Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with intrathyroidal thymic carcinoma (ITC): a retrospective cohort study

Highlight box

Key findings

• Despite with an overall favorable survival, intrathyroidal thymic carcinoma (ITC) is still prone to lymph node and distant metastasis.

What is known and what is new?

• Lateral neck metastasis and incomplete tumor resection predicted a poorer outcome.

• Radical surgery combined with radiotherapy should be performed to improve local control.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Immunotherapy and targeted therapies are potentially effective in advanced disease.

Introduction

First reported in 1985, intrathyroidal thymic carcinoma (ITC), once known as thyroid carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE), is an extremely rare malignancy with a incidence of <0.01% of all thyroid cancers (1). In 2004, it was officially categorized as a separate thyroid tumor type by the World Health Organization (WHO) (2). In the 5th edition of the WHO classification of Endocrine tumors in 2022, this tumor was officially named ITC. The biological behavior of ITC varies in clinical practice. Although ITC sometimes presents with an indolent clinical course, it is also frequently diagnosed at a late stage (3,4).

Molecularly, ITC is characterized by CD5 and CD117 expression, reflecting its thymic epithelial origin, while lacking thyroid-specific markers such as thyroglobulin (Tg) and thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1). These distinct immunoprofiles aid in post-surgical diagnosis but contribute to preoperative diagnostic dilemmas, as fine-needle aspiration (FNA) frequently misclassifies ITC as poorly differentiated carcinoma or metastatic disease (5,6). Preoperative diagnosis of ITC is difficult and is often confused with thyroid squamous cell carcinoma and poorly-differentiated thyroid carcinoma (6). Radical surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy is widely advocated, yet locally advanced cases often require trade-offs between oncological control and functional preservation. For example, tracheal or esophageal invasion may necessitate organ resection with reconstruction, raising debates about quality of life versus survival benefits (7-10).

Despite these challenges, existing ITC literature is limited to small case series due to its extremely low incidence. Consequently, critical questions regarding risk stratification, treatment efficacy, and long-term outcomes remain unresolved. This study analyzes the largest ITC cohort to date (n=43) to address these gaps, with a focus on the clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, therapeutic innovations, and the optimal treatment modality of this disease. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-2025-9/rc).

Methods

Patients

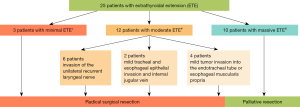

The medical records of all patients with ITC treated at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center from January 2007 to January 2024 were retrospectively reviewed. A total of 55 patients were identified, of whom 12 were excluded according to the following criteria: (I) three patients had very advanced disease without surgical indications, and were only treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy; (II) eight patients received surgery at other hospitals and came to our hospital for adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, details of their clinicopathological information and initial surgery were incomplete; (III) one patient lost contact during follow-up. Finally, 43 cases with ITC were enrolled in this study (Figure 1).

The slides of all patients were reviewed by an experienced pathologist. The typical histologic characteristics of ITC resembled thymoma in our cohort as follows: (I) tumor cells that were spindle, squamoid, or polygonal, with pale cytoplasm and oval, vesicular nuclei having well-defined nucleoli; (II) peritumoral and intratumoral infiltration of many lymphocytes and plasma cells; (III) lobular architecture with fibrous bands separating solid islands of epithelial cells, with well-bordered sheet or solid nest appearances. Different combinations of immunohistochemical (IHC) markers were selected for diagnosis in each case according to their morphological features. The ITC always shows positive for CD5 and CD117, while being negative for TTF-1, thyroglobulin, and PAX8 in the IHC results. Clinical characteristics, preoperative examination, treatment and pathological reports were retrospectively collected. The diagnostic criteria and procedures for distant metastases includes the imaging modalities utilized, for example contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT), CT the standardized review process by two independent radiologists, and the systematic exclusion of synchronous malignancies through clinical history, laboratory tests, and multidisciplinary evaluations.

