Breast tuberculosis with bone destruction mimicking breast cancer with bone metastasis: a case report and literature review

Highlight box

Key findings

• We report a case of breast tuberculosis (BTB) with bone destruction mimicking breast cancer with bone metastasis.

What is known and what is new?

• The incidence of BTB is low and it is easy to be misdiagnosed. Especially, BTB accompanied by bone destruction is easily misdiagnosed as breast cancer. BTB is usually treated with anti-tuberculosis (TB) drugs, and surgery is only a small part of the treatment.

• The diagnosis and management of this case have been complex. Following 4 months of treatment with anti-TB medications, the patient underwent surgical intervention after a thorough professional assessment, subsequently continuing anti-TB therapy, yielding favorable outcomes without any indications of recurrence.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• It is challenging to distinguish BTB from other diseases, such as breast cancer and granulomatous lobulitis. BTB is associated with bone destruction and is easily confused with breast cancer with bone metastasis. The clinicians should thoroughly inquire about the patient’s history of TB exposure. The BTB should be considered when the disease course is prolonged, nonresponsive to anti-inflammatory therapy, and associated with a long-term inflammation.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a significant global health issue and ranks as the second leading cause of infectious disease mortality worldwide (1). Breast TB (BTB), accounts for a small proportion, ranging from 0.025% to 0.1%, of all TB cases (2). In elderly patients, BTB may present in a very similar way to breast cancer with bone metastasis. However, young patients typically present with suppurative abscesses, which can be challenging to differentiate from granulomatous lobulitis. The diagnosis of BTB is very important because it determines the appropriate follow-up treatment. We present a case of BTB with bone destruction, initially misdiagnosed as breast cancer with bone metastasis. We present this article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-24-185/rc).

Case presentation

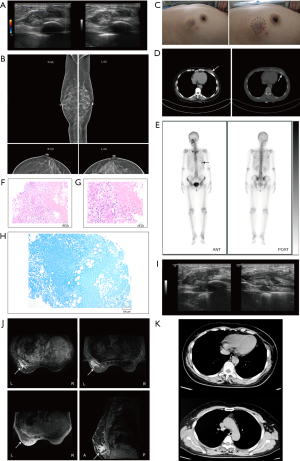

A 52-year-old woman in menopause was admitted with painful “left breast lump for 20 days”. The skin on the surface of the mass was not red, swollen, or ruptured, and there was no discharge of the left nipple. The patient then went to a township hospital and was diagnosed with a left breast tumor, suggesting further examination. Later, the patient was admitted to Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, and ultrasound showed a mixed-echo mass with an irregular shape and unclear boundaries, measuring 4.1 cm × 1.4 cm, located deep in the subcutaneous tissue of the left breast at the 6 o’clock position (Figure 1A). Additionally, mammography showed scattered calcifications below the left breast (Figure 1B). It was recommended that the patient be admitted to Qilu Hospital of Shandong University with left mammary duct ectasia. The patient had recently had good diet and sleep, normal stool and urine, and no significant change in weight. The patient denied a history of chronic diseases such as hypertension. The patient denied the history of TB infection and any history of TB exposure. The patient denied the history of blood transfusion, trauma, surgery, and allergies.

