Primary and secondary angiosarcoma of the breast

Introduction

Angiosarcoma (AS) of the breast is rare, accounting for 1% of all soft tissue breast tumors (1). It presents as primary tumors of the breast or as secondary lesions that are most commonly associated with previous radiotherapy. Primary AS has been observed in women age 30-50 years presenting with poorly defined masses. It accounts for 1-3). In contrast, secondary AS presents in older women (median age 67-71 years) following a median of 10.5 years after radiotherapy for breast cancer (1,4-6). The median latency to presentation after radiotherapy in seven series ranges from 5 to 10 years (1). Although a causal relationship between radiation exposure and AS has not been established, multiple case reports support the increased risk for AS following adjuvant radiotherapy (7-9). It has been proposed that at radiation doses >50 Gy apoptosis occurs while at 4,5). When associated with chronic lymphedema and outside a radiated field, AS in an edematous limb after mastectomy and radiotherapy is referred to as Stewart-Treves syndrome (1,3).

Since the first case of breast AS was presented in 1907 by Borrman and the first case of secondary AS described in 1987 by Body et al., attempts have been made to correlate histological features and patterns of growth with outcome (2,4,5). The overall rarity of the condition has limited assessment of prognostic factors and best therapeutic options. As the diagnosis of early breast cancer increases it is expected that there will be a similar increase in the incidence of secondary AS. This literature review will clarify what is known to date about breast angiosarcoma and the salient features that differ between primary and secondary angiosarcoma. Literature search was conducted using the PubMed database, with search terms “angiosarcoma” and “breast”. Results were limited to English language papers and humans with a result of 532 titles. All 242 papers published within the past 20 years had title and abstract reviewed for relevance to our topic of interest. Additional older studies cited by previous reviews were also examined, and findings are summarized.

Presentation and diagnosis

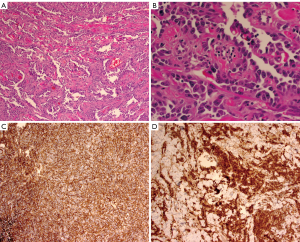

Women with primary AS usually present with a palpable mass, fullness or swelling in the breast, which at times can be rapidly growing. Large masses have been reported leading to platelet sequestration and the hemorrhagic manifestations of Kasabach Merrit syndrome (2,10). Secondary AS, on the other hand, presents as painless bruising that is frequently multifocal but can present with a mass. It is often neglected because of its seemingly innocent appearance (4). There are other varied descriptions of the presenting signs including purplish discoloration, eczematous rash, hematoma-like swelling, and diffuse breast swelling (5) (Figure 1).

Mammogram and ultrasound do not have pathognomonic characteristics in AS which are seen with adenocarcinoma, and nodules, particularly in younger women, these findings may be mistakenly labeled benign. Though there is some evidence that mammographic findings may raise suspicion for this diagnosis (11), multiple studies have demonstrated the ability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to identify patterns of malignancy in AS. AS characteristically results in hyperintensity displayed on T2 images and a rapid initial intense phase followed by washout (12,13). MRI has been demonstrated to be able to detect lesions that were occult to mammography (13).

Diagnosis is often made by FNA or Core Needle Biopsy (CNB) as imaging is often equivocal. Excessive bleeding after FNA or biopsy may be evidence of the presence of this highly vascular tumor (14). In cases of secondary AS, skin punch and incisional biopsy have been recommended (5). On histopathological analysis the lesions are notable for irregular vascular formations evident on with hyperchromatic and irregular nuclei. The diagnosis can be clarified by immunohistologic staining for the endothelial marker CD31, the most sensitive and specific indicator of angiogenic proliferation; however, the lesions will also stain positive for the vascular markers Factor VIII, and Fli1, and will usually at least be weakly positive for CD34 (15-17) (Figure 2).

Metastatic spread of angiosarcoma is thought to be primarily hematogenous; however, isolated case reports of lymphatic spread do exist (18,19). Pulmonary metastasis is the most likely distant site (3,20); however, there are multiple case reports of irregular patterns of metastasis from mammary AS including metastasis to the cecum presenting with GI bleeding (21), lesions developing in the tonsils (22), the buttock (23), the oropharynx (24), and the heart (25).