These patients were followed up for a median of 69 months (range, 12–171 months) until April 1st, 2024. Progression-free survival (PFS) is defined as the duration from treatment to an endpoint, including local progression, local recurrence, distant metastasis or death. Disease-specific survival (DSS) is defined as the duration from treatment to death from ITC.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (No. 050432-2108) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Treatment

Prior to surgery, each patient routinely underwent ultrasonography (US) and enhanced cervical CT examination and US-guided FNA or core needle biopsy (CNB). All patients underwent surgical treatment to remove as much of the tumor as possible with acceptable surgical risk. Radical resection could be operated on the patients with mild extrathyroidal extensions (ETEs) to achieve radical resection without significant risk or injury. Palliative resection is the surgical removal of the tumor as much as possible to reduce the tumor load while ensuring the safety of the patient and the function of vital tissues and organs. Central lymph node dissection is routinely performed for patients with preoperative suspicion of malignancy. Therapeutic lateral or mediastinal neck dissection is conducted for patients with radiologically or cytologically confirmed lateral or mediastinal lymph node metastasis. Intraoperative frozen-section examination is reserved only for incidentally detected suspicious lymph nodes during surgery, where confirming malignancy would directly alter the surgical plan.

Lateral lymph node dissection and mediastinal lymph node dissection were performed only in patients with preoperative suspicion of metastasis of these sites.

Adjuvant radiotherapy was performed for 40 patients (93.0%). All patients received postoperative external radiotherapy by intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) given to the thyroid bed and bilateral cervical lymph node area. The radiation doses ranged from 56 Gy/28 fractions to 66 Gy/33 fractions. The application of chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy has thus far been limited to select cases of advanced-stage disease.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). DSS and PFS was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Multivariate Cox regression analysis is performed to explore the predictive factors of prognosis. Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were used to indicate the risk associated with the risk factors. A two-sided P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

As shown in Table 1, totally 43 cases with ITC were included in our study. The median age at diagnosis was 47 years (range, 29–63 years), and there was no apparent discrepancy between the sex (male: n=20, 46.5%; female: n=23, 53.5%). In our cohort, 29 cases presented with neck swelling, 9 cases with hoarseness, 2 cases with hoarseness and dysphagia, 1 case with dysphagia, 1 case with dysphagia and dyspnea, and 1 case with recurrent cough and shortness of breath. Among the 43 patients, 2 cases underwent CNB preoperatively, both suggesting possible ITC, while the remaining 41 cases underwent FNA. However, only 2 FNA results (4.9%) were suggestive of ITC, 10 cases (24.4%) were diagnosed as poorly differentiated carcinoma, and the remaining 29 cases (70.7%) merely indicated malignancy without specifying the subtype. In our hospital, there were 1–5 operations of ITC per year, while we performed over 5,000 thyroid operations per year.

Table 1

| Characteristics | N=43 | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 23 | 53.5 |

| Male | 20 | 46.5 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–40 | 9 | 20.9 |

| 41–50 | 16 | 37.2 |

| 51–60 | 13 | 30.2 |

| 61–70 | 5 | 11.6 |

| Initial surgery | ||

| Yes | 35 | 81.4 |

| No | 8 | 18.6 |

| Tumor size | ||

| ≤2 cm | 7 | 16.3 |

| >2 cm and ≤4 cm | 22 | 51.2 |

| >4 cm | 14 | 32.6 |

| Extrathyroidal extension | ||

| Yes | 25 | 58.1 |

| No | 18 | 41.9 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||

| No metastasis | 25 | 58.1 |

| Central metastasis | 5 | 11.6 |

| Lateral metastasis | 8 | 18.6 |

| Lateral and mediastinal metastasis | 2 | 4.7 |

| No cervical lymph node dissection | 3 | 7.0 |

| Surgery | ||

| Palliative resection | 10 | 23.3 |

| Radical resection | 33 | 76.7 |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| Yes | 40 | 93.0 |

| No | 3 | 7.0 |

| Prognosis | ||

| No progression | 30 | 69.8 |

| Local recurrence | 2 | 4.7 |

| Distant metastasis | 11 | 25.6 |

| Death | 8 | 18.6 |

ITC, intrathyroidal thymic carcinoma.

