Minimalist breast conserving surgical approaches for inferiorly sited cancers

Introduction

Contemporary data suggests that breast conservation treatment (BCT) may confer survival advantage compared to mastectomy (1,2). However, it is known that poor cosmetic outcomes with BCT are common pitfalls (3). In an effort to avoid poor cosmetic outcomes, oncoplastic breast surgery (OBS) techniques have been developed (4-6). These are classified into two broad categories: volume replacement and volume displacement techniques (6). Volume displacement, or tissue rearrangement, procedures do not involve the use of implants or autologous flaps, and are considered to be the preferred modality, as volume replacement is reportedly associated with higher complication rates (6). Still, many of these require mammoplasty-like manoeuvres with the creation of extensive local tissue flaps and contralateral reduction mammoplasty (4-6). A high level of surgical training and resource allocation are needed for these. Furthermore, there is data to support intuitive observation that such mammoplasty or mastopexy techniques require longer operating times and result in lower patient satisfaction with scar appearance than standard breast conservation surgery (7). OBS, which is advocated for its ability to offer larger margins without compromising aesthetics, has not been conclusively shown to improve local control (8). Data also indicates that mammoplasty and symmetrisation procedures are associated with higher complication rates than standard lumpectomy with full thickness parenchymal closure (4,6,7,9,10). The significant displacement of parenchymal pillars which formed the original cavity wall with mammoplasty techniques has raised concern as identification of involved margins and delivery of radiotherapy boosts may be impaired (11,12). These collective difficulties may be reduced by adopting the use of less extensive surgery, “reductionist” or “minimalist” approaches. Its essence lies in applying standard breast conserving surgery with direct parenchymal closure in its most uncomplicated form. The increased use of minimalist breast conserving surgery (mBCS) does not necessarily conflict with the objective of expanding BCT eligibility or improved cosmetic outcomes if innovative approaches are used when tumours are sited in positions conventionally considered to be relative contraindications to BCT.

Malignancies in the lower hemisphere of the breast pose a particular technical challenge for BCT. Resection of such tumours without due consideration for parenchymal repair often result in several forms of distortion. There may be unsightly depressions, irregular breast contours or “bird-beak” deformities (13). While many surgeons advocate mammoplasty-like techniques to avoid such poor aesthetic outcomes, it is possible to minimise distortion with less complex procedures. Here, several techniques are described which allow good cosmetic outcomes without the need for elaborate surgical procedures. These methods can potentially streamline surgical processes for more efficient treatment in terms of operating time and lower complication rates.

Operative Technique

Principles of surgical approach based on tumour position

There are a few deliberations to be made when planning surgical approach. Consideration is needed for tissues in two different planes, the first consisting of the skin and subcutaneous tissue and the second, breast parenchyma. Although interrelated, due regard should be made on the impact of one on the other. For best results, these two tissue components may occasionally have to be tackled separately during surgery. Incision design involves dissection down to the subcutaneous tissue while resection patterns address complete lesion extirpation from breast parenchyma in full thickness.

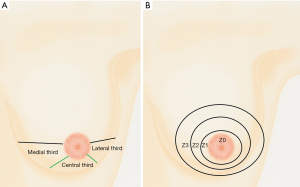

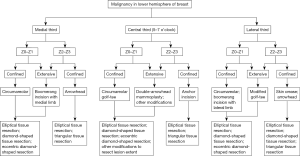

Tumour location is an important factor for determining both incision design and resection pattern. In line with this purpose, the lower hemisphere may be divided into three sections, the medial, central and lateral thirds (Figure 1A). This is considered in conjunction with distance from nipple-areolar complex (NAC), indicated by zones demarcated by three imaginary concentric circles drawn around the areola in proportionately increasing diameter (Figure 1B). Topography of nine sectors is thus provided for surgical planning. Depending on the sector(s) involved, a variety of incisions in conjunction with certain tissue resection patterns may be used to consistently achieve good cosmetic outcomes with standard BCT. These tissue resection patterns follow the patho-anatomy of the “sick lobe” to remove areas affected by genetic predisposition to carcinogenesis (14-16). A suggested algorithm for a standardised surgical approach according to the tumour site and extent of the lesion is provided in Figure 2. Some of these techniques have already been described. However, for clarity, the more commonly employed techniques will be expatiated here in further detail.

