types of implants.

Conclusions

Bilateral augmentation mammoplasty has been demonstrated to confer an increase in patient reported outcomes in domains of satisfaction with breasts and psychological well-being. There is some decrease in physical well-being following this procedure. Validated PROMs provide objective data relating to different aspects of BAM. Combined with traditional surgeon-based outcome measures and implant registry data, they may provide a more comprehensive insight into the patient journey.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Available online: (accessed on 3/3/19)https://www.isaps.org/wp.content/uploads/2018/10/ISAPS_2017_International_Study_Cosmetic_Procedures.pdf

- Hopper I, Ahern S, Nguyen TQ, et al. Breast Implant Registries: A call to action. Aesthet Surg J 2018;38:807-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Broer PN, Juran S, Walker ME, et al. Aesthetic breast shape preferences among plastic surgeons. Ann Plast Surg 2015;74:639-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hölmich LR, Breiting VB, Fryzek JP, et al. Long-term cosmetic outcome after breast implantation. Ann Plast Surg 2007;59:597-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Fells K, Arruda E, et al. Subfascial transaxillary breast augmentation without endoscopic assistance: technical aspects and outcome. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2006;30:503-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spear SL, Pelletiere CV, Menon N. One-stage augmentation combined with mastopexy: aesthetic results and patient satisfaction. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2004;28:259-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paraskeva N, Clarke A, Grover R, et al. Facilitating shared decision-making with breast augmentation patients: Acceptability of the PEGASUS intervention. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2017;70:203-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coriddi M, Angelos T, Nadeau M, et al. Analysis of satisfaction and well-being in the short follow-up from breast augmentation using the BREAST-Q, a validated survey instrument. Aesthet Surg J 2013;33:245-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gryskiewicz J, LeDuc R. Transaxillary Nonendoscopic Subpectoral Augmentation Mammaplasty: A 10-Year Experience With Gel vs Saline in 2000 Patients-With Long-Term Patient Satisfaction Measured by the BREAST-Q. Aesthet Surg J 2014;34:696-713. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- King NM, Lovric V, Parr WCH, et al. What Is the Standard Volume to Increase a Cup Size for Breast Augmentation Surgery? A Novel Three-Dimensional Computed Tomographic Approach. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;139:1084-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Benito-Ruiz J, Manzano ML, Salvador-Miranda L. Five-Year Outcomes of Breast Augmentation with Form-Stable Implants: Periareolar vs Transaxillary. Aesthet Surg J 2017;37:46-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weigert R, Frison E, Sessiecq Q, et al. Patient satisfaction with breasts and psychosocial, sexual, and physical well-being after breast augmentation in male-to-female transsexuals. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;132:1421-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown T. Patient expectations after breast augmentation: the imperative to audit your sizing system. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2013;37:1134-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fryzek JP, Signorello LB, Hakelius L, et al. Self-reported symptoms among women after cosmetic breast implant and breast reduction surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;107:206-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brattwall M, Stomberg MW, Rawal N, et al. Patient assessed health profile: a six-month quality of life questionnaire survey after day surgery. Scand J Public Health 2010;38:574-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alderman AK, Bauer J, Fardo D, et al. Understanding the effect of breast augmentation on quality of life: prospective analysis using the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;133:787-95. [PubMed]

- Guimarães PA, Resende VC, Sabino Neto M, et al. Sexuality in Aesthetic Breast Surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2015;39:993-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saariniemi KM, Helle MH, Salmi AM, et al. The effects of aesthetic breast augmentation on quality of life, psychological distress, and eating disorder symptoms: a prospective study. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2012;36:1090-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Sperling ML, Hoimyr H, Finnerup K, et al. Persistent pain and sensory changes following cosmetic breast augmentation. Eur J Pain 2011;15:328-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Elk N, Steegers MA, van der Weij LP, et al. Chronic pain in women after breast augmentation: prevalence, predictive factors and quality of life. Eur J Pain 2009;13:660-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banbury J, Yetman R, Lucas A, et al. Prospective analysis of the outcome of subpectoral breast augmentation: sensory changes, muscle function, and body image. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;113:701-7; discussion 708-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murphy DK, Beckstand M, Sarwer DB. A prospective, multi-center study of psychosocial outcomes after augmentation with natrelle silicone-filled breast implants. Ann Plast Surg 2009;62:118-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lamberg S, Manninen M, Kulmala I, et al. Health-related quality of life issues after cosmetic breast implant surgery in Finland. Ann Plast Surg 2008;61:485-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alderman AK, Bauer J, Fardo D, et al. Understanding the effect of breast augmentation on quality of life: prospective analysis using the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;133:787-95. [PubMed]