Surgical treatment

Due to the infrequent incidence of this disease, there are no randomized trials comparing wide local excision or a breast conserving approach with mastectomy. Breast conserving therapy has been utilized but is only recommended for small lesions if there is an excellent chance of achieving negative margins. Total mastectomy alone or with axillary node dissection is the preferred surgical treatment. The necessity for axillary nodal dissection is unclear at present as nodal metastasis is not common in AS. In a review of 280 patients with primary angiosarcomas from ten studies, 75% underwent mastectomy, 25% underwent breast conservation and 42% underwent axillary node dissection in combination with one of the previously mentioned breast procedures. Of those studies that reported nodal involvement, this was present in less than 10% of patients (2).

In one of the largest series of secondary AS focused on surgical treatment, 31 of 35 patients underwent surgery (4). Four patients did not undergo surgery because of metastases or locally advanced disease. Mastectomy was performed in 24 patients and 7 local excisions (some patients had previous mastectomy). Though they determined that mastectomy was more likely to result in an R0 resection (defined in this study as a margin of >2 cm), 14 of the 23 patients with an R0 resection developed local recurrence within six months. In another series the deep margin was the most commonly positive in an incomplete excision suggesting that more aggressive excisions including muscle may be warranted. Many patients in these series required consultation with a plastic surgeon for flap reconstruction (4,5).

Adjuvant treatment

Previous knowledge of treatment for soft tissue sarcomas in general has been applied to AS. The estimated risk of metastases for soft tissue sarcoma has been estimated to be as high as 50%. Some studies suggest that treatment with anthracycline-based chemotherapy can improve both disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) (8). A meta-analysis of patients treated with doxorubicin and a randomized trial of epirubicin plus ifosfamide demonstrated longer DFS and OS (26,27). The rate of delivery of chemotherapy can range from 0% to 65% and selection bias of treating more high risk or high grade patients cannot be ruled out (8). In at least two studies, adjuvant chemotherapy had no effect on recurrence free survival or OS (28,29). Taxane based regimens are also gaining prominence in the treatment of angiosarcoma, with a retrospective analysis of 41 patients, published in 2011 among patients with metastatic angiosarcomas from different primary tumor sites demonstrating an improvement in OS from 10.4 to 23.7 months with taxane based regimens compared to non-taxane based adjuvant chemotherapy (30).

Radiation treatment has been used in the adjuvant setting of breast sarcoma with the intent of improving both locoregional control after surgical excision and survival. In one review of ten series of patients with angiosarcomas of the breast 35% underwent adjuvant radiotherapy (8). Treatment was based on tumor characteristics and the type of surgical treatment (28). Even after mastectomy, radiotherapy has been thought to be beneficial for patient with microscopically positive margins (31). In one series of 14 out of 63 patients treated with radiation either alone or in combination with chemotherapy, there was no correlation to local control or survival (28). In two series, a benefit to the 5 and 10 year recurrence free survival, DFS and OS was seen following radiotherapy (29,32). While there has been suggestion that adjuvant radiotherapy may benefit selected patients, the majority of the data has been based on small retrospective studies that have failed to draw strong conclusions. Utilization of radiotherapy may be limited in many cases of secondary AS, as the breast tissue has already received the maximum dose of radiotherapy (4).

Likewise, the interpretation of the results of adjuvant therapy in secondary AS is limited by the number of cases and the mixed study populations. In a series of 95 patients retrospectively reviewed, adjuvant chemotherapy was found to significantly lower the local recurrence rate; however, did not affect distant recurrence or OS (3). There are few investigations and case reports that have examined the use of (neo)adjuvant paclitaxel, docetaxel, adjuvant vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors, and hyperfractionated radiotherapy. These therapies show promise but need further examination (1,33-37). Imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor has also been suggested as a beneficial treatment in radiation-induced sarcoma (38).