Lower medial third

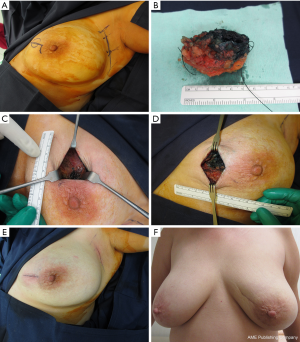

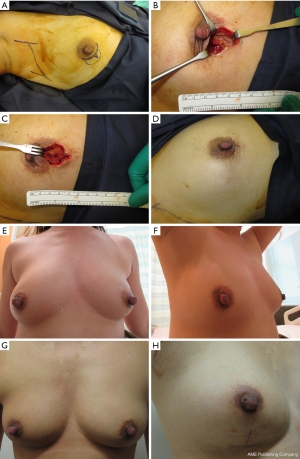

In the past, skin crease incisions were recommended and radial incisions discouraged (17). However, the dual demands of raising the eligibility of BCT with reductionist surgical techniques and achieving optimum cosmetic outcomes in the lower inner quadrant of the breast require different approaches from conventional methods of the past, especially so in terms of skin incisions. For lesions close to the NAC, the boomerang incision or its modifications may be used (18) (Figures 3,4). The boomerang incision is so named as the prototype design, which is a combination of a short section of a crescent around the nipple and a tapered triangular radial limb, resembled a boomerang (18). This incision offers good exposure for lesions close to the nipple. Lesions at the periphery of the breast can be approached using different incisions, the arrowhead (19) or double arrowhead (Figure 5), depending on tumour extent.

Through these incisions, full thickness tumour excision is performed using pre-planned tissue resection patterns. To optimise parenchymal closure and aesthetic results, resection patterns for medial third lesions are usually in similar axis to the incision, although there may be occasions when it is required to different. Elliptical parenchymal tissue resection pattern with the long axis aligned radially approximates closely to the affected “sick lobe” (Figure 3). A modified trapezoid resection pattern may be necessary to accommodate excision of a more extensive lesion. Full thickness parenchymal flaps are mobilised off the pectoralis major muscle, advanced and apposed using absorbable sutures. Skin flaps may need to be raised to avoid skin dune formation along the periphery of the incision. For best results, a skin crease incision in the lower medial third of the breast should be avoided.

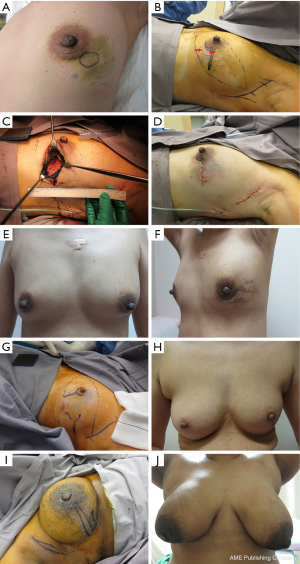

Middle lower third (5–7 o’clock position)

Lesions in close proximity to the NAC in the lower central third of the breast may be approached through a golf-tee incision (20) (Figure 6A-F). This incision is a combination of two boomerang incisions symmetrically placed on either side of an imaginary radial axis, forming a shape resembling a golf-tee. When the tumour is in close proximity to the NAC, a diamond-shaped parenchymal resection pattern may be used. Following resection in this configuration, restoration of cosmesis is optimised after mobilisation of full-thickness tissue flaps with closure in two planes, in a sagittal plane as well as transversely. Lesions at the periphery can be approached through an anchor incision (21) (Figure 6G,H), and excised using either an elliptical or triangular tissue resection pattern. As always, the parenchymal pillars immediately adjacent to the tumour cavity are mobilised and apposed with sutures. This approach allows a good cosmetic result without the need for routine upward nipple displacement. As the parenchymal pillars surrounding the biopsy cavity are apposed beneath the incision, radiotherapy boost may be administered based on scar location. This obviates the need for multiple clips within the breast.

