Lumboabdominal migration of injected polyacrylamide hydrogel following breast augmentation: a case report and literature review

Highlight box

Key findings

• We report a rare case of a patient with distant migration of fillers after polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAAG) injection for breast augmentation.

What is known and what is new?

• PAAG migration is a common complication after injection, and the main areas of migration include chest wall migration and abdominal wall migration. The main surgical methods currently reported involve making several incisions to thoroughly remove the filling material and the capsule, but this affects aesthetics.

• The patient underwent surgery to extract the breast augmentation material from the lumboabdominal wall and breasts, followed by a robot-assisted excision of the lumboabdominal wall capsule and immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The capsule should be completely and thoroughly excised, and strategically concealing the scars is crucial to beautiful shape.

Introduction

Polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAAG) is a stable, nontoxic and nonbiodegradable hydrogel composed of polyacrylamide and water for injection in a specific proportion (1). In the 1980s, PAAG was widely used in biomedical research and for breast augmentation and facial corrections in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union (2). In 1997, it was approved for using in restoring contours in China and subsequently became popular for facial depression, limb deformity, and breast augmentation in local hospitals and private beauty clinics (3). Despite the immediate effects of PAAG injection in breast augmentation, numerous late complications have been observed, including breast lumps, inflammation, firmness, disfigurement, displacement, migration, unrest, and pain (3-5).

A case was reported where a woman who underwent breast augmentation with PAAG experienced increased breast size, pain, and difficulty breastfeeding during pregnancy, leading to a mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction (6). Additionally, cases of breast cancer following PAAG injection have been reported (7-10). Although the Chinese State Food and Drug Administration prohibited the production, sale, and use of PAAG in 2006 (10,11), many women had already received PAAG injection, leading to long-term complications over a considerable period of time. PAAG migration is a common complication, but distant migration is relatively rare, with only a few cases reported (12). Currently, treatments for large cavities caused by PAAG migration often involve several incisions to thoroughly clear the filler and capsule (13). However, this approach would result in increased incision scars and potentially compromising aesthetic outcomes. This case report presents a lumboabdominal migration following breast PAAG injection and the treatment approach used. We present this case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-24-311/rc).

Case presentation

Patient

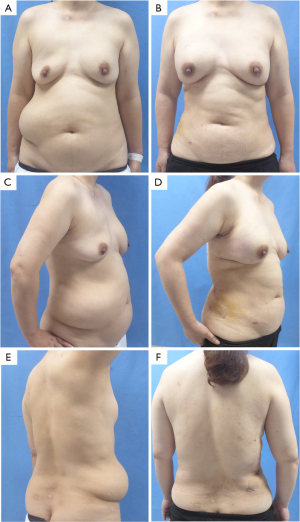

A 51-year-old patient presented with a large, fluctuating mass in the right-sided lumboabdominal region for one year. She had undergone bilateral breast augmentation with PAAG injection 18 years prior. The lumboabdominal mass spanned approximately 35 cm × 20 cm, with ill-defined edges and a soft texture (Figure 1). The breasts were asymmetrical, with the right breast sagging and the left breast being hard in texture (Figure 1). The patient has not received any prior therapeutic treatments. A chest computerized tomography (CT) scan indicates that the breast augmentation material on the left side was significantly more pronounced than on the right side, with multiple leaks in the subcutaneous area of the anterior chest wall (Figure 2). An abdominal CT scan revealed several abnormal densities in the abdominal wall, likely to be breast augmentation material (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with distant migration of breast implant material. Following thorough expert consultation and patient’s consent, the decision was made to perform an extraction of the breast augmentation material from the lumboabdominal wall and breasts, along with a robot-assisted excision of the lumboabdominal wall capsule and closure of the fistula. The treatment plan also included the immediate breast reconstruction with prosthesis and mesh.