Clinicopathological features

All tumors were located in the middle-lower or lower third of the lobe. Regarding tumor size, 83.7% of tumors (n=36) were greater than 2 cm in diameter, including 14 (32.6%) ≥4 cm. ETE was observed in 25 of 43 cases (58.1%, Figure 2). Among these, three patients exhibited mild ETE confined to the strap muscles. Moderate ETE was identified in twelve patients, including six cases with recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement and six cases demonstrating internal jugular vein infiltration or superficial esophageal/tracheal invasion. The remaining ten patients (23.6%) presented with severe ETE characterized by extensive tracheoesophageal extension (n=4) or vascular invasion (common carotid artery: n=4; subclavian artery: n=2), necessitating palliative resection due to unresectable disease progression.

Of the 40 cases receiving neck dissection, 5 patients (12.5%) revealed central neck metastasis, 10 patients (25.0%) had lateral ± mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The other 25 patients (62.5%) were free of nodal spread. Two patients were concurrently diagnosed with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma.

After a careful pathologic review, we confirmed that all cases were positive for CD5 and CD117 in IHC staining, while all cases were negative for Tg and TTF-1. Interestingly, all four patients having IHC testing for programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) showed low expression for these markers [tumor proportion score (TPS): 30%, 40%, 20% and 40%]. Genetic testing was performed in nine patients, seven of whom had no definite driver mutations identified, one with both RET A883V and HRAS G12S mutations (calcitonin was negative in IHC testing of this patient), and one with a CDKN2A A57G mutation.

Outcomes and survival

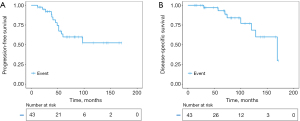

After a median follow-up of 69 months, 30 patients (69.8%) were free of structural recurrence. Two patients revealed recurrence of cervical lymph nodes followed by lung metastases, while 11 patients developed distant metastases, including 9 lung metastases, 1 bone metastasis and 1 liver metastasis. The 3-, 5- and 10-year PFS was 92.1%,59.8% and 52.3%, respectively. Most distant metastases occurred 3 to 5 years after surgery. Eventually, 8 patients died from ITC. The 3-, 5-, and 10-year DSS was 97.0%, 93.1% and 68.4%, respectively (Figure 3).

Risk factors of ITC tumor progression

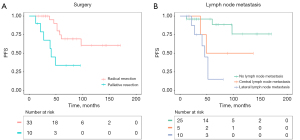

In the univariate Cox regression analysis, we analyzed the factors with PFS and DSS including age, sex, initial surgery or not, radical surgery or not, ETE, tumor size, lymph node dissection or not, T-stage, N-stage, TNM stage, Ki-67 and radiotherapy or not. No significant factor was found to be associated with DSS of the patients with ITC (P>0.05). Palliative resection (HR =3.72, 95% CI: 1.24–11.17, P=0.02), lateral lymph node metastasis (HR =10.02, 95% CI: 2.25–44.71, P=0.003) and Ki-67 labelling index (HR =1.08, 95% CI: 1.00–1.17, P=0.047) were associated with PFS of patients with ITC (Table 2; Figure 4).

Table 2

| Risk factors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Surgery† | 3.72 | 1.24–11.17 | 0.02 | 5.68 | 1.48–21.76 | 0.01 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||||

| No | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Central | 3.72 | 0.62–22.38 | 0.15 | 3.96 | 0.62–25.29 | 0.15 | |

| Lateral | 10.02 | 2.25–44.71 | 0.003 | 12.27 | 2.40–62.81 | 0.003 | |

| Ki-67 | 1.08 | 1.00–1.17 | 0.047 | – | |||

†, surgery: palliative resection/radical resection. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ITC, intrathyroidal thymic carcinoma.