Upon admission, the patient exhibited stable vital signs and did not present with cough, fever, night sweats, weight loss, or any other systemic symptoms. A pliant nodule was palpated below the left breast, approximately 3 cm from the areola at the 6 o’clock position (Figure 1C), with an irregular shape, unclear boundary, rough surface, and limited mobility. No notable abnormalities were detected in the lymph nodes. Blood tests showed the patient’s inflammatory marker, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), was elevated (39.00 mm/h). The proportion of white blood cells in the patient’s blood routine was normal. Chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a soft tissue density mass lesion at the lower margin of the left mammary gland, measuring approximately 3.6 cm in length, accompanied by bone destruction near the ribs, and CT showed no sign of pulmonary TB (Figure 1D). Emission CT (ECT; whole-body bone imaging) demonstrated enhancement of the sixth anterior rib strip, suggesting the possibility of bone metastasis (Figure 1E). Therefore, the patient was clinically diagnosed with breast cancer accompanied by bone metastasis. Subsequently, a core needle biopsy of the left breast mass was performed with real-time ultrasound guidance and a rapid paraffin section examination was conducted. The hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining showed chronic inflammation with granulomatous inflammation and extensive necrosis, suggesting a possible diagnosis of TB (Figure 1F,1G). Acid-fast staining did not detect any specific pathogens (Figure 1H). Considering the likelihood of BTB, an anti-TB antibody (TB-Ab) test yielded a negative result. However, T cells spot test (T-SPOT) yielded positive results. Breast ultrasound suggested an inflammatory mass with possible abscess formation on the left chest wall (Figure 1I). Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed irregular lesions in the deepest part of the glands in the lower outer quadrant of the left breast. Enhanced MRI revealed annular enhancement, with the lesions extending into the chest wall, causing rib destruction and thickening of the adjacent pleura (Figure 1J). Based on the above physical examination, test results, and imaging studies, the patient was diagnosed with BTB combined with bone destruction. Therefore, the patient was admitted to Shandong Public Health Clinical Center. Upon admission, breast lesions were subjected to biopsy, and subsequent polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of the aspirated specimens confirmed the presence of DNA from the Mycobacterium TB complex group, along with genes associated with rifampicin resistance. No malignant tumor cells were detected in the needle aspiration cytology smear of the breast lesion. Consequently, she was formally diagnosed with BTB accompanied by rib bone destruction and received first-line anti-TB treatment with HRZE (H: isoniazid, R: rifampicin, Z: pyrazinamide, E: ethambutol) for 4 months. Later, in March 2023, the patient underwent surgical intervention, which included excision of the left breast lesion, resection of the tuberculous lesion in the left chest wall, partial rib resection, and breast reconstruction utilizing a left latissimus dorsi flap. The patient’s intraoperative frozen-section examination showed that the left breast mass was an inflammatory lesion, and necrotizing granuloma was found. The patient’s postoperative routine paraffin pathology revealed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of the left breast mass and positive acid-fast staining. The fibrous connective tissue on the surface of the diseased rib showed chronic inflammation. She received first-line anti-TB treatment with HRZE. Nine months after surgery, the patient’s breast ultrasound, chest CT (Figure 1K), breast MRI, and blood tests showed no signs of BTB recurrence.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

TB is a significant global health concern and ranks as the second leading cause of death from infectious diseases (1). TB most often occurs in the lungs, and various sequelae and complications of intrapulmonary tissue or extrapulmonary tissue threaten human health (3,4). BTB accounts for a small proportion, ranging from 0.025% to 0.1%, of all TB cases (2,5), occurs in women of childbearing age, with an average age of 32.2 to 40 years (6).

Primary BTB is uncommon (7), with the bacteria entering the breast through the opening of the duct or via damage to the breast skin (8). The secondary BTB is more frequently encountered through three modes of infection: neighboring tissues and organs, lymphatic dissemination and hematogenous dissemination. Among these, lymphatic transmission is the most common (9). There are five types of BTB: nodular, disseminated, sclerosis, obliterated, and acute miliary (9). Elderly patients often present with the nodular type, which shares similarities with breast cancer according to physical and imaging examinations, leading to potential misdiagnosis of BTB as breast cancer (2,10-14) (Table 1, only the literatures published after 2020 are presented in Table 1 and subsequent tables). It should be noted that the coexistence of breast cancer and the BTB is also possible (15-17) (Table 2). Conversely, young patients tend to exhibit suppurative abscesses, which can be challenging to distinguish from granulomatous lobulitis (18).

Table 1

| Age (years old)/sex | Type of BTB | Clinical picture | Auxiliary inspection | Prediagnosis treatment | Diagnostic method | Treatment | Follow-up visit | Cite | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local expression | System expression | ||||||||

| 56/F | P | There is a lump and a superficial ulceration of the skin over the upper outer quadrant of the breast | Weight loss and loss of appetite | The preliminary diagnosis was breast cancer. A core-needle biopsy and histopathological examination of the lump revealed caseating granulomas with multinucleate giant cells; ZN staining (+); AFB (+) | N/A | Histopathological examination + ZN staining + AFB | 6HRZE | Relapse-free | (11) |

| 29/F | N/A | Two discrete and tender masses were palpable in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast | N/A | Physical examination and ultrasound made a preliminary diagnosis of breast cancer | Take antibiotics and pain relievers | An excision biopsy and pathological examination: numerous granulomas with central caseous necrosis; Mantoux test (+) | 6HRZE | Loss to follow-up | (12) |

| 31/F | N/A | A palpable, tender mass in her left breast, with pain, swelling and purulent discharge | N/A | Mammography: lobulated heterogeneously hypoechoic lesion suggesting inflammatory/infective. Ultrasound-guided FNAC: ductal malignancy with abscess | Take antibiotics + mastectomy + abscess drainage | Histopathological examination: granulomatous mastitis. Tumor excision biopsy: chronic granulomatous inflammation and there was no evidence of carcinoma | 6HRZE | Relapse-free | (13) |

| 37/F | P | A palpable mass in left breast, with retraction and ulceration of the skin, pain and redness | N/A | Both ultrasound and mammography suspect breast cancer | N/A | Excise the diseased tissue and the histopathological examination: granulomatous caseating tuberculous mastitis | After 1HRZE, the patient did not adhere to treatment, so relapsed 3 months later. We performed another lumpectomy + 9HRZE | Relapse-free | (14) |