Prognostic factors

Like other sarcomas, tumor size and grade, and margin status in relation to prognosis have been of interest. Trends among series indicate higher rates of local failure with positive margin and higher grade. In one series the authors note an improved DFS for grade I and II tumors compared to grade III (39). Other authors have found similar results with significantly improved DFS and OS in low and intermediate grade tumors compared to high grade tumors (28,40). However in one series of 49 patients with primary angiosarcoma of the breast, analysis demonstrated no correlation between grade and survival (41).

Margin status has also been an important influence of local failure that has been examined in several small series. Multiple authors note that recurrences are more common in those patients with positive or close margins, which at times is in spite of radiotherapy (5,39,42,43).

Studies have demonstrated mixed results in regards to size. Some authors have found that larger size is a negative prognostic factor (3,42,44). Others report that there is no correlation between size and grade or outcome (28,29,39,45).

Prognosis of secondary AS is poor. In a retrospective series of 14 patients over 12 years, incomplete excision was associated with a shorter latency to local recurrence and poor survival. The local recurrence rate was 92% and the median survival time for patients who underwent complete and incomplete excision was 42 and 6 months respectively (5). In one series of 31 patients, in spite of R0 resection, 2/3 developed a local recurrence and median disease specific survival was 37 months (4). In one of the largest series of 33 patients with secondary AS, age greater than 70 and presentation with ecchymosis or violaceous skin were negative predictors of RFS and OS (6). The median survival range reported from seven series is from 15.5-72 months (1). The overall five year survival in various institutional series of primary and secondary AS is 40-55% and 43-88% respectively (1,6).

Summary

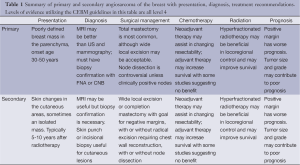

Angiosarcoma of the breast in all presentations is rare. The primary and secondary forms are clinically distinct entities (Table 1). The median age of primary AS in most series is near 40, 30 years younger than that of secondary AS. The lesions of primary AS usually arise in the parenchyma of non-irradiated breast as opposed to those of secondary AS which arise in the dermal and subcutaneous layers of the skin of radiated fields, 7-10 years post radiation and may not necessarily involve the parenchyma. As the use of breast conservation therapy has increased over the last 30 years, it is assumed that the incidence of secondary AS will likely increase and that a judicious approach to delivery of adjuvant radiotherapy in the treatment of breast cancer should be considered.

Full table

The clinical presentation of AS is varied and its sometimes harmless appearance may contribute to a delay and neglect by both patients and physicians. New breast lesions with or without a history of radiation should be evaluated and biopsied for a diagnosis.

As there is no high level evidence on which to base recommendations, no clear consensus exists on the surgical management of AS of the breast. In most series that discuss procedures, the majority of primary AS patients undergo mastectomy. The management of secondary AS is less clear, as these patients have already undergone surgical management for their original breast cancer. Wide local excision is often reported, but whether or not all irradiated skin is removed is not specified. Furthermore, because the deep margin has been the typical site of margin positivity, the depth of the resection is controversial. Some authors have recommended aggressive resection including removal of muscle (5,6).

It is clear that aggressive treatment of AS of the breast is necessary; however, the role of neoadjuvant, and adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy remains ill-defined. Referral to a specialized center with multidisciplinary care, including plastic surgeons, medical, radiation and surgical oncologists is important to enhance the complicated decision making and to allow for the multimodality therapies necessary in the treatment of this aggressive malignancy.

Acknowledgements

Kazuaki Takabe is funded by United States National Institute of Health (R01CA160688) and Susan G. Komen Foundation (Investigator Initiated Research Grant (IIR12222224). Krista Terracina is supported by National Institute of Health (T32CA085159-10).