As only 14 patients were tested for Ki-67 labelling index, Ki-67 was not included in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. In the multivariate analysis, palliative resection (HR =5.68, 95% CI: 1.48–21.76, P=0.01) and lateral lymph node metastasis (HR =12.27, 95% CI: 2.40–62.81, P=0.003) were also significantly associated with PFS of patients with ITC (Table 2).

Treatment

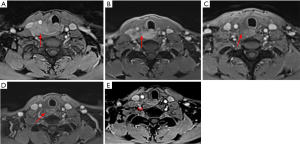

All patients underwent surgical treatment, with radical resection for 33 patients (76.7%), and palliative resection for 10 patients with locally advanced disease (such as invasion of the common carotid artery and subclavian artery). These ten patients with locally advanced disease received palliative resection and postoperative radiotherapy. The postoperative treatment and outcome of these 10 patients were detailed in Table 3. None of them showed progression of the residual tumor, but distant metastasis was observed in 60% of these patients (n=6). The outcome of one patient’s local treatment were shown in Figure 5.

Table 3

| No. | Adjuvant chemotherapy | Regimen | Disease progression | DFS (months) | Salvage therapy | Results | OS (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | DCF*8 | Lung metastases | 41 | No | Death | 74 |

| 2 | Yes | TP*6 | Lung metastases | 39 | Camrelizumab + CEA*6, camrelizumab as the maintenance treatment | PR | 108 |

| 3 | Yes | TP*6 | Lung metastases | 12 | None | Death | 30 |

| 4 | Yes | TP*6 | No | 69 | None | SD | 69 |

| 5 | No | None | Lung metastases | 49 | None | Death | 70 |

| 6 | No | None | Lung metastases | 27 | Lenvatinib | PR | 48 |

| 7 | No | None | Liver metastasis | 21 | TP*6 | PD | 32 |

| 8 | No | None | No | 96 | None | SD | 96 |

| 9 | No | None | No | 69 | None | SD | 69 |

| 10 | No | None | No | 15 | None | SD | 15 |

CEA, cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + etoposide; DCF, docetaxel + cisplatin + fluorouracil; DFS, disease-free survival; TP, paclitaxel + cisplatin; OS, overall survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

Four patients underwent adjuvant chemotherapy, of whom one received 9 courses of DCF regimen (docetaxel + cisplatin + fluorouracil) and three received one course of TP regimen (paclitaxel + cisplatin). The other three patients underwent 6 courses of TP regimen-based chemotherapy after neck recurrence or distant metastasis (shown in Table 3). Three of the four patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy revealed distant metastasis after 12, 39 and 41 months, respectively. The other 3 patients underwent salvage chemotherapy after neck recurrence or distant metastasis, but disease progression occurred after 3, 21 and 43 months in the three cases.

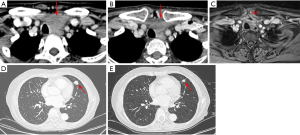

Two patients received immunotherapy combined with targeted therapy or chemotherapy, one as neoadjuvant therapy for advanced tumor and one as salvage therapy after lung metastases. One female patient with locally advanced tumor received neoadjuvant treatment with amilorotinib and camrelizumab (an anti-PD1 immunotherapeutic agent). After three cycles of treatment, she was evaluated as partial response (PR) with a tumor size reduction of 50%, thereby a radical tumor resection was followed successfully (Figure 6A-6C). Another patient with lung metastasis achieved PR after six cycles of camrelizumab combined with CEA regimen-based chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + etoposide). It was followed by camrelizumab as the maintenance treatment. After 22 months of follow-up, her tumor was still stable (Figure 6D,6E). These results suggested that immunotherapy and targeted therapy might be promising in advanced ITC.