Operative methods

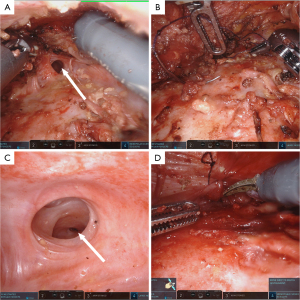

Preoperatively, the approximate area for waist and abdomen surgery was delineated with the patient in a standing position (Figure 3). Following general anesthesia, the patient was repositioned into the lateral decubitus position (Figure 3), and the surgical site was disinfected and prepared. A solution of epinephrine saline was injected into the cavity where the PAAG was densely localized. A metal suction tip with lateral apertures was employed to meticulously scrape and aspirate the fillers. Throughout the procedure, the solution was extricated (Figure 3), and the cavity was meticulously irrigated and suctioned. A transverse incision, approximately 5 cm in length, was performed at the anterior superior iliac spine. After dissecting through the subcutaneous tissue to expose the capsule, a single-port skin retractor was introduced, and cover it with a sterile glove. The tips of the glove fingers were cut off, and two trocars were inserted; an additional trocar was placed on the lateral incision (Figure 3). A subcutaneous tunnel was fashioned, converging at three points, and the laparoscope, Maryland bipolar forceps, and monopolar coagulation scissors were deployed, completing the robotic interface. The PAAG capsule in the lumboabdominal region was meticulously and thoroughly excised (Figure 3). The patient was then repositioned to a supine position, and the surgical area was disinfected and prepared. Incisions of approximately 5 cm were made in both axillary regions, where the breast PAAG in both breasts was carried out using the same method described above. A single-port was inserted into the axillary incision, with two trocars in place; a third port was established via a 1 cm incision along the midaxillary line, level with the nipple, to introduce an additional trocar. Residual PAAG nodules anterior and posterior to the pectoral muscles were meticulously cleared. A sinus tract was found, approximately 1.5 cm in diameter, connecting the right and left breast implant cavities anterior to the sternum (Figure 4). This tract was subsequently sutured and sealed (Figure 4). Post-irrigation, 180 cc prostheses were implanted within both breast cavities to achieve the desired contour, and the postoperative breast morphology was notably improved compared to the preoperative state (Figure 5). The postoperative pathological examination of the abdominal wall capsule suggested fibroblast proliferation and hyaline degeneration, with a few blue-stained amorphous substances accompanied by a foreign body giant cell reaction (Figure 6). One-month postoperative views were presented in Figure 1.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Hydrophilic polyacrylamide, a non-absorbable synthetic polymer derived from polymerization of acrylamide monomers, was considered to maintain breast softness and pliability after injection and favored by women because it was a simple operation (14). However, acrylamide has been proven to be a neurotoxin in humans and has been confirmed as a potential carcinogen in animal testing (15). Animal studies involving subcutaneous injection of PAAG in rats have demonstrated significant cytotoxicity (16). Many women have experienced both immediate and long-term complications following the injection of PAAG, including the migration of fillers, infections, lumps, difficulties in breastfeeding, and even the development of breast cancer (8,17,18). Despite the China Food and Drug Administration’s prohibition on PAAG injection nearly two decades ago, complications arising from PAAG injections remain prevalent, causing considerable distress to patients. The current conventional surgical methods for treating PAAG-injection complications involve the removal of PAAG followed by debridement or capsulectomy, and in some cases, partial pectoralis muscle resection, partial or total mastectomy, and breast reconstruction (19,20).