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hui A, Henderson M, Speakman D, et al. Angiosarcoma of the breast: a difficult surgical challenge. Breast 2012;21:584-9. [PubMed]

- Kaklamanos IG, Birbas K, Syrigos KN, et al. Breast angiosarcoma that is not related to radiation exposure: a comprehensive review of the literature. Surg Today 2011;41:163-8. [PubMed]

- Torres KE, Ravi V, Kin K, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with radiation-associated angiosarcomas of the breast following surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:1267-74. [PubMed]

- Seinen JM, Styring E, Verstappen V, et al. Radiation-associated angiosarcoma after breast cancer: high recurrence rate and poor survival despite surgical treatment with R0 resection. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:2700-6. [PubMed]

- Jallali N, James S, Searle A, et al. Surgical management of radiation-induced angiosarcoma after breast conservation therapy. Am J Surg 2012;203:156-61. [PubMed]

- Morgan EA, Kozono DE, Wang Q, et al. Cutaneous radiation-associated angiosarcoma of the breast: poor prognosis in a rare secondary malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:3801-8. [PubMed]

- Billings SD, McKenney JK, Folpe AL, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma following breast-conserving surgery and radiation: an analysis of 27 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:781-8. [PubMed]

- Fodor J, Orosz Z, Szabó E, et al. Angiosarcoma after conservation treatment for breast carcinoma: our experience and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:499-504. [PubMed]

- Roy P, Clark MA, Thomas JM. Stewart-Treves syndrome--treatment and outcome in six patients from a single centre. Eur J Surg Oncol 2004;30:982-6. [PubMed]

- Bernathova M, Jaschke W, Pechlahner C, et al. Primary angiosarcoma of the breast associated Kasabach-Merritt syndrome during pregnancy. Breast 2006;15:255-8. [PubMed]

- Moore A, Hendon A, Hester M, et al. Secondary angiosarcoma of the breast: can imaging findings aid in the diagnosis? Breast J 2008;14:293-8. [PubMed]

- Sanders LM, Groves AC, Schaefer S. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the breast on MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187:W143-6. [PubMed]

- Yang WT, Hennessy BT, Dryden MJ, et al. Mammary angiosarcomas: imaging findings in 24 patients. Radiology 2007;242:725-34. [PubMed]

- Assalia A, Schein M. Severe haemorrhagic complication following needle or open biopsy of a breast mass: suspect angiosarcoma. Br J Surg 1992;79:469. [PubMed]

- Hart J, Mandavilli S. Epithelioid angiosarcoma: a brief diagnostic review and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2011;135:268-72. [PubMed]

- Folpe AL, Chand EM, Goldblum JR, et al. Expression of Fli-1, a nuclear transcription factor, distinguishes vascular neoplasms from potential mimics. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1061-6. [PubMed]

- Bennani A, Chbani L, Lamchahab M, et al. Primary angiosarcoma of the breast: a case report. Diagn Pathol 2013;8:66. [PubMed]

- Carter E, Ulusaraç O, Dyess DL. Axillary lymph node involvement in primary epithelioid angiosarcoma of the breast. Breast J 2005;11:219-20. [PubMed]

- Losanoff JE, Jaber S, Esuba M, et al. Primary angiosarcoma of the breast: do enlarged axillary nodes matter? Breast J 2006;12:371-4. [PubMed]

- Nicolas MM, Nayar R, Yeldandi A, et al. Pulmonary metastasis of a postradiation breast epithelioid angiosarcoma mimicking adenocarcinoma. A case report. Acta Cytol 2006;50:672-6. [PubMed]

- Allison KH, Yoder BJ, Bronner MP, et al. Angiosarcoma involving the gastrointestinal tract: a series of primary and metastatic cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:298-307. [PubMed]

- Bar R, Netzer A, Ostrovsky D, et al. Abrupt tonsillar hemorrhage from a metastatic hemangiosarcoma of the breast: case report and literature review. Ear Nose Throat J 2011;90:116-20. [PubMed]

- Baum JK, Levine AJ, Ingold JA. Angiosarcoma of the breast with report of unusual site of first metastasis. J Surg Oncol 1990;43:125-30. [PubMed]

- Chiarelli A, Boccone P, Goia F, et al. Gingival metastasis of a radiotherapy-induced breast angiosarcoma: diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment achieving a prolonged complete remission. Anticancer Drugs 2012;23:1112-7. [PubMed]