Discussion

ITC is a rare malignant tumor with thymic epithelial differentiation that arises in the thyroid gland or perithyroidal soft tissue (5). There are some case reports, but few cohort studies about ITC so far. The knowledge of ITC’s diagnosis and prognosis is very limited, and the standard treatment for ITC has not been established. In several previous studies, ITC was reported to exhibit a relatively indolent biological behavior and a favorable prognosis (3,4,8,9,11-13). It is essential to distinguish ITC from more aggressive and negatively prognostic malignancies such as poorly differentiated, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, thyroid squamous cell carcinoma and metastatic carcinoma of extrathyroidal origins. However, preoperative examination for ITC has limited specificity, including imaging and cytology examinations (5,12). We presented a 43 ITC surgically-treated cohort for a better understanding about the clinical characteristics, prognosis, risk factors and optimal treatment modalities.

ITC is more commonly found in middle-aged women (3,4,14). In our series, the median age at initial diagnosis was 47 years (range, 29–63 years), and male: female ratio was 1.0:1.1. Because the tumors were mostly diagnosed at late stage, ITC seemed to be with larger tumor size and higher incidence of ETE than differentiated thyroid carcinoma. All cases were positive for CD5 and CD117 in our study. Positive CD5 and CD117 could play important role in the diagnosis of ITC. These findings are consistent with the clinical and pathological features of ITC reported in prior literature (3-6,15).

Because of the rarity of ITC, the optimal treatment strategy remains uncertain. At present, surgical removal is commonly regarded as the preferred approach for ITC (3,4,16,17). As reported previously, about half of the patients had regional lymphatic metastases (3,4). In our cohort of 43 patients with ITC, there were 30 patients who underwent prophylactic lymph node dissection. Among them, 5 patients were diagnosed with central lymph node metastasis pathologically. 10 patients who underwent therapeutic lymph node dissection were diagnosed with central/lateral/mediastinal lymph node metastasis pathologically. For patients with cN1, lymph node dissection of the appropriate region should be performed. For patients with cN0, we surpported that unilateral prophylactic central lymph node dissection should be performed.

We found that adjuvant radiotherapy had significant effect in improving local control rates, especially in advanced cases receiving palliative resection. Surgery plus radiotherapy could significantly improve survival and reduce regional recurrence of patients with ITC (3,4,11,14,17). In locally advanced disease, radical surgery often required removal of the involved tissue (such as trachea, esophagus) followed by reconstruction, which always represented a more destructive procedure (18). However, a case report of a locally advanced patient without surgical indications alternatively underwent radical radiotherapy with subsequent achievement of complete remission (7). If such a good local control with radiotherapy was proved further, it is debatable whether patients with locally advanced disease need radical surgery, which would drastically affect quality of life.

Chemotherapy was attempted in some patients with variable responses. However, the therapeutic efficacy of chemotherapy for ITC is unclear. As neoadjuvant therapy and salvage therapy, anti-PD-1 immunotherapy showed promising efficacy in ITC in our study. PD-L1 inhibitor (Pembrolizumab) was reported to achieve PR in a case with pleural metastasis of ITC (19).

ITC typically yields a favorable prognosis. After a mean follow-up of 74 months in our study, the 3-, 5- and 10-year PFS was 92.1%,59.8% and 52.3%, respectively, while the 3-, 5-, and 10-year DSS was 97.0%, 93.1% and 68.4%, respectively. Most of the distant metastases occurred 3 to 5 years after surgery. The most common site of metastasis is lung, followed by liver and bone. Ito et al. reported that the 5- and 10-year cause-specific survival rates were 90% and 82%, respectively (3).

Palliative resection, lymph node metastasis and Ki-67 labelling index were risk factors of ITC tumor progression. Lymph node metastasis has been reported to be associated with poor prognosis in ITC (3,4). The majority of patients with palliative resection were unable to radically remove the tumor due to the severe extension. Severe extension and high Ki-67 index usually indicates a more malignant tumor.

Our study described the clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis of ITC, and analyzed the risk factors of prognosis. There are some limitations. Due to the limited number of patients, there could be potential bias in the analysis. As a retrospective study, the analysis was also limited. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis with larger cohorts is still needed in the future.