PAAG migration is a common complication after injection, with various mechanisms involved, including gravity and muscle activity, which can cause the fibrous capsule surrounding the injected material to thin and rupture, leading to migration through subcutaneous tissues or tissue spaces. After breast augmentation with PAAG, the main areas of migration include chest wall migration, abdominal wall migration, and even vulvar migration (13,21). Our patient discovered the right-sided lumboabdominal lump approximately 17 years after augmentation mammoplasty, and the specific time when the filler began to migrate was unknown. Reports of extensive migration of breast fillers like our case are relatively rare. PAAG migration of breast fillers can often be detected through imaging examination, but some patients opt not to undergo treatment because it has not affected their daily life or due to economic factors (22,23). However, from both aesthetic and health perspectives, surgical intervention should be considered. For patients with distant migration of the filler, several incisions should be made at the sites where fillers are migrated to remove the filler as much as possible, and surrounding capsule tissue should be thoroughly excised, achieving rapid tissue healing (13,20). However, multiple incisions can lead to an excessive amount of scarring, especially when the migration occurs in areas such as the chest and abdominal walls, where scars are more pronounced and can affect aesthetics (24).

The patient we reported had extensive migration of the breast fillers to the lumboabdominal wall. If the traditional surgical incision method is followed, the scar would be long and conspicuous. Robot-assisted surgery offers several advantages, including seven degrees of freedom, tremor elimination, 3D magnified vision, ergonomic positioning, and enhanced resolution, which can improve surgical techniques limited by human anatomy (25). The freedom and precision of movement afforded by the robotic assistance system have led to its rapid application across various medical departments (26). In this case report, in order to expand the surgical operating space and prevent the rupture of the capsule wall during surgery, which could lead to the leakage of PAAG and affect the surgical view, we first aspirated the breast augmentation agent before performed a robot-assisted PAAG capsulectomy of the lumboabdominal region. The capsule was completely and thoroughly excised, and the incision was strategically concealed in an area that can be covered by pants. Moreover, the sinus tract between the left and right breasts was also discovered and closed under robotic assistance. We did not find a sinus tract between the right breast and the right-sided lumboabdominal region, possibly due to prolonged healing or other reasons. To prevent the potential for future implant displacement that could result from tissue laxity between the patient’s right breast and lumboabdominal wall caused by an inframammary fold incision, and considering aesthetics, we chose to make the incision between the outer edge of the pectoralis major muscle and the anterior edge of the latissimus dorsi muscle, two fingerbreadths below the axillary crease, to perform the breast surgery. The retrospective study by Trignano et al. explored the immediate implant breast reconstruction following the removal of hyaluronic acid cysts due to complications in patients who had undergone hyaluronic acid breast augmentation and all patients achieved good aesthetic outcomes (27). In this case report, the patient is satisfied with the incision on their abdomen and rated that the shape of their breasts has also improved significantly.

Long-distance migration of PAAG is a rare and complex problem that requires an individualized treatment plan. Understanding the migration patterns of breast fillers and their associated complications is crucial for effective diagnosis and treatment. For patients experiencing extensive migration of fillers, the precision and flexibility offered by robot-assisted surgery can significantly minimize tissue damage and reduce scarring.