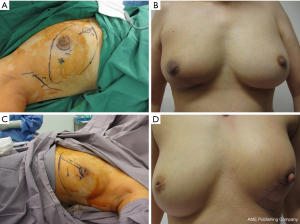

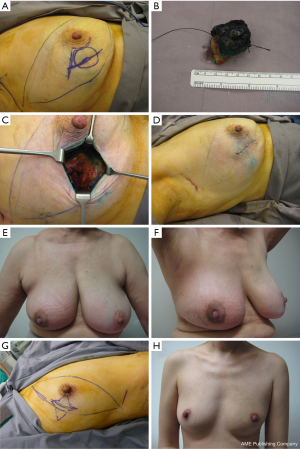

Lower lateral third/lower outer quadrant (LOQ)

Several incision patterns may be used for lesions in the LOQ. For lesions close to the NAC, a boomerang incision consisting of an inferior crescent and a lateral limb is preferred by the author (Figure 7A,B). The length of the lateral limb may be adjusted according to the extent of the disease. Tumour is usually excised through an elliptical resection pattern (Figure 7C). Full thickness parenchymal closure is then performed, followed by skin closure (Figure 7D), which results in acceptable cosmesis (Figure 7E,F). Depending on position and extent of lesion(s), a modified golf-tee incision may also be used (Figure 7G,H). Larger tumours involving a segment extending to the periphery of the breast close to the inframammary fold may be approached through an arrowhead incision (Figure 7I,J).

Skin crease incisions may be used for tumours sited midway between the nipple and the inframammary fold in the LOQ, both for women with smaller breasts with minimal ptosis and those with larger ptotic breasts (Figure 8). In such cases, optimum results are obtained with diamond-shaped tissue resection patterns instead of elliptical excisions. The mobilised parenchymal flaps are apposed both in the radial and circumferential (anti-radial) planes.

For very large lesions in the LOQ, there may be rare occasions when mammoplasty procedures are required if more than 25% of tissue volume is expected to be removed.

Comments

Techniques which raise eligibility for breast conservation are particularly relevant in the current context of potential improved survival and local control with BCT when compared to mastectomy (1,2). A minimalist approach offers shorter operating times, lower complication rates without compromising local control or survival outcomes (4,6-10). Interestingly, data suggests that patients view cosmetic outcomes differently from specialists and computer software programmes, and may rate standard BCT results more favourably than those achieved through mammoplasty (7,22,23). Serious cosmetic deformity can result from OBS (24), while mild distortion and minor asymmetry, as potentially seen with mBCS, may be acceptable to the patient without any impact on quality of life (23). Hence, routinely preforming OBS procedures like reduction mammoplasty for T1 lesions 2–13 mm in size (25,26) may be considered overtreatment.

The use of Level II OBS operations may be further reduced with adoption of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for downstaging (27) and current standards of “no ink on tumour” for margin width (28). Intraoperative assessment with frozen section analysis (29) can offer similar or lower re-excision rates than those reported with mammoplasty (25). Using a combination of available medical technology, resection volume may be reduced to its minimum to achieve negative margins, ensuring adequacy of retained tissue parenchyma for tissue repair in its most uncomplicated form. Neither cosmesis nor local control is significantly compromised, offering possibilities for high conservation rates in populations previously considered to be poor candidates for BCT (30).

The modern era of breast cancer therapy focuses on appropriate therapeutic de-escalation to minimise adverse iatrogenic impact of treatment (31). “Minimalist” or “reductionist” procedures comprising irreducible surgical elements without compromising stringent oncologic principles of negative margins and good cosmetic outcomes would be consistent with this philosophy. In contrast, the routine use of mammoplasty with contralateral symmetrisation, as proposed by some (32), would be antithetic to this concept. This diversity can serve as an impetus for future research to clarify selection criteria for the appropriate use of mBCS, OBS and mastectomy to individualise surgical treatment for optimum outcomes.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