Conclusions

Although ITC typically exhibits low-grade malignancy, it is still characterized by high tendency of lymph node and distant metastasis. Palliative resection and lymph node metastasis predict a worse prognosis. Radical surgery combined with radiotherapy would be applied as the optimal treatment currently, which would significantly improve local control. Immunotherapy and targeted therapies are potentially effective in advanced disease.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-2025-9/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-2025-9/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-2025-9/prf

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82002827 to T.Z.) and the medicine guidance project of the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai (grant No. 19411966600 to Y.W.).

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-2025-9/coif). T.Z. reports this study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82002827). Y.W. reports this study was supported by grants from the medicine guidance project of the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai (grant No. 19411966600). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (No. 050432-2108) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Miyauchi A, Kuma K, Matsuzuka F, et al. Intrathyroidal epithelial thymoma: an entity distinct from squamous cell carcinoma of the thyroid. World J Surg 1985;9:128-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baloch ZW, Asa SL, Barletta JA, et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms. Endocr Pathol 2022;33:27-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Nakamura Y, et al. Clinicopathologic significance of intrathyroidal epithelial thymoma/carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation: a collaborative study with Member Institutes of The Japanese Society of Thyroid Surgery. Am J Clin Pathol 2007;127:230-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao R, Jia X, Ji T, et al. Management and Prognostic Factors for Thyroid Carcinoma Showing Thymus-Like Elements (CASTLE): A Case Series Study. Front Oncol 2018;8:477. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okubo Y, Sakai M, Yamazaki H, et al. Histopathological study of carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE). Malays J Pathol 2020;42:259-65.

- Collins JA, Ping B, Bishop JA, et al. Carcinoma Showing Thymus-Like Differentiation (CASTLE): Cytopathological Features and Differential Diagnosis. Acta Cytol 2016;60:421-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kovářová P, Vojtíšek R, Krčma M, et al. Inoperable CASTLE of the thyroid gland treated with radical radiotherapy with complete remission. Strahlenther Onkol 2021;197:847-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao Y, Pan Y, Luo Y, et al. Intrathyroid thymic carcinoma: A clinicopathological analysis of 22 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol 2023;67:152221. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Hirokawa M, et al. Clinicopathological features and outcomes of intrathyroidal thymic carcinoma: a single institution study. Endocr J 2022;69:1351-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gurizzan C, Zamparini M, Volante M, et al. Outcome of patients with intrathyroidal thymic carcinoma: a pooled analysis. Endocr Relat Cancer 2021;28:593-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuroki M, Shibata H, Iinuma R, et al. A Case of Thyroid Carcinoma Showing Thymus-Like Differentiation With Breast Cancer Susceptibility Gene 2 Mutation: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2022;14:e30655. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tapescu I, Kohler A, Sangal NR, et al. Thyroid Malignancies With Thymic Differentiation: Outcomes of Rare SETTLE and CASTLE Tumors. Head Neck 2025;47:899-905. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liang J, Huang M, Huang H, et al. Intrathyroidal Thymic Carcinoma: A Retrospective Case Series Study. Ear Nose Throat J 2023;102:584-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao Q, Bian X. Two cases of concurrent carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE) coexisting with papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Surg Case Rep 2023;2023:rjad527. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dang NV, Son LX, Hong NTT, et al. Recurrence of carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE) involving the thyroid gland. Thyroid Res 2021;14:20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tran J, Zafereo M. Segmental tracheal resection (nine rings) and reconstruction for carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE) of the thyroid. Head Neck 2019;41:3478-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dong W, Zhang P, Li J, et al. Outcome of Thyroid Carcinoma Showing Thymus-Like Differentiation in Patients Undergoing Radical Resection. World J Surg 2018;42:1754-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fung ACH, Tsang JS, Lang BHH. Thyroid Carcinoma Showing Thymus-Like Differentiation (CASTLE) with Tracheal Invasion: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep 2019;20:1845-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lorenz L, von Rappard J, Arnold W, et al. Pembrolizumab in a Patient With a Metastatic CASTLE Tumor of the Parotid. Front Oncol 2019;9:734. [Crossref] [PubMed]