Conclusions

This case report describes the right-sided lumboabdominal migration of breast fillers following PAAG injection. The patient underwent extraction of the breast augmentation material from the lumboabdominal wall and breasts, along with a robot-assisted excision of the lumboabdominal wall capsule and prosthetic breast reconstruction. The patient was satisfied with the abdominal scarring and the reconstructed breasts, which was crucial to the success of this procedure. Further follow-up is needed to determine the long-term effects.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-24-311/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-24-311/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-24-311/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Christensen LH, Breiting VB, Aasted A, et al. Long-term effects of polyacrylamide hydrogel on human breast tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003;111:1883-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Breiting V, Aasted A, Jørgensen A, et al. A study on patients treated with polyacrylamide hydrogel injection for facial corrections. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2004;28:45-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei W. Treatment of complications from polyacrylamide hydrogel breast augmentation. Exp Ther Med 2016;12:173-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen B, Song H. Management of Breast Deformity After Removal of Injectable Polyacrylamide Hydrogel: Retrospective Study of 200 Cases for 7 Years. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2016;40:482-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trignano E, Baccari M, Pili N, et al. Complications after breast augmentation with hyaluronic acid: a case report. Gland Surg 2020;9:2193-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin WC, Hsu GC, Hsu YC, et al. A late complication of augmentation mammoplasty by polyacrylamide hydrogel injection: ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging findings of huge galactocele formation in a puerperal woman with pathological correlation. Breast J 2008;14:584-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng NX, Liu LG, Hui L, et al. Breast cancer following augmentation mammaplasty with polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAAG) injection. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2009;33:563-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao Y, Yuan NA, Li K, et al. Bilateral breast cancer following augmentation mammaplasty with polyacrylamide hydrogel injection: A case report. Oncol Lett 2015;9:2687-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen G, Wang Y, Huang JL. Breast cancer following polyacrylamide hydrogel injection for breast augmentation: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol 2016;4:433-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang Y, Li S, He J, et al. Clinicopathological Analysis of 90 Cases of Polyacrylamide Hydrogel Injection for Breast Augmentation Including 2 Cases Followed by Breast Cancer. Breast Care (Basel) 2020;15:38-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ding F, Zhao F, Jin R, et al. Management of Complications in 257 Cases of Breast Augmentation with Polyacrylamide Hydrogel, using Two Different Strategies: A Retrospective Study. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2022;46:2107-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Son MJ, Ko KH, Jung HK, et al. Complications and Radiologic Features of Breast Augmentation via Injection of Aquafilling Gel. J Ultrasound Med 2018;37:1835-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wen J, Li Z, Chi Y, et al. Vulvar migration of injected polyacrylamide hydrogel following breast augmentation: a case report and literature review. BMC Womens Health 2024;24:152. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leung KM, Yeoh GP, Chan KW. Breast pathology in complications associated with polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAAG) mammoplasty. Hong Kong Med J 2007;13:137-40.

- Amended final report on the safety assessment of polyacrylamide and acrylamide residues in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol 2005;24:21-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huo M, Huang J, Qi K. Experimental study on the toxic effects of hydrophilic polyacrylamide gel. Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi 2002;18:79-80.

- Jin R, Luo X, Wang X, et al. Complications and Treatment Strategy After Breast Augmentation by Polyacrylamide Hydrogel Injection: Summary of 10-Year Clinical Experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2018;42:402-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ebisudani S, Inagawa K, Suzuki Y, et al. Unilateral Breast Inflation Caused by Breastfeeding after Polyacrylamide Hydrogel Injection. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2021;9:e3335. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang P, Ng SL. Delayed complications from polyacrylamide gel breast fillers: a case report. J Surg Case Rep 2024;2024:rjae095. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Unukovych D, Khrapach V, Wickman M, et al. Polyacrylamide gel injections for breast augmentation: management of complications in 106 patients, a multicenter study. World J Surg 2012;36:695-701. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi JY, Choi YJ, Jung SN, et al. Abdominal displacement of breast filler after previous trans-umbilical breast augmentation (TUBA): a case report. Gland Surg 2023;12:1131-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi YJ, Lee IS, Song YS, et al. Distant migration of gel filler: imaging findings following breast augmentation. Skeletal Radiol 2022;51:2223-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang B, Sun J, Tong J. Breast contracture and skin sclerosis following 20 years of polyacrylamide hydrogel migration in a patient with familial vitiligo: a case report. BMC Surg 2021;21:104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu J, Zhang X, Zhao Q, et al. Vacuum sealing drainage in the treatment of migrated polyacrylamide hydrogel after breast augmentation: a case report. Breast Care (Basel) 2014;9:273-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen K, Zhang J, Beeraka NM, et al. Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Breast Surgery: Recent Evidence with Comparative Clinical Outcomes. J Clin Med 2022;11:1827. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cianchi F. Robotics in general surgery: a promising evolution. Minerva Surg 2021;76:103-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trignano E, Rusciani A, Armenti AF, et al. Augmentation Mammaplasty After Breast Enhancement With Hyaluronic Acid. Aesthet Surg J 2015;35:NP161-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]