BTB, breast tuberculosis; F, female; P, primary; ZN, Ziehl-Neelsen; AFB, acid fast bacilli; (+), positive; 6HRZE, 6 months of HRZE treatment; H, isoniazid; R, rifampicin; Z, pyrazinamide; E, ethambutol; N/A, not applicable; FNAC, fine needle aspiration cytology; 1HRZE, 1 month of HRZE treatment; 9HRZE, 9 months of HRZE treatment.

Table 2

| Age (years old)/sex | Type of BTB | Clinical picture | Auxiliary inspection | Prediagnosis treatment | Diagnostic method | Treatment | Follow-up visit | Cite | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local expression | System expression | ||||||||

| 70/F | N/A | Right breast mass with pain | N/A | Mammography: skin thickening of the areola and the nipple | N/A | A tru-cut biopsy: an invasive ductal carcinoma of no special type along with evidence of non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. AFB (+) | ATT + radical mastectomy with lymphadenectomy | Not mentioned | (16) |

| 45/F | N/A | Left breast mass with pain | A history of incomplete ATT for tubercular lymphadenitis | Mammography: a small opacity with few micro calcifications in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast suggestive of breast carcinoma | N/A | FNAC: clusters of malignant duct epithelial cells and many epithelioid cell granulomas and caseous necrosis | ATT + modified radical mastectomy | Not mentioned | (17) |

BTB, breast tuberculosis; F, female; N/A, not applicable; AFB, acid fast bacilli; (+), positive; ATT, antitubercular therapy; FNAC, fine needle aspiration cytology.

Only a small proportion of patients with BTB exhibit symptoms of systemic TB (19), such as low-grade fever, night sweats, and weight loss. This patient had no systemic symptoms, as described above. The most common presentation is unilateral, solitary, and indistinct hard mass in the breast, primarily located in the central or outer upper quadrant (20). The nodules in this patient were located below the left breast and were irregular in shape, with unclear borders, rough surfaces, and limited movement. Axillary lymph node enlargement can be observed in 50% to 75% of patients (14). No axillary or supraclavicular lymphadenopathy was detected in this patient. As the disease progresses, it may extend to the skin, resulting in edema adhesion, and leading to ulcers, fistulas, or sinus tracts (21-23). The BTB can invade bone and cause bone destruction (Table 3) (24-27). This patient had primary BTB with bone destruction and was initially misdiagnosed with breast cancer with bone metastasis.

Table 3

| Age (years old)/sex | Type of BTB | Clinical picture | Auxiliary inspection | Prediagnosis treatment | Diagnostic method | Treatment | Follow-up visit | Cite | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local expression | System expression | ||||||||

| 21/F | S | Two sinuses in the right breast, spontaneous discharge of pus | N/A | Mantoux test (+); X-ray chest: an osteolytic lesion in anterior part of fifth rib; breast ultrasound: ill-defined sinus tract and opening | Irregularly ATT | Histopathology of specimen: chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, with areas of caseous necrosis, giant cells | 9HRZE + resection of lesions and ribs | Relapse-free | (24) |

| 40/F | P | A soft fluctuant swelling in the upper inner quadrant of left breast | Associated low-grade fever with night sweats and evening rise of temperature | FNAC of the swelling: tubercular cold abscess; ZN staining of pus (+); AFB (+); after ATT of 1 month, patient has swelling and sinuses above the sternum. X-ray chest with contrast injected through the sinus: osteomyelitic changes in the sternum with a cavity | N/A | FNAC + AFB | 3HERZ + 9HR + debridement and curettage of osteomyetic bone | Relapse-free | (25) |

| 11/M | P | Gradual left breast enlargement for 1 year duration, a firm swelling involving left anterior chest wall elevating the nipple and areolar region | N/A | Ultrasound examination: a thick wall cystic lesion with internal debris and bone erosion. Ultrasound examination: a thick wall cystic lesion with internal debris and bone erosion with a similar cystic lesion in the substernal area through a hole in the fifth rib | N/A | Excise the diseased tissue and ribs and the histopathological examination: multiple granuloma with caseating material | 3ATT + excise the diseased tissue and ribs | Relapse-free | (26) |