- Kim EK, Park IS, Sohn BS, et al. Angiosarcomas of the bilateral breast and heart: which one is the primary site? Korean J Intern Med 2012;27:224-8. [PubMed]

- Pervaiz N, Colterjohn N, Farrokhyar F, et al. A systematic meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of adjuvant chemotherapy for localized resectable soft-tissue sarcoma. Cancer 2008;113:573-81. [PubMed]

- Frustaci S, Gherlinzoni F, De Paoli A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for adult soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities and girdles: results of the Italian randomized cooperative trial. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:1238-47. [PubMed]

- Rosen PP, Kimmel M, Ernsberger D. Mammary angiosarcoma. The prognostic significance of tumor differentiation. Cancer 1988;62:2145-51. [PubMed]

- Sher T, Hennessy BT, Valero V, et al. Primary angiosarcomas of the breast. Cancer 2007;110:173-8. [PubMed]

- Hirata T, Yonemori K, Ando M, et al. Efficacy of taxane regimens in patients with metastatic angiosarcoma. Eur J Dermatol 2011;21:539-45. [PubMed]

- McGowan TS, Cummings BJ, O’Sullivan B, et al. An analysis of 78 breast sarcoma patients without distant metastases at presentation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;46:383-90. [PubMed]

- Johnstone PA, Pierce LJ, Merino MJ, et al. Primary soft tissue sarcomas of the breast: local-regional control with post-operative radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1993;27:671-5. [PubMed]

- Palta M, Morris CG, Grobmyer SR, et al. Angiosarcoma after breast-conserving therapy: long-term outcomes with hyperfractionated radiotherapy. Cancer 2010;116:1872-8. [PubMed]

- Penel N, Bui BN, Bay JO, et al. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel for unresectable angiosarcoma: the ANGIOTAX Study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5269-74. [PubMed]

- Nagano T, Yamada Y, Ikeda T, et al. Docetaxel: a therapeutic option in the treatment of cutaneous angiosarcoma: report of 9 patients. Cancer 2007;110:648-51. [PubMed]

- Park JW, Serafica-Karen C, Das K. Fine-needle aspiration of metastatic radiation-induced cutaneous epithelioid angiosarcoma of the breast to the liver: A diagnostic dilemma. Diagn Cytopathol 2010;38:768-71. [PubMed]

- Scott MT, Portnow LH, Morris CG, et al. Radiation therapy for angiosarcoma: the 35-year University of Florida experience. Am J Clin Oncol 2013;36:174-80. [PubMed]

- Komdeur R, Hoekstra HJ, Molenaar WM, et al. Clinicopathologic assessment of postradiation sarcomas: KIT as a potential treatment target. Clin Cancer Res 2003;9:2926-32. [PubMed]

- Bousquet G, Confavreux C, Magné N, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in breast sarcoma: a multicenter study from the rare cancer network. Radiother Oncol 2007;85:355-61. [PubMed]

- Luini A, Gatti G, Diaz J, et al. Angiosarcoma of the breast: the experience of the European Institute of Oncology and a review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007;105:81-5. [PubMed]

- Nascimento AF, Raut CP, Fletcher CD. Primary angiosarcoma of the breast: clinicopathologic analysis of 49 cases, suggesting that grade is not prognostic. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1896-904. [PubMed]

- Adem C, Reynolds C, Ingle JN, et al. Primary breast sarcoma: clinicopathologic series from the Mayo Clinic and review of the literature. Br J Cancer 2004;91:237-41. [PubMed]

- Barrow BJ, Janjan NA, Gutman H, et al. Role of radiotherapy in sarcoma of the breast--a retrospective review of the M.D. Anderson experience. Radiother Oncol 1999;52:173-8. [PubMed]

- Zelek L, Llombart-Cussac A, Terrier P, et al. Prognostic factors in primary breast sarcomas: a series of patients with long-term follow-up. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2583-8. [PubMed]

- Blanchard DK, Reynolds CA, Grant CS, et al. Primary nonphylloides breast sarcomas. Am J Surg 2003;186:359-61. [PubMed]