References

- Agarwal S, Pappas L, Neumayer L, et al. Effect of breast conservation therapy versus mastectomy on disease-specific survival for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg 2014;149:267-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Hezewijk M, Bastiaannet E, Putter H, et al. Effect of local therapy on locoregional recurrence in postmenopausal women with breast cancer in the tamoxifen exemestane adjuvant multinational (TEAM) trial. Radiother Oncol 2013;108:190-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baildam AD. Oncoplastic surgery of the breast. Br J Surg 2002;89:532-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clough KB, Kaufman GJ, Nos C, et al. Improving breast cancer surgery: a classification and quadrant per quadrant atlas for oncoplastic surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1375-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Munhoz AM, Montag E, Arruda E, et al. Reliability of inferior dermoglandular pedicle reduction mammoplasty in reconstruction of partial mastectomy defects: surgical planning and outcome. Breast 2007;16:577-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kronowitz SJ, Kuerer HM, Buchholz TA, et al. A management algorithm and practical oncoplastic surgical techniques for repairing partial mastectomy defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;122:1631-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eichler C, Kolsch M, Sauerwald A, et al. Lumpectomy versus mastopexy – a post-surgery patient survey. Anticancer Res 2013;33:731-6. [PubMed]

- De Lorenzi F, Hubner G, Rotmensz N, et al. Oncological results of oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery: long term follow-up of a large series at a single institution: a matched-cohort analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016;42:71-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piper M, Peled AW, Sbitany H. Oncoplastic breast surgery: current strategies. Gland Surg 2015;4:154-63. [PubMed]

- Chatterjee A, Pyfer B, Czerniecki B, et al. Early postoperative outcomes in lumpectomy versus simple mastectomy. J Surg Res 2015;198:143-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eaton BR, Losken A, Okwan-Duodu D, et al. Local recurrence patterns in breast cancer patients treated with oncoplastic reduction mammoplasty and radiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:93-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pezner RD. The oncoplastic breast surgery challenge to the local radiation boost. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;79:963-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holmes DR, Silverstein MJ. Triangle resection with crescent mastopexy: an oncoplastic breast surgical technique for managing inferior pole lesions. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:3289-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tot T. The theory of the sick lobe and the possible consequences. Int J Surg Pathol 2007;15:369-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tot T. Subgross morphology, the sick lobe hypothesis, and the success of breast conservation. Int J Breast Cancer 2011;2011:634021. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dooley W, Bong J, Parker J. Redefining lumpectomy using a modification of the “sick lobe” hypothesis and ductal anatomy. Int J Breast Cancer 2011;2011:726384. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American College of Radiology. Practice guideline for breast conservation therapy in the management of invasive breast carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 2007;205:362-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan MP. The boomerang incision for periareolar breast malignancies. Am J Surg 2007;194:690-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan MP. Arrowhead approach for malignancies in the lower hemisphere of the breast. Gland Surg 2016;5:83-5. [PubMed]

- Tan M. The ‘golf-tee’ incision for lower mid-pole peri-areolar cancers. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:438-9. [PubMed]

- Tan MP. How I do it: the anchor incision for low central breast tumours. ANZ J Surg 2012;82:375-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim MK, Kim T, Moon HG, et al. Effect of cosmetic outcome on quality of life after breast cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015;41:426-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santos G, Urban C, Edelweiss MI, et al. Long-term comparison of aesthetical outcomes after oncoplastic surgery and lumpectomy in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:2500-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Acea Nebril B, Cereijo Garea C, García Novoa A. Cosmetic sequelae after oncoplastic surgery of the breast. Classification and factors for prevention. Cir Esp 2015;93:75-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clough KB, Gouveia PF, Benyahi D, et al. Positive margins after oncoplastic surgery for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:4247-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silverstein MJ, Mai T, Savalia N, et al. Oncoplastic breast conservation surgery: The new paradigm. J Surg Oncol 2014;110:82-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Untch M, Konecny GE, Paepke S, et al. Current and future role of neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Breast 2014;23:526-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moran MS, Schnitt SJ, Giuliano AE, et al. Society of Surgical Oncology-American Soceity for Radiation Oncology consensus guideline on margins for breast-conserving surgery with whole-breast irradiation in stages I and II invasive breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:704-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan MP, Sitoh NY, Sim AS. The value of intraoperative frozen section analysis for margin status in breast conservation surgery in a nontertiary institution. Int J Breast Cancer 2014;2014:715404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan MP, Sitoh NY, Sim AS. Breast conservation treatment for multifocal and multicentric breast cancers in women with small-volume breast tissue. ANZ J Surg 2017;87:E5-E10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marescaux J, Diana M. Inventing the future of surgery. World J Surg 2015;39:615-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silverstein MJ. Radical mastectomy to radical conservation (extreme oncoplasty): a revolutionary change. J Am Coll Surg 2016;222:1-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]