| 42/F | N/A | Palpable cord-like induration with mild tenderness from the right margin of the sternum to the skin around the right nipple. A fistula near the right nipple, and it showed slightly cloudy and yellowish exudates | Miliary TB at the age of 25 years | Mammography: regional microcalcifications. MRI: a fistula formation between the parasternal area and skin of the right breast. T2 imaging: enhanced high signal intensity lesions in the sternum, suggesting sternal osteomyelitis | Broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment + incisional drainage of the lesion | PCR of the pus for M. TB (+) and the M. TB isolate was cultured from the pus specimen | 2HRZE + 7HR | Relapse-free | (27) |

BTB, breast tuberculosis; F, female; M, male; S, secondary; P, primary; N/A, not applicable; (+), positive; ATT, antitubercular therapy; 9HRZE, 9 months of HRZE treatment; H, isoniazid; R, rifampicin; Z, pyrazinamide; E, ethambutol; FNAC, fine needle aspiration cytology; ZN, Ziehl-Neelsen; AFB, acid fast bacilli; 3HRZE, 3 months of HRZE treatment; 9HR, 9 months of HR treatment; 3ATT, 3 months of antitubercular therapy; TB, tuberculosis; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; M. TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; 2HRZE, 2 months of HRZE treatment; 7HR, 7 months of HR treatment.

Auxiliary examinations for the BTB include bacteriology, imaging, pathology, immunology, and molecular biology (28,29). Among these methods, Mycobacterium TB culture and Ziehl-Neelsen staining serve as the gold standards for diagnosing TB infection, offering high specificity but limited sensitivity. Acid-fast staining was negative in this patient. Conventional ultrasound allows for observation of the lesion’s location, shape, boundary, internal echo, calcification, and blood supply. Additionally, ultrasound provides clear visualization of sinus tract formation (30). Breast MRI aids in visualizing mass sinus formation and assessing the extent of lesion involvement in surrounding tissues. MRI of this case not only revealed deep irregular lesions of the gland, involving the chest wall and ribs backwards, but the enhanced scan also showed annular enhancement. Granulomatous lesions with caseous necrosis are the characteristic pathological features of BTB and can be distinguished from granulomatous lobulitis. The purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test, T-SPOT TB test for TB infection, and TB-Ab test have been utilized as primary screening tests for TB patients. TB-Ab test is not universally acknowledged due to insufficient sensitivity and specificity. This is because there are false negatives and false positives (31). People vaccinated with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Vaccine will show false positive results for TB-Ab, while immunocompromised TB patients will show false negative results for TB-Ab. The T-SPOT test has emerged as a valuable tool for diagnosing extrapulmonary TB (32). It is primarily utilized to differentiate the BTB from other forms of granulomatous mastitis (7).

There are no specific guidelines for the treatment of BTB, and some publications report the application of standard TB treatment, a four-drug strategy of rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for 2 months, followed by a two-drug rifampicin and isoniazid for 6 to 7 months (1). Some cases have also been reported that require extension up to 18 months due to poor clinical response (19). Mastectomy has been performed in 4% of cases, representing 4.5% of all breast surgeries in developing countries (1).

Conclusions

Here, the patient, a middle-aged woman, presented with a breast mass. Imaging revealed bone destruction, leading to an initial diagnosis of breast cancer with bone metastasis. After the biopsy at Shandong Public Health Clinical Center, the PCR of the lesion detected TB DNA, which confirmed the diagnosis of BTB. Subsequent surgical intervention and anti-TB therapy were performed, resulting in effective symptom control without recurrence. BTB is characterized by a low incidence, nonspecific imaging findings, and laboratory examinations that can be influenced by various factors. This can make it challenging to differentiate BTB from other conditions such as breast cancer, granulomatous lobulitis, or breast fibroadenoma. Needle biopsy and empirical anti-TB therapy are valuable diagnostic approaches for the BTB, and clinicians should thoroughly inquire about the patient’s history of TB exposure. The BTB should be considered when the disease course is prolonged, nonresponsive to anti-inflammatory therapy, and associated with a long-term inflammation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Michael N. Routledge (University of Leicester) and Prof. Yun Yun Gong (University of Leeds) for language editing and valuable comments.

Funding: This work was supported by

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-24-185/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-24-185/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-24-185/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Sinha R. Rahul. Breast tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc 2019;66:6-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalaç N, Ozkan B, Bayiz H, et al. Breast tuberculosis. Breast 2002;11:346-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim HY, Song KS, Goo JM, et al. Thoracic sequelae and complications of tuberculosis. Radiographics 2001;21:839-58; discussion 859-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Palma A, Maruccia M, Di Gennaro F. Right thoracotomy approach for treatment of left bronchopleural fistula after pneumonectomy for tubercolosis. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020;68:1539-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Onaghinor IJ, Achusi IB, Ariyo OE. Tuberculosis of the breast: a rare extra-pulmonary presentation of tuberculosis. J Infect Dev Ctries 2024;18:1141-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kilic MO, Sağlam C, Ağca FD, et al. Clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic management of patients with breast tuberculosis: Analysis of 46 Cases. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2016;32:27-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tewari M, Shukla HS. Breast tuberculosis: diagnosis, clinical features & management. Indian J Med Res 2005;122:103-10.

- Kao PT, Tu MY, Tang SH, et al. Tuberculosis of the breast with erythema nodosum: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2010;4:124. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baharoon S. Tuberculosis of the breast. Ann Thorac Med 2008;3:110-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- da Silva BB, Dos Santos LG, Costa PV, et al. Primary tuberculosis of the breast mimicking carcinoma. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005;73:975-6.

- Khandelwal R, Jain I. Breast tuberculosis mimicking a malignancy: a rare case report with review of literature. Breast Dis 2013;34:53-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sabageh D, Amao EA, Ayo-Aderibigbe A A, et al. Tuberculous mastitis simulating carcinoma of the breast in a young Nigerian woman: a case report. Pan Afr Med J 2015;21:125. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feroz W, Sheikh AMA, Mugada V. Tubercular Mastitis Mimicking as Malignancy: A Case Report. Prague Med Rep 2020;121:267-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kayali S, Alhamid A, Kayali A, et al. Primary Tuberculous Mastitis: The first report from Syria. Int J Surg Case Rep 2020;68:48-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tulasi NR, Raju PC, Damodaran V, et al. A spectrum of coexistent tuberculosis and carcinoma in the breast and axillary lymph nodes: report of five cases. Breast 2006;15:437-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bouti K, Soualhi M, Marc K, et al. Postmenopausal breast tuberculosis - report of 4 cases. Breast Care (Basel) 2012;7:411-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui B, Akhter K, Faridi SH, et al. A case of coexisting carcinoma and tuberculosis in one breast. J Transl Int Med 2015;3:32-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nguyen MH, Molland JG, Kennedy S, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: case series and clinical review. Intern Med J 2021;51:1791-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quaglio G, Pizzol D, Isaakidis P, et al. Breast Tuberculosis in Women: A Systematic Review. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2019;101:12-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jalali U, Rasul S, Khan A, et al. Tuberculous mastitis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2005;15:234-7.

- Pimentel Nunes M, Branco Carvalho I, Araújo I, et al. Breast Tuberculosis: A Case Report. Cureus 2023;15:e34175. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boland-Rodríguez E, Parra-Herrera JL, Romero-González I. Tuberculous Mastitis. JAMA Dermatol 2024;160:888. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Molla YD, Iberahim MA, Alemu HT, et al. Bilateral breast tuberculosis: A case report. Clin Case Rep 2024;12:e8826. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wani I, Lone AM, Malik R, et al. Secondary tuberculosis of breast: case report. ISRN Surg 2011;2011:529368. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakhshi GD, Shenoy SS, Jadhav KV, et al. Tuberculous osteomyelitis of sternum secondary to primary tuberculous mastitis. Clin Pract 2014;4:656. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kakamad FH, Hassan MN, Salih AM, et al. Primary chest wall tuberculosis mimicking gynecomastia: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2020;75:473-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sagara Y, Hatakeyama S, Kumabe A, et al. Breast tuberculosis presenting with intractable mastitis: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2021;15:101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baykan AH, Sayiner HS, Inan I, et al. Primary breast tuberculosis: imaging findings of a rare disease. Insights Imaging 2021;12:19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jain R, Gupta G, Mitra DK, et al. Diagnosis of extra pulmonary tuberculosis: An update on novel diagnostic approaches. Respir Med 2024;225:107601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allan-Blitz LT, Yarbrough C, Ndayizigiye M, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for diagnosing extrapulmonary TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2024;28:217-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Araujo LS, da Silva NBM, Leung JAM, et al. IgG subclasses' response to a set of mycobacterial antigens in different stages of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2018;108:70-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai CC, Tan CK, Liu WL, et al. Diagnostic performance of an enzyme-linked immunospot assay for interferon-γ in skeletal tuberculosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2011;30